Constantin Boym on Humour

Russian-born New York-based designer Constantin Boym tells TLmag about cultural mash-ups, design with humor and the power of observation.

Since opening Boym Partners in New York City in 1986, Constantin Boym has been an integral part of the international and New York design worlds, creating work that seems to connect directly with the energy, attitude and diversity of the city. While designing for leading companies including Alessi, Swatch, Flos and Vitra and developing exhibition designs for several American museums, he has also played an important role as a professor and lecturer at New York design schools, most recently assuming the chairmanship of Industrial Design at Pratt Institute. His work has been the subject of two retrospective exhibitions, Oh Boym! and America, and two monographs, Curious Boym: Design Works and Constantin Boym: America. He is also the author of New Russian Design, published by Rizzoli.

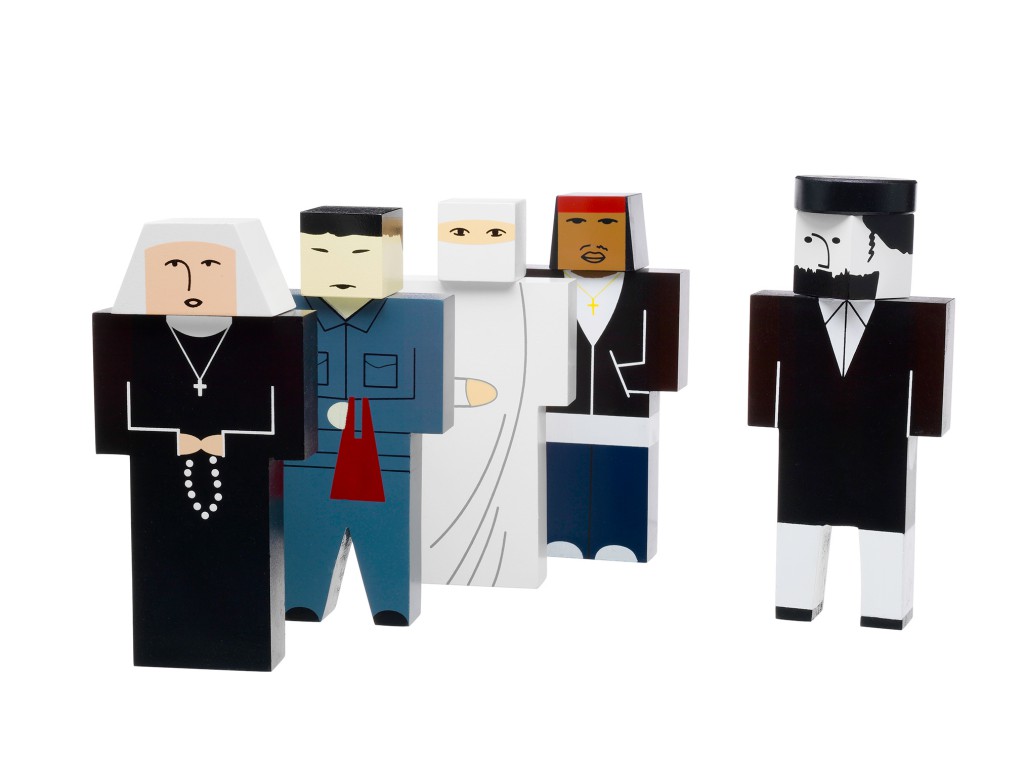

Constantin Boym was born in Moscow, Russia and graduated from the Moscow Architectural Institute. He went on to earn a master’s degree in design from Domus Academy in Milan in 1985, becoming a registered architect in the United States in 1988. In 1995, Laurence Leon Boym joined Boym Partners. Several works by the pair, including the iconic Babel Blocks, belong to the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The two have received numerous awards, including from the I.D. Magazine Annual Design Review, and in 2005, they were finalists for the National Design Award for Product Design.

TLmag: There is something quintessentially New York about your work: its energy, humor, irony and passion. How has the city influenced your work over the years?

