Kyoto

For our 2023 issue: TLmag39: The Culture of the Object, Danielle Demetriou wrote about the timeless history of Kyoto, its culture passed down for over 1,200 years, and contemporary brands and creatives who continue the traditions.

My first ever footsteps in Kyoto traced a line through a temple of glass and steel. Arriving at the train station, I wandered beneath a symphony of industrial curves and light refractions cutting sharply into skies. The dynamism of form was mirrored in its internal humming: the waxing and waning of white-nosed bullet trains – arriving, departing – and a river-like flow of humans along escalators and walkways.

Kyoto. The name of this city often brings to mind time-halting images of all things ancient – the Zen gardens, the old machiya townhouses, the bamboo whisk of forest green matcha, the crafted tools, the light-muting paper screens, the constellation of Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines (an estimated 2,000 in total).

The city is all these things. It’s wrapped in a circle of mountains, where countless stories – of battles, gods, tea rituals, loves, enlightenment – are written into its peaks, rocks, rivers, trees and moss. Inside this cocoon sits Kyoto, a small but perfectly formed urban time capsule of traditional culture, the paper-thin layers of its heritage a legacy of more than millennia as Japan’s ancient capital. Yet, Kyoto is not just about the past. This is clear from the first sight that greets many new visitors (myself included, nearly 20 years ago): the train station. Completed by architect Hiroshi Hara in 1997 – to mark the 1,200th anniversary of the city’s founding – Kyoto Station is one of Japan’s biggest buildings, a 15-storey high industrial metaphor of a “geographic valley”, an ultra-modern web of arcs, lines, light.

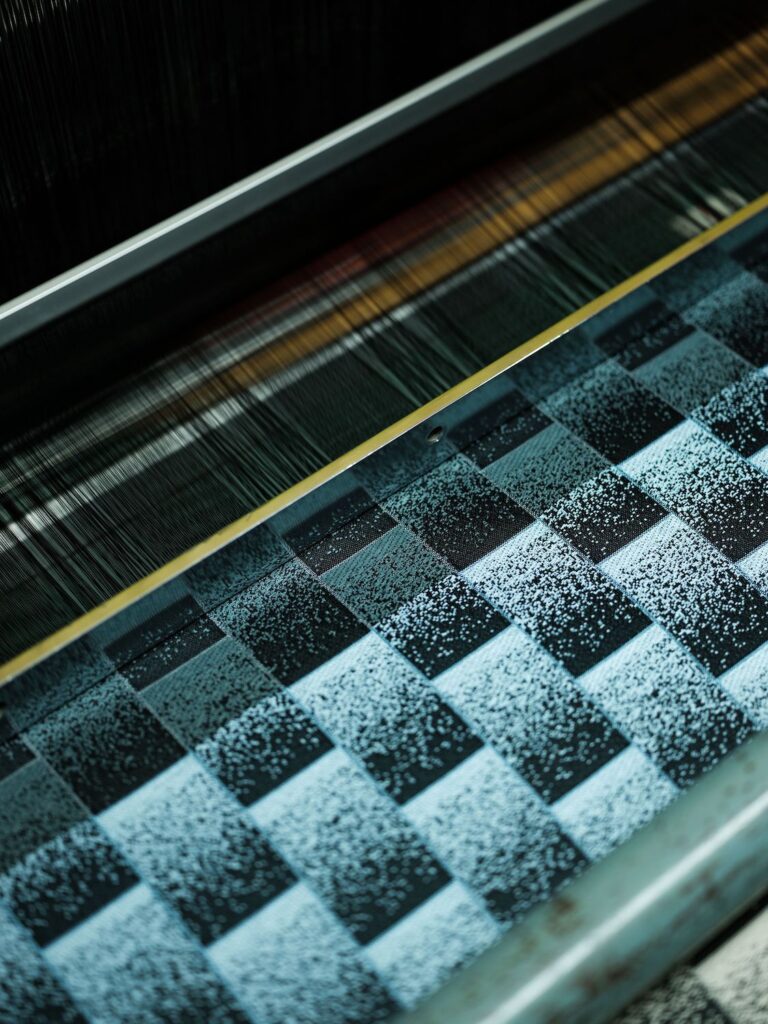

The fact that the gateway to Kyoto is so contemporary offers a telling insight into the complexity of its self-identity. Kyoto has long hovered somewhere at the sweet spot between steel and clay, modern and mythical, technology and poetry, future and past – with its essence ultimately defined by innovation. This spirit of innovation has not only fuelled Kyoto Station and a thriving tech industry (Kyoto is famously the birthplace of Nintendo); it’s also kept alive by centuries-old artisan families and its rich web of cultural traditions and craftsmanship techniques, with each new generation head having to embrace the challenge of stepping into the future, by experimenting and innovating in order to survive.

My own Kyoto journey is entwined with its many stories, old and new. For around 15 years, while living in Tokyo, I visited the city to write about people and spaces, ideas and objects, interviewing a rich cast of Kyoto characters – tea masters, monks, farmers, Buddha sculptors, potters, paper makers, scientists, chefs, artists.

