Dakin Hart – Noguchi’s Relevance

Dakin Hart, senior curator brought that same sculptural focus to the Noguchi Museum in 2013 and has since developed a dynamic yet succinct programme that imbues the historical icon with a contemporary voice.

What does it take to advocate, preserve, and interpret the life, work and philosophy of the multi-faceted master Isamu Noguchi? Dakin Hart, who is now at the helm of the New York museum founded by Noguchi himself, has the unparalleled task of upholding a prolific legacy that encapsulates different—and at times disparate—aspects of the Japanese-American artist’s convoluted story. Hart has worked in various large- to small-scale institutions throughout the United States including the Fine Arts Museums in his native San Francisco and the Montalvo Arts Center in nearby Silicon Valley. He also played an integral role in opening the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas. The senior curator brought that same sculptural focus to the Noguchi Museum in 2013 and has since developed a dynamic yet succinct programme that imbues the historical icon with a contemporary voice. Set in the appropriately diverse neighbourhood of Astoria, Queens and intentionally located across the East River from Manhattan, the model institution strikes a careful balance between an archival museum and artist studio in constant flux. Hart spoke to TLmag about his rare mandate and Noguchi as a leading force.

TLmag: What is your responsibility as Noguchi’s executor of sorts?

Dakin Hart: I have the privilege of working with Isamu Noguchi in absentia. Though he’s not here to speak for himself, his universal language still guides my work. The museum is monographic and contains Nougchi’s archive and catalogue raisonné. We deal with an enormous amount of material including finished products, works in progress, raw materials and at least five hundred thousand images. We’re in a paradigm shift in which we’re starting to look at the figure through his many roles and putting him back together as one creative brain. He was such a kaleidoscope that there’s little in the 20th-century that he didn’t touch on. The set designer for Martha Graham is relatively the same as the designer of Akari lamps or the carver of Blade Stone Basalt works. The creative class has always admired him for this flexibility. He was representative of contemporary practice where there are no real limits. It’s for this reason, among others, that Noguchi’s following is a self-selective ‘cult’ and that the museum doesn’t have to pander to a wider audience like other institutions in the United States.

TLmag: You mentioned transcending different disciplines—was Noguchi a Proto-Postmodernist?