Constantin Boym: Our world today is a troubled place. Yet I believe that serious and controversial problems can and should be addressed with a sense of humor. At the outset of modernism in America, Charlie Chaplin introduced comedy as a way to relate to the harsh realities of modern times. In our own generation, Jerry Seinfeld, and later, Louis C.K., made us laugh by pointing out trivial details of everyday human behavior. Much artistic experimentation takes place in what curator Adam Gopnik defined as “the free zone of humor.” New York culture, in particular, has benefited from operating in this fertile territory, using sampling and mashing, borrowing from high and low, embracing irreverence and controversy. The big reason for this vitality has, of course, been the contribution of new immigrants, creative people of different races, religions and national backgrounds, something that is currently under threat.

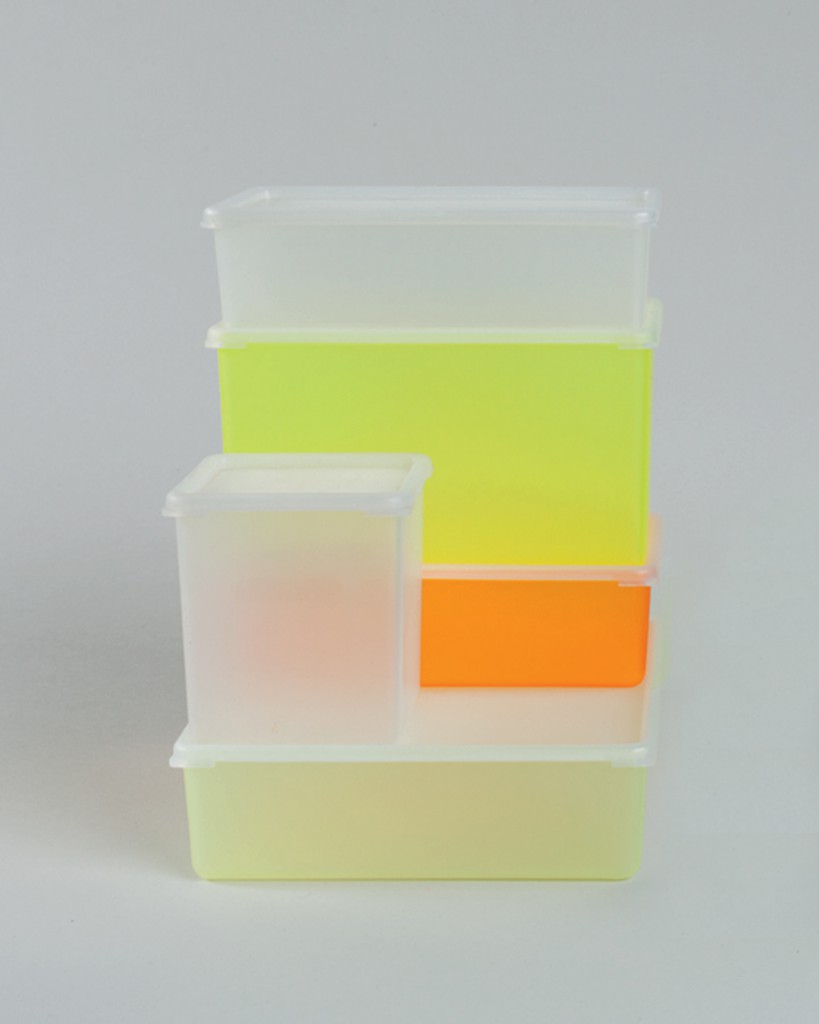

We paid homage to people of New York City in our project Babel Blocks (2008), a new kind of souvenir that celebrated the multicultural diversity of the city streets and neighborhoods. The cultural mutations of this project—it evolved from souvenirs to videos to a recent outdoor public mural—is a testament to how New York continues to inspire our work.

TLmag: You are currently the head of the Industrial Design department at Pratt Institute, and from 1987 to 2000, you were on the faculty of the design department at Parsons School of Design. Your contribution to generations of New York City design graduates runs deep. How does your role as a professor and academic connect to your job as a designer? Is academia a place of experimentation for your work or a place of research? What changes have you seen over the years in design schools in terms of their focus, curriculum and the students themselves?

CB: From the very beginning, my work has been balanced between professional practice and educational activities. This fortunate arrangement has allowed me to collaborate with global industries while continuing cultural research and creative experimentation. My present position as Chair of Industrial Design at Pratt Institute is both challenging and rewarding. Pratt is one of the oldest and best-known design schools in the United States. The history of the Industrial Design department was shaped by a notable list of American design professionals, and its curriculum boasted a unique methodology of three-dimensional form generation.

