Studio Ossidiana: Back to the Future

For our A/W 2022 issue: TLmag38:Origins, Adrian Madlener spoke with Alessandra Covini and Giovanni Bellotti of the award winning architecture, design and research practice Studio Ossidiana.

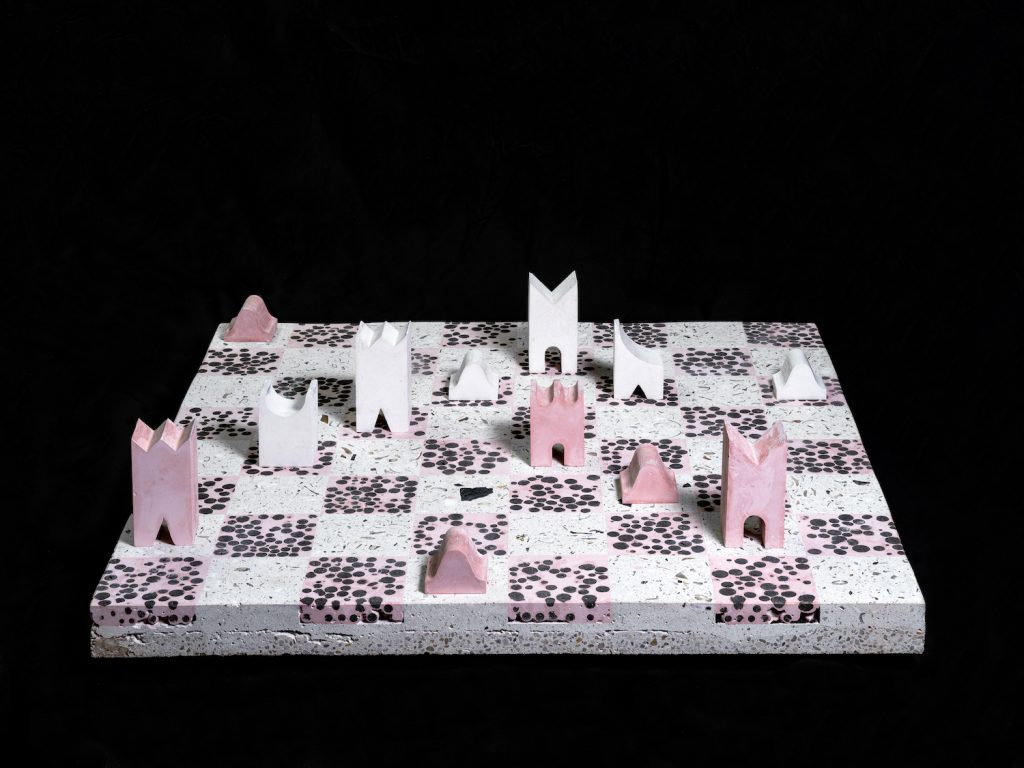

Established in 2015, Rotterdam-based architecture and design practice Studio Ossidiana continuously develops projects that address today’s most pressing issues. Whether a spatial installation — Civic Roofscapes — dwellings for sentient beings other than humans — Pigeon Tower — or the reprogramming of parks through the introduction of simple yet effective equipment — Utomhusverket — the architect-trained pair tries to introduce instigations that are at once playful and thought-provoking. Incorporating a sense of tactility and inclusivity, Studio Ossidiana’s proposed spatial reconfigurations — Three Floating Rooms at Kunstpaviljoen in Flevoland, The Netherlands — and standalone objects — The Fire Dune — are meant to inspire wonder. Ultimately, that curiosity should be effectuated into action. The award-winning duo, comprised of Alessandra Covini and Giovanni Bellotti, firmly believes that understanding history and age-old practices are essential to tackling the seeming unsurmountable challenges of the present. However nuanced or revolutionary, innovation doesn’t exist in a bubble or emerge out of thin air. Precedence is critical to formulating any substantial and sustainable solution, even if just speculative. Working with this foundation isn’t limited to a reverence for old masters and ancient cultures but can also stem from one’s process, pulling from past research to inform current investigations.

TLmag: How is tapping into historical procedures central to your world?

Alessandra Covini: Looking at a shelf of material samples in our studio, I’m struck by the number of material samples we’ve produced in the past few years. Some were the starting point of a project, others a result, but most often, they were part of a cycle of reinvention in which materials developed for a project in Almere, The Netherlands, have found new meanings in Venice, Istanbul, and Stockholm. I wonder how they situate in time. Many of them were made with shells, the exoskeleton of what was a living animal. Some of these shells are thousands of years old and were taken from the sea bed as a by-product of sand extraction. Some were attached to their molluscs just a few weeks ago, like the oysters we kept from a recent dinner with friends. Tiles were made from a living being which became a mineral, then composed into a new “man- made” stone used as flooring or for a facade of a building that will hopefully exist longer than ourselves. And that same material will likely become matter again, perhaps the ingredient of a terrazzo composite. It reminds us that everything is somehow eternal and that design, as the late Bruno Latour said, is constantly being “redesigned.” Archaeology is vital to us because it is about the future as much as it is about the past.

TLmag: Why is it so essential to re-evaluate contemporary practices that are harmful or ineffectual?

Giovanni Bellotti: We might be the only animals on earth that reinvent things that already work, often undoing a process to do something different but not necessarily better. Other animals “build,” too, but we can trust that a swallow’s nest or termite’s hive will work in the same way a thousand years from now. Our idea of what is harmful or ineffective keeps changing, and centuries or months from now, we will see forms of violence that we might have never imagined were possible. We like to think that desire, not necessity, should drive us forward. We know we “have to” re-evaluate how we build, travel, and relate to other forms. I think a “better” future can only come if driven by visions for the future, optimism, and a willingness to understand different ways of relating to materials, soils, and animals; rather than guilt about what we’ve lost or fear of the massive changes ahead.

TLmag: What is design and architecture’s role in reintroducing age-old traditions and mindsets when it comes to sourcing material, implementing construction and assembly techniques, engaging an audience, etc.?

A.C.: Current practices that draw from “tradition” are not focused on the revival of the past but rather a challenge to the present. Materials have become central to many practices, whether through projects of reuse; the invention of new composites; or the (re) discovery of the properties of algae, fungi, and hemp. Many of these practices draw from the past. Still, they reflect a very urgent change of values where the externalities of a project — the unaccounted “costs” in terms of labour, sourcing, emissions, etc. become the main subject of the work. In this sense, architecture and design can perhaps expand their agency, stretching before and beyond the conventional boundaries of a project when confined between the client and the builder. These new boundaries don’t just raise the scope of a designer’s work but also its meaning, embracing the possibility of telling a story through the very matter of a project itself.

@studio_ossidiana