Stephen Burks on A/D/O Residency

Zachary Sachs interviews Stephen Burks about his collaborative craft-based approach to industrial design, which can be seen in his A/D/O exhibition extended until June 11.

The exhibition showing the results of Stephen Burks’ four-month residency at A/D/O in New York has been extended until June 11. Burks is the first designer-in-residence at the Brooklyn-based creative space, which endeavours to provoke professional designers to expand the boundaries of design. Zachary Sachs interviewed him for the A/D/O Journal about his practice and process, and how design navigates both production processes and cultures.

Himself a New York resident, Burks has over a decade of experience bridging craft traditions, manufacturing and contemporary design. He has consulted for furniture manufacturers Cappellini, Missoni, Dedon and Ligne Roset to create luxury objects that fuse material innovation with handcraft techniques. A recipient of the Cooper Hewitt National Design Award for industrial design, he’s the first designer to have a solo show at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Burks’ approach reconsiders the role of craft in manufacturing.

Zachary Sachs: Can you describe your schooling and background? Where you’re from and what attracted you to industrial design in the beginning?

Stephen Burks: I’m from Chicago and studied product design at the Illinois Institute of Technology’s Institute of Design – the New Bauhaus – and architecture at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture. I discovered design through my interest in architecture and the Bauhaus before university. I’ve always been interested in the scale of the hand and the body in the interior, as opposed to the building in the landscape.

How did you come to focus on handcraft? Was it a sudden realisation based on a project or more gradual?

Up until we made our first handcrafted objects for Missoni over 10 years ago, I had been practicing internationally working in a fairly traditional way as a design consultant collaborating with global brands. The realisation of what I could do by hand came when I saw the success of our Missoni Patchwork Vases and the improvisational nature of making things in Africa on my first product development trip for Aid To Artisans. After working in South Africa, Colombia, India, Senegal, Rwanda, Kenya, Ghana, Indonesia, the Philippines and Haiti, as well as Italy, France, Germany, Spain, the UK and the US, I’m convinced that we are all capable of design and it is design that will eventually bridge the gap between cultures, moving us all into the 21st century through a combined technological intelligence of what can be done best by hand and what can be done by industry.

Was there one project you most associate with this evolution in your practice?

The Missoni Patchwork Vases, which are made from recycled cut-offs of computer-loomed fashion fabrics patchworked by hand on to industrial vases!

There seems to be an emphasis on traditions of both craft and modes of production on a global scale. How do you find design, production and the relationship to objects varies by location and culture? What are some things you learned or observations that arose from contrasting these modes?

We have all existed on Earth for thousands of years in various stages of development simultaneously. No one culture has the right to consider itself more ‘advanced’ than another nor dictate taste or style. In all my travels, I’ve found that Design is a Western concept. In the rest of the world, people manipulate material to their advantage and make beautiful things every day without any education in Design, as we know it. Ideas evolve and find their way into products through necessity, and invention or innovation is really not a question of limited systems, but of wisdom and shared know-how. I believe that technology is the future of craft and the wisdom of so many shared peoples, from the French ateliers of haute couture to the potters wheel of Peru both have something in common and something to share with the most advanced factories and our digital lives, in general. In fact, even in Italy most of the international design brands began from family traditions of making that were passed down and eventually industrialised. The same will eventually be true in the rest of the world, with the right investment, but the wisdom of these cultures shouldn’t be lost. Our work is about extending these craft traditions into the future through the appropriate application of this accumulated wisdom to make great products, regardless of whether or not we’re in the factory or the village.

How does craft relate to mass-production? How does this intersection inform your approach to a specific product?

Hand production is the basis of mass production. All mass production developed from the limits of hand techniques. It’s this know-how that we try to bring to every project, even the industrial ones. We believe the closer the hand gets to the act of making, the more potential there is for innovation, even if, ultimately, the product isn’t made by hand. What we call craft, is our original way of expressing our understanding of the physical world. We believe it is this understanding that will inform the most expressive intelligent technically produced products in the future.

What are you working on right now?

We’re always working on a large variety of products simultaneously including client-based research and development of home accessories, lighting, seating and textiles. In parallel, we constantly try to develop self-initiated projects that propel us forward. After our residency at A/D/O, our research into the intersection between technology and craft continues.

Maybe walk us through the origination process for one of these projects, from the initial idea to the iterations, to the development of the fabrication approach, to the marketing etc?

