Abwab: Opening Doors for MENASA Designers

At this year’s Dubai Design Week, the Abwab exhibition showcased the work of more than 40 regional designers who use objects to blend the past and present of their countries

“Jaba’ is more used to industrial glassmaking, so this was a challenge,” explained Palestinian architect Dima Srouji, pointing at the stuff of Murano’s id. Her joyful Hollow Forms collection was the result of a mix between her 3D design skills and the collected seven-century know-how of glass artisans in the West Bank village. “The aim is to look back to move forward [and] produce objects that will resonate with a sense of place, while maintaining the ability to act on a regional and global level.”

That is also, in a way, the aim of Abwab, an exhibition born alongside the Dubai Design Week. Its third edition, which took place in mid November, showcased the work of 46 up-and-coming designers from the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia, with pieces ordered by common themes —Interpretation, Tactility and Nostalgia, for example— instead of common nationalities.

Abwab is the Arabic word for doors, and fittingly, it aims to open them for young designers hailing from the MENASA region. Judging by the critical success of the show’s two previous iterations, it’s succeeding. “There are very few opportunities for people to tell stories the way that they can here: we’re talking about production techniques, really articulate forms of craftsmanship and machine work, people blending who they are today with who they were in the past,” explained interior architect Rawan Kashkoush, Abwab’s creative director and the show’s curator.

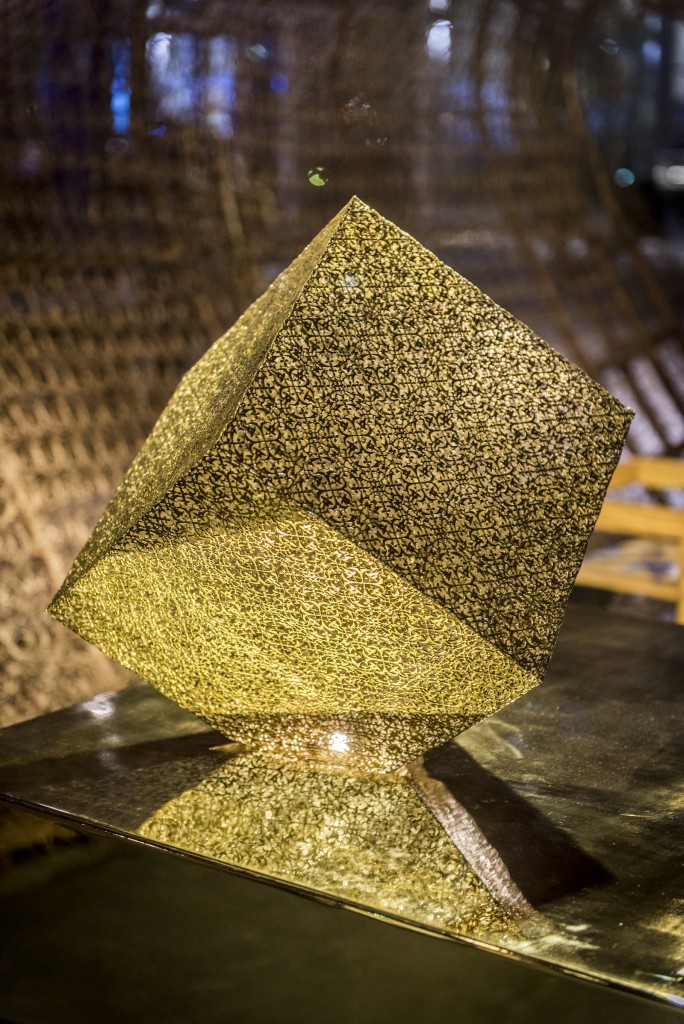

“I think she was talking about us when she said that,” half-joked Mounia Meftah, part of Moroccan duo Maison MEFTAH. Their Unité brass lamp, made with intricate arabesque openwork, is the result of five years of reflection, one and a half years of specialised training and 1,600 hours of dedicated work from a small group of Moroccan goldsmiths. Ilyas Meftah replied to the artisans’ questioning of the feasibility of the design by introducing saws meant for jewellery making, capable of making holes as small as a quarter millilitre wide, even through copper. “[Rawan] told us that this piece deserved the space and time of an exhibition like this one to explain all the hours spent on this bit of chemistry between contemporary design and the ancestral know-how of our artisans,” Kashkoush added.

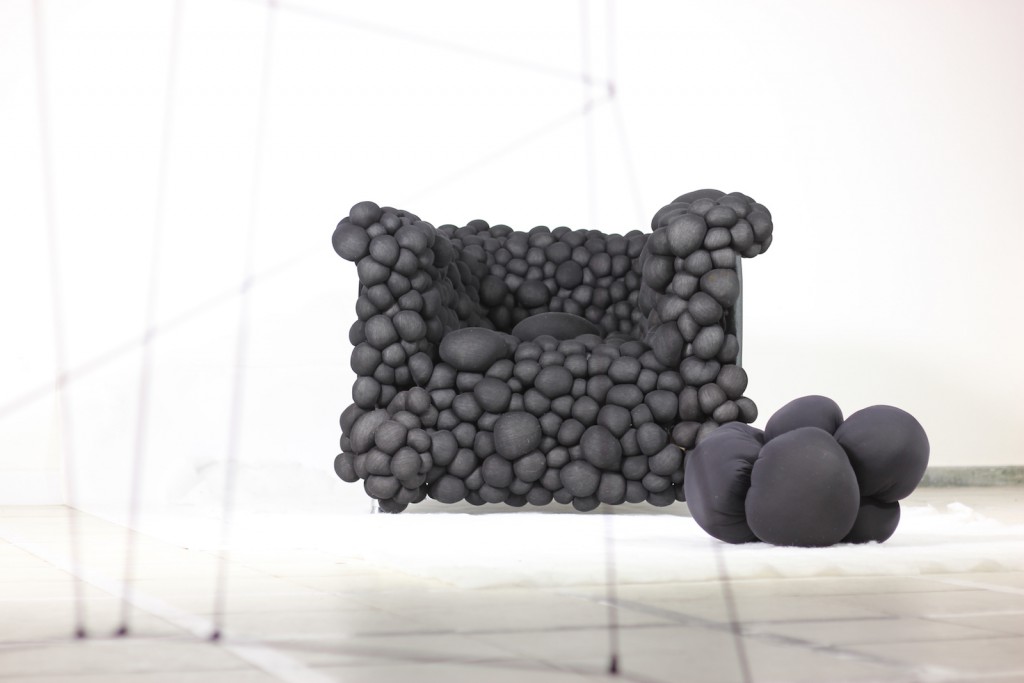

That chemistry —what the curator calls “crazy explosions”— is also present in works like Kawther Al Saffar’s bowls made in conjunction with Kuwaiti craftsmen and Sema Ourouk’s Muquarnas lamp, an interpretation of the traditional Islamic architecture element. This selection is not meant to celebrate collaboration for collaboration’s sake, but instead it questions the region’s current need for cultural and commercial imports. “There’s often an interest to go to the veterans, rather than rely on local groups,” Kashkoush explained. “The Middle East is transitioning in terms of contemporary taste, and there are fewer Middle Eastern designers servicing the way we seat, the way we eat, the tableware we use. We grew a tendency for purchasing these things from farther away, but those designers are now finding that they need to make room for people like us, who can design with our own flavour.”

And therein perhaps lies the biggest value of exhibitions like Abwab: with these proposals, the local scene is fiercely pushing for the room and the visibility to allow the country and the region to create their own contemporary veterans.

See our captions for more information on the pieces and the (striking) main material of the pop-up venue