Turning Australian Design Upside Down One Story at a Time

Is it possible to tell stories through design? Australian collective, Broached Commissions, believes not only that it’s possible but that it is essential.

In a dramatic black gallery in the heart of Melbourne stands a lamp. But not just any lamp. This lamp oozes discomfort, it’s three legs splay out below its oddly contorted body. Its head is angled downwards and towards its neck as if it is trying to avoid eye contact with visitors. Its skin resembles that of a hedgehog, or perhaps in this context an echidna, with spikes pointing outward, defending itself from the dangers of the world. This lamp is undeniably awkward but at the same time, it is intriguing. What is it afraid of? Why does it look like that? What kind of strange creature is this?

This is one of three Prickly Lamps created by Lucy McRae, who describes herself as a sci-fi artist and body architect. The Prickly Lamps are made from 279,000 toothpicks and they embody the need to fend off predators during the Colonial period in Australian history. The objects deal with an uncomfortable topic which points to the destructive impact that colonialism had on both the native aboriginal population and the flora and fauna of Australia. The lamps were created in 2011 for Broached Commissions’ Colonial collection and are now on show at the National Gallery of Victoria as part of a retrospective exhibition entitled, Design Storytellers: The Work of Broached Commissions.

But what is Broached Commissions? According to its Founder, Lou Weis, Broached Commissions is “essentially a creative direction production house”. Sitting somewhere between a design studio, a research group, a narrative driven design collective and an agency, it has an unusual structure.

The production house was established in 2011 by Lou Weis and founding designers Charles Wilson, Trent Jansen and Adam Goodrum with the purpose of commissioning designers to produce thoughtful, critical and narrative-driven pieces for the collectible design market. In doing this, Broached Commissions radically disrupted the Australian design scene. Weis describes his frustration this design in Australia is solely focused on the commercial sphere with a philosophy of importing European and America design styles. He set to create an Australian design language and culture whilst exploring what it might mean to be a designer in the 21st Century.

Likewise, Ewan McEoin, the Senior Curator in the Department of Contemporary Design and Architecture at the National Gallery of Victoria, felt there was a lack of design discourse in Australia. “Before the NGV started exhibiting design in 2015 there was nowhere in Australia to exhibit design,” he tells TLmag. Despite this late and overdue entry into exhibiting design, McEoin feels optimistic about its future which he sees “changing quite quickly” into a narrative driven practice. “This is not just an Australian paradigm; we see it happening globally. There is a sense that we need to be thinking about how we understand the world around us through design more.” He credits Broached Commissions for pioneering this attitude in Australia and encouraging a growing community of creatives to reconsider the possibilities that lie in their practice.

The exhibition is a celebration of the challenging, poignant and often political work that Broached Commissions has created to date. Bringing together their four collections – Broached Colonial (2011), Broached East (2012), Broached Monsters (2017) and Broached Exceptions (2018) – the exhibition makes visible the connections between the pieces and allows the public to become familiar with a new way of thinking about what design can be. McEoin says “For the audience, just the idea that you can tell stories through objects is a revelation.”

To develop these stories Broached Commissions has established a rigorous working methodology which relies on in-depth research into a certain field. This research is then moulded into an essay that becomes the focal point for the collection. Following this, designers are invited to discuss, debate and delve into the context and then create their own research paths and work related to the topic. Lou Weis reflects that his filmmaking background influenced this way of working: “It is like film, we take a story that is really popular and well-known and then attack it from a very different angle in terms of mood, gender relations and other things to modernize it.”