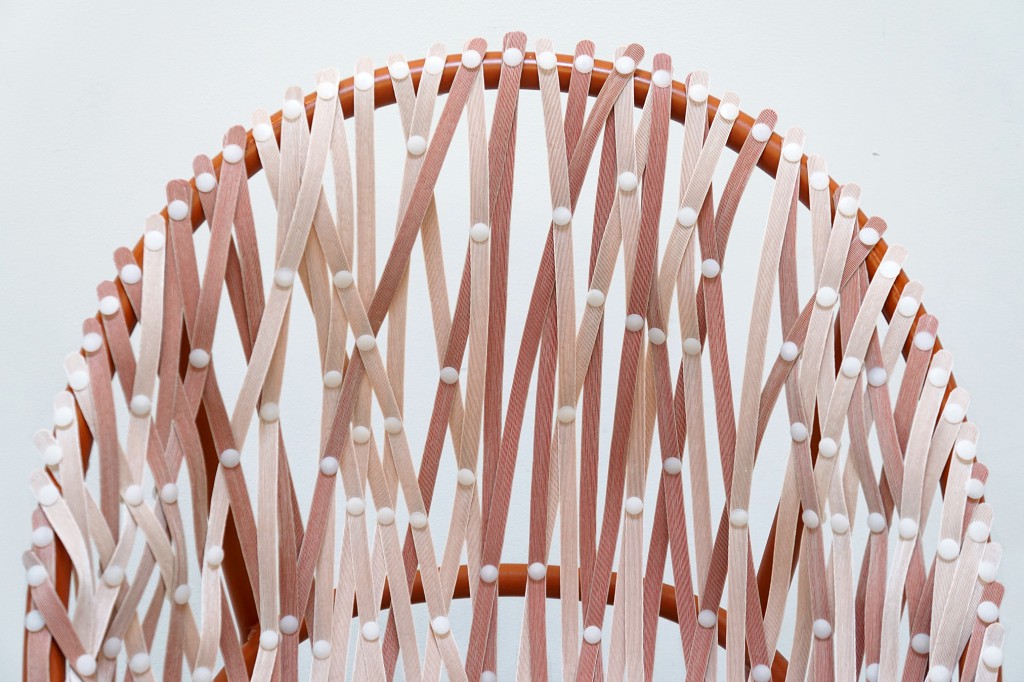

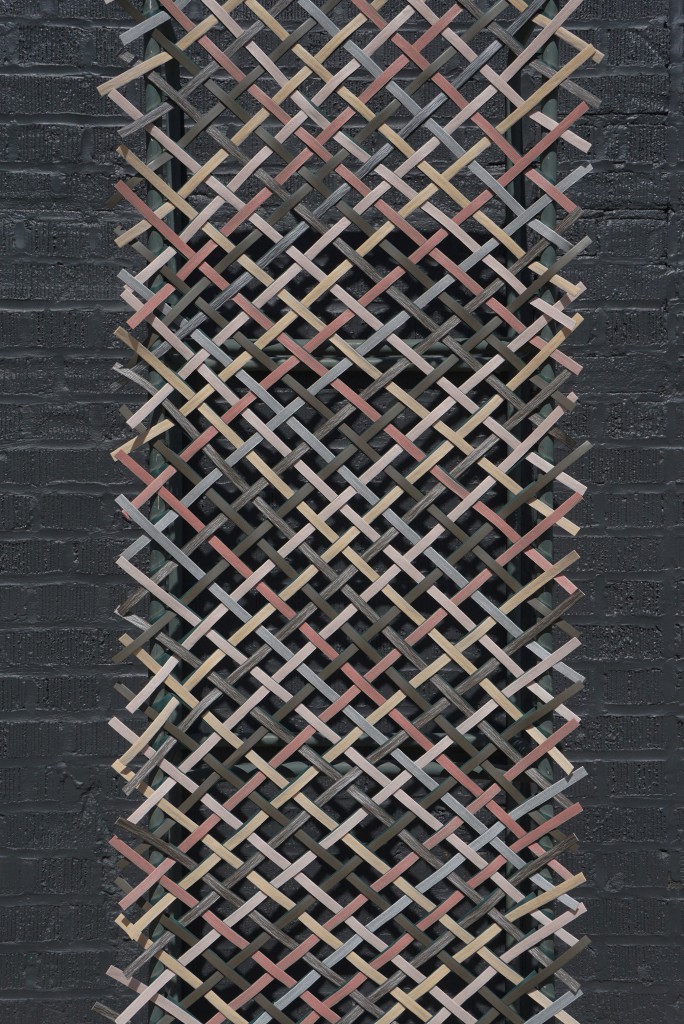

For our Dedon Irregular Weaving project, for example, we began with a simple idea that we felt could inform a new direction in woven outdoor furniture. Could the artisan participate more creatively in the production of more unique pieces of furniture that take full advantage of the fact that they are made by hand? Dedon felt this was worth exploring and supported our residency here at A/D/O with resources, raw material and expertise, which began as a series of 2D/3D sketches and took the form last month of an Irregular Weaving workshop here at A/D/O. In tandem with more sketches, study models and full-scale prototypes, we took the results of the workshop and applied our learnings to the work in progress. Now, we’re fully immersed in continuing to explore the possibilities of what Irregular Weaving can bring to Dedon’s manufacturing culture. If this advanced research work, in fact, now becomes a ‘real’ project for Dedon, our workshop-based practice will take us to both Germany and the Philippines to work closely with their in-house R&D teams to find patentable industrial and manual ways of innovating even further through working prototypes and final production models over the next year or two.

Originally published on the A/D/O Journal.