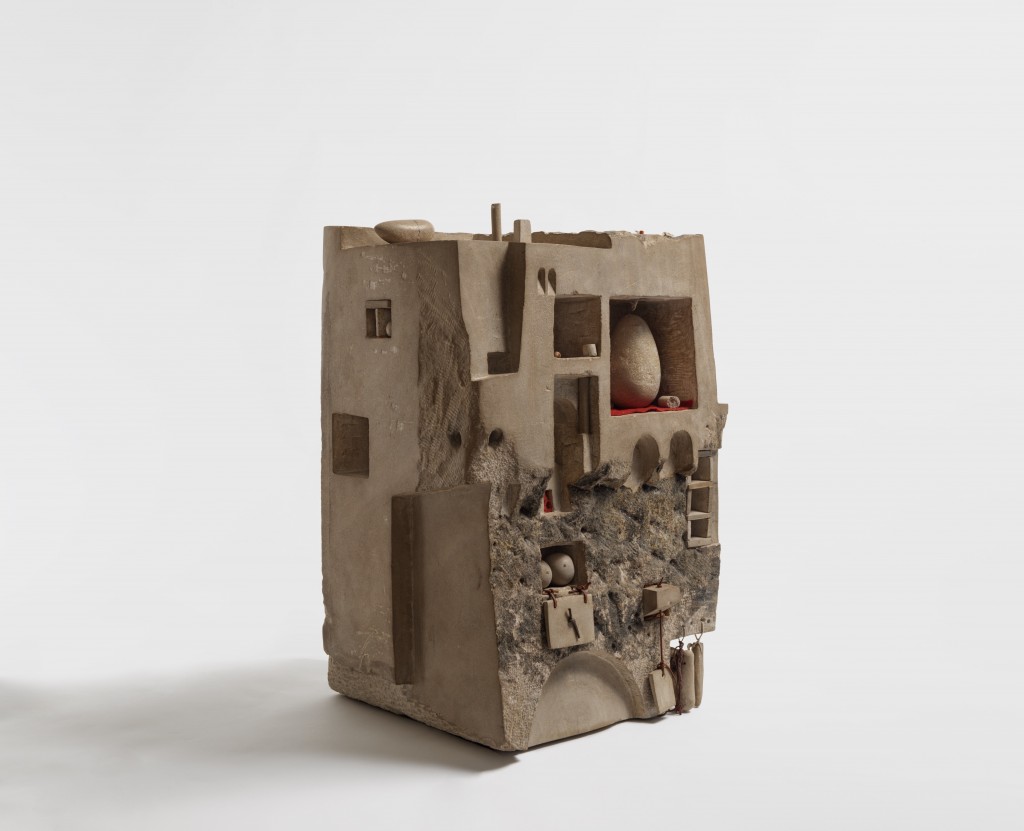

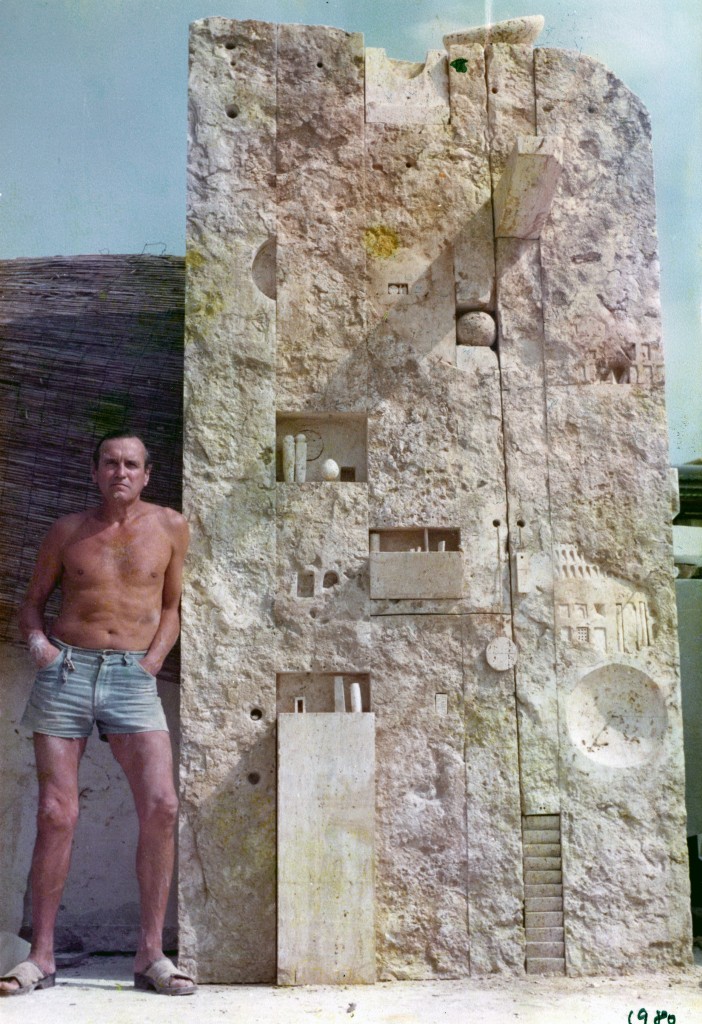

D.H.: Currently, we’re showing the work of Uruguayan sculptor Gonzalo Fonseca. Though Noguchi and he were close and shared certain principles, the former was never a Postmodernist. Still, he struggled with disciplinary categorisation – sometimes attributed to Modernism – and despised the balkanisation of creativity. As much as he remained contemporary throughout the 7 decades he worked (1920s to 1980s), Noguchi never lost faith in his ability to transform the world. Thanks to his long-time friend Buckminster Fuller, he considered himself a citizen of “spaceship earth”. After the dropping of the atomic bomb on his father’s homeland of Japan, Noguchi doubled down with in the belief that sculpture should be a meaningful social practice. First and foremost, Noguchi was fascinated by civilisation. I always say that sculpture is about civilisation whereas painting is about culture. The working history of the latter is 500 years old, whereas the former goes back 10 thousand years. Part of his interest in sculpture came from wanting to reconnect Modernism with that lineage. He often looked to times when sculptors acted as architects, engineers and inventors.

TLmag: In what ways did he pull from Eastern and Western influences?

D.H.: In the late 1920s, Noguchi was given a Guggenheim grant and travelled to Paris to study with Constantin Brâncuși. There, he immersed himself in the Romanian artist’s orbit and continued to cultivate his sculptural practice. A few years later, on his way to reconnect with his father’s family in Japan, he stopped in Beijing where he interacted with Qi Baishi, an influential painter know as the Chinese Picasso of the time. The artist taught him the traditional technique of ink painting from which Noguchi used to create a large body of work. Despite the easy stereotype that Noguchi drew influence from Japan and America, he in fact was informed by a wide range of cultures. Throughout his life, Noguchi was trying to synthesise and blend different traditions in a modern context. He championed different craft techniques because of their ancient and deeply-rooted virtues. One example of that is the Akari Lamp he revived: he modernised the age-old Japanese industry by adding electric bulbs and simplifying the design. A lamp is primarily a tool for casting light, but he wanted to turn it into an object that shaped light as a primary material.

TLmag: What were some of his collaborations during his lifetime and through dialogue with his legacy?

D.H.: Robert Stadler, who we exhibited earlier this year (featured in TLmag 27) is an artist who was trained as an industrial designer. Such side-by-side presentations with contemporary artists help peel back layers of Noguchi’s work. In this sense, Stadler’s showcase shed light on Noguchi’s deeply conceptual approach that is often clouded by his Modernist affiliations. Both Noguchi and Stadler’s works are experimental, interdisciplinary and the result of risk taking. What is often underestimated in both their practices is the importance of play and their willingness to fail from time to time. Then there was his relationship with seminal dance choreographer Martha Graham which was powerful because neither one of them had any expectations of the other. Noguchi was creating abstract things that Graham then found unexpected uses for. The sets he produced didn’t require her to frame her pieces with narrative. Together, they were able to redefine the relationship between characters and objects. He invested that fluidity back into all other aspects of his work. In the 2000s, leading theatre artist and director Robert Wilson applied a similar approach and performative tradition when curating and designing an important Noguchi retrospective that travelled to over 11 locations across the globe.