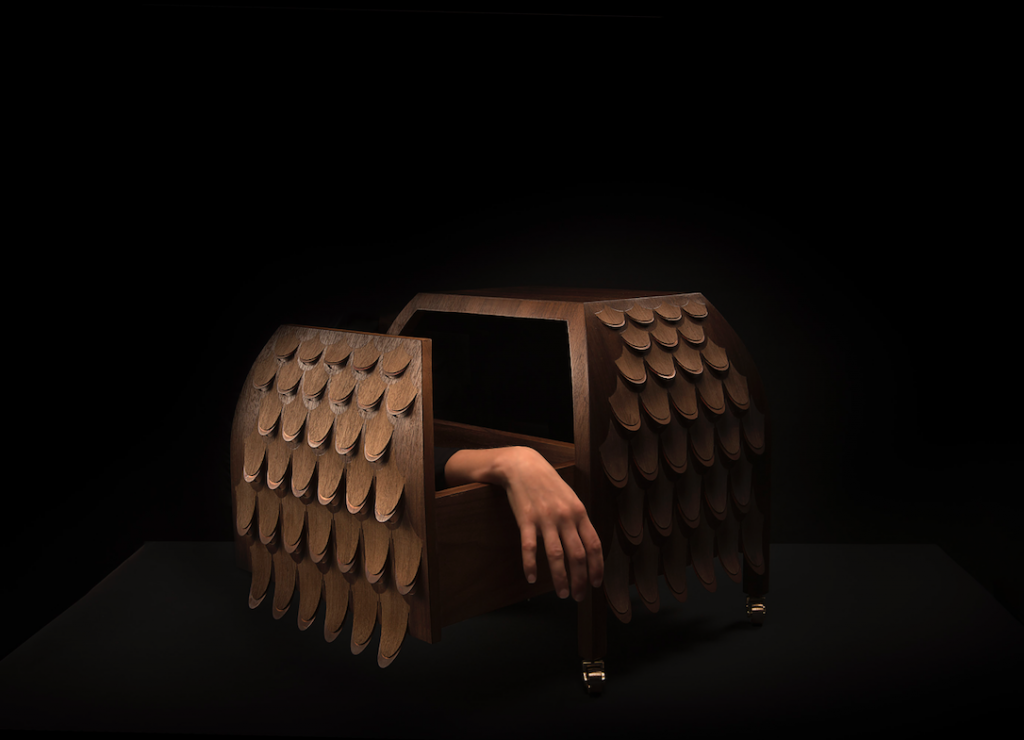

The Broached Monster collection by Australian Designer, Trent Jansen, is a good illustration of how this process pans out. It was the result of five years of investigating the mythology, folk-tales and suspicions of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in the early period of colonial Australia and the fear and cultural clashes that these created. The visceral objects fall into two series: The Hairy Wild Man From Botany Bay is made up of a chaise lounge, chandelier and bowl which seem almost alive in their furriness and reference the British folk-tale about a nine-foot-tall being that lurked in the bush; And Pankalangu which alludes to a mythical creature from Aboriginal stories which comes to life in Jansen’s finely constructed scalloped wardrobe, armchair and side table. Jansen’s pieces present a new vernacular in which Indigenous and European myths and aesthetics are mixed together. The work suggests that by reimagining urban legends as well as the objects we surround ourselves with there is the potential to create a new national language that is inclusive of both cultures.

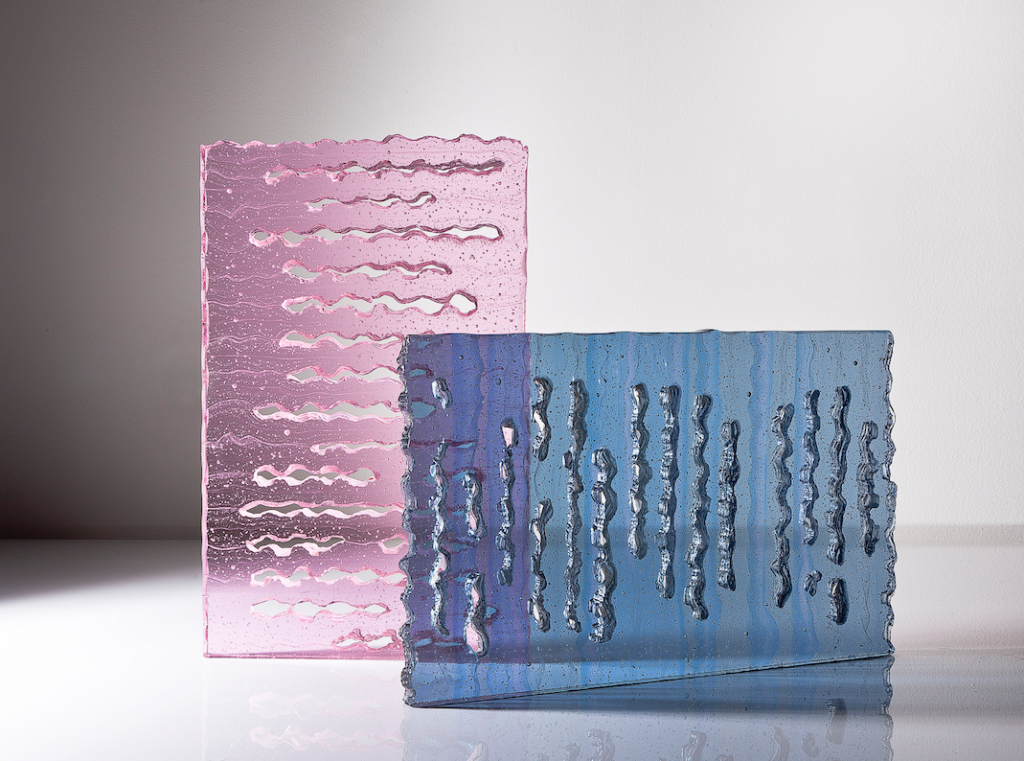

The newest addition the Broached Commissions portfolio is the work of Korean/American artist Mimi Jung who approaches the forces and consequences of globalization from a very personal level. Having been pulled to America as a child when her family relocated, the artist explores the dislocation that the contemporary phenomenon of increasing migration has both at the micro and macro scales. In gentle tones of blue and pale pink, Jung’s Glass Work series conveys the complexity of a life interrupted with their voids and rugged edges contrasting the smooth front and back surfaces.

This theme of migration and globalization is something that was also explored in Broached East which looked at Australia’s relationship to Asia in the mid-late 19th century. This project marked a shift in how Broached looked at itself. “We realized that what we were doing was trying to find the face of globalization. The question then became, what happens to material culture as it becomes commodified and pushed around the world?” asks Weis.

Once piece that rises to the call of this question is The Paludaruim Shigelu, by Azuma Makoto. It considers the practice of uprooting and exporting through a modern Wardian Case. Makoto created a system in which a plant can be encased so that is can survive anywhere at any time of the year, rendering something natural as a product that becomes an exoticized specimen in foreign lands.

Other works from both international and local designers that make up the twenty-four-piece retrospective include British designer Max Lamb’s, Hawkesbury Sandstone furniture collection, Australian born Charles Wilson’s, Tall Boy furniture, Ma Yansong’s MAD Martian Candelabras, Adam Goodrum’s, Birdsmouth table and Chen Lu’s, Dream Lantern. Many of the works use Australian materials such as red gum wood and wallaby pelt, also contributing to a new Australian design language.

In terms of Broach Commissions next steps, Weis reveals that it is “amping up to do more internationally in the next few years.” In the meantime, the exhibition makes a compelling case for the creation of narratives through design. Whether through a “slightly hideous prickly lamp” (in Weis’ words) or anthropomorphic furniture, the need to tell old stories and create new ones seems like an urgent task that will affect our value systems and resonate into the globalized future.

‘Design Storytellers: The Work of Broached Commissions’ will be on display at the National Gallery of Victoria until February 2019.