As I began untangling the golden threads of Kyoto’s DNA, the poetry of the city gradually shifted into light-flooding focus, sparking curiosity and inspiration in equal measure – until eventually, Kyoto’s siren’s call began to drown out the soundtrack of Tokyo, my long-time home.

Last year, a new chapter began after swapping the white modernity of our apartment in Tokyo for the soft tones, natural textures and light-and-shadow dances of an old machiya house in Nishijin, Kyoto’s old kimono textile district.

Today, my eyes have slowly adjusted to a Kyoto sensibility (dark woods, aromatic tatami, paper screens, tsuchi-kabe earthen walls). Hand in hand with this is a heightened sensitivity to light and shadows – from the shafts of sunlight that hit the kitchen from the skylights at midday to the playful shadows and muted reflections on paper screens after dark.

Life has a new tempo and a deeper connection to nature, through the mountains I see cycling home, at the end of almost every street; to the seasonal shifts in our small Japanese garden; as well as the objects that surround us. Objects in Kyoto typically contain layers of history and countless stories – be it an antique tea bowl, imprinted with the hands of an unknown artisan; a small piece of wood from an ancient Buddha statue that once sat in a Kyoto temple, which I found in my neighbour’s antique shop; or sencha tea leaves farmed in the surrounding mountains.

Kyoto’s cornucopia of objects often possess a singular beauty imbued with a sense of the spiritual – a likely consequence of countless elements of its traditional culture being rooted in Zen Buddhism.

One person who perhaps best understands the complexity of Kyoto’s identity – and its balancing act between past and future – is Masataka Hosoo. The gently spoken head of the 16th century traditional kimono company Hosoo, is as comfortable deep diving into explorations of natural dyeing materials and traditional loom techniques as he is creating a tapestry inspired by David Lynch, an exhibition for the Milan Salone, handbags for Gucci or textiles for guest rooms at the shiny new Bulgari Hotel Tokyo.

For Masataka – modest, unassuming and avant-garde, often dressed with impeccable understated style in dark toned kimono – Kyoto can perhaps be summed up in three words: “Creativity, challenge and innovation”. He adds: “Throughout Kyoto’s 1,200-year history, various cultural elements from different eras have been continuously passed down. There is also the passion and creativity of contemporary individuals. Moreover, the city’s size is on a human scale, promoting creative interactions between people.”

Then there is Kyoto’s singular culture of the object. From tea whisks and ceramic cups to paper lanterns – objects handcrafted in Kyoto are often archaeological records of the city’s ever-evolving identity. Written into their curves, lines and surface textures is the wisdom of the city’s history and heritage, craftsmanship and creativity.

“Beautiful objects transcend human lifespans and are passed down,” explains Masataka, who identifies his own favourite Kyoto object as naturally-dyed silk Hosoo pyjamas. “We can interpret the aesthetic sensibilities of our ancestors from these objects. Items that have been created and passed down throughout Kyoto’s 1,200-year history possess a timeless power, and we can learn something essential and valuable from them.” It’s perhaps little surprise that the city remains today something of a mecca for creatives – as reflected by Mami and Ryo Suzuki, the artistic couple behind Kankakari, a new gallery space in the Nishijin district. The discovery of a 97-year-old traditional house on a quiet street sparked an immediate catalyst for change. The house was “leaning, with signs of termite damage and most walls in a state of disrepair,” according to Ryo – yet they instantly fell in love with it.

At the time, they were living in Hiroshima, running a shop and gallery. The house, however, led them in a new direction. An 18-month passion project followed, as they designed its resurrection, working alongside a specialist contractor to restore the house to its former glory, using as many traditional techniques as possible. In June last year, the pair moved in – immersing themselves in an escapist haven of wood, earth and stone. The sensitively restored house, the former residence of a grain merchant, balances a deeply serene atmosphere with its tactile natural textures, from the large genkan entranceway and solid timberwork to its courtyard garden.

In addition to making it home, the space also showcases regular exhibitions – from basket weaving and ceramics to woodworks. A recent highlight includes he poetic nature-edged lines of woodworks crafted by Yoshinori Yano. And the thread connecting everything today is a respect for the “spirituality” of the object. “Kankakari is a place that serves as both a gallery and a home,” explains Ryo. “In this space, we exhibit handcrafted works that inspire us, regardless of the framework of craft and art. What matters most is not novelty or beauty, but rather the “spirituality” under- lying the object itself. This spirituality can sometimes reside within the artist themselves, and at other times, it can be found within the process of creation, the materials, or the form.

“We believe that everyday items, from vessels to clothing that touches the skin, from decorations to a home as a living space, are all extensions of one’s own body. It is important that they harmonise, providing a seamless and comfortable experience.”

Citing both tea ceremony tools and teahouse-style sukiya architecture as examples, he adds “These show the accumulation of history and culture in a very detailed manner. We feel the elegance of a culture of extreme maturity.” And it’s this culture that defines the spirit of Kyoto, a city whose objects combine to create a cityscape of beauty and wisdom, inspiration and innovation – from its crafted tea ceremony tools to its train stations.

www.hosoo.co.jp

@hosoo_official

@kankakari