Yet today, the field of American industrial design presents a vastly different picture. The very notion of design has expanded into business, social and even political spheres, transforming it into a field meant to provide courses of action, rather than objects and forms. To provide a sense of direction in this truly boundless field, I took to defining the mission of our department as “designing a better quality of life.” Alejandro Aravena, curator of the fifteenth Venice Biennale of Architecture, wrote that “the notion of quality of life ranges from very basic physical needs to the most intangible dimensions of the human condition.” I guide my students to pursue this elusive goal in very different situations, from exercises in 3-D form to assignments on socially responsible design. Critical observation and examination of daily behavior patterns are meant to provide students with fertile ground for reevaluating hidden potential in existing product typologies.

This, after all, has long been a goal in my own design practice.

TLmag: A lot of the products you design are connected to the idea of the souvenir, to memory and to history—not always happy moments, but more often tragedies and disasters, as in your iconic Buildings of Disaster series. But there is also your recent book, Keepsakes. Can you talk a bit about your interest in this subject as well as your reason for memorializing sites that met a disastrous end?

CB: Since the beginning of industrial design, the effort of the profession has been directed toward ideas of function and utility. Good design is usually synonymous with design that “works.” Non-functional objects—souvenirs, toys, collectibles—have been automatically excluded from the field. I claim that the time is ripe for redefining usefulness. In a world where culture has become a major determinant, design needs to find a new paradigm, to uncover a different mode of working—one based less on performance and more on communication, emotion and memory

In this context, the notion of souvenirs is both timely and essential. They are metaphysical containers into which the owners put their own meaning and emotions. “Memories lie slumbering within us for months and years, quietly proliferating, until they are woken by some trifle and in some strange way blind us to life,” wrote W.G. Sebald. Souvenirs are designed and made to serve as that trifle.

My studio has worked in this genre for almost two decades, and I have written and lectured about it extensively. Our most famous collection is, of course, Buildings of Disaster, the monuments to tragic or terrible events. In the words of Professor Jamer Hunt, the power of the project comes from “the compression of the extraordinary into the ordinary.” The objects help mitigate an incomprehensible void precisely by virtue of their unprepossessing, even humorous, souvenir presence. Like comfort toys or rosaries, the pieces offer tactile reassurance and affirmation of the everyday. Coveted by collectors and included in the holdings of many design museums, these objects redefine the notion of usefulness for our own uncertain times.

TLmag: Looking at some of your early work, there seem to be direct connections to recent design trends in the United States. Searstyle from 1992, for example, is in many ways a precursor to the Ikea hack, just as your Recycle series from 1988 is to the upcycling trend that emerged in the early 2000s. You have also written about how these two collections helped lay the groundwork for your future designs as well, including your interest in everyday objects and cultural sampling and the role of the latter in design, for you and in general.

CB: In my previous writings I referred to the character of Curious George. This cute little monkey came from the jungle to live in the modern world, just as I myself traveled to America from the Soviet Union almost forty years ago. At first, George is excited by his new home, but soon he grows restless and starts to play and experiment with everything that surrounds him. For years, my studio has worked by reflecting on everyday aspects of American lifestyle and landscape, on familiar things that often pass unnoticed because of their very proximity. Someone described my approach as a prolonged culture shock. This status of a perpetual observer allowed me to turn things like the Sears Catalogue into a furniture movement called Searstyle, or nondescript snapshots of Upstate New York roads into a collection of Upstate porcelain plates. The mechanisms of such work are curiosity, the power of observation and a sense of humor. This process of discovery is universal—I see it in younger generations of designers. I feel proud thinking that I might have inspired some of them.

TLmag: How do you see New York’s role as a creative capital today and going into the future?

CB: We live in the era of great connectedness. The world of young people, in particular, is a unified one, where music, fashion, games and social media have become a global infrastructure that stretches far beyond national borders. I do not know if New York as a physical place will continue to be a creative capital. But I think that the idea of New York will live on well into the future. The idea of a huge, messy, multinational space, where anything is possible.