From Island to Archipelago: Luca Nichetto

We talk to designer Luca Nichetto about his childhood in Murano, living and designing in Scandinavia and his new lighting collection ‘Fusa’ for Svenskt Tenn

In 1219, the Venetian government banned all glassmaking furnaces from the city of Venice and moved them to an island to the north of the city called Murano. This move was strategic in two ways. Firstly, it ensured the safety of the crowded city of Venice by removing the risk of fires. But secondly, it also ensured that the master glass blowers were isolated, protecting their precious and valuable glassmaking secrets on an island of creation. The glassblowing skills were so highly valued that anyone who divulged them risked the penalty of death.

800 years later, the rules and regulations around the island and its glassblowing community have, thankfully, relaxed. However, being born and raised on the island of Murano still makes you privy to a unique and traditional way of life that centers around the material of glass. Designer Luca Nichetto comes from a long line of glassmakers who have passed their knowledge from generation to generation. Departing from the traditional route of remaining in Murano to pursue a career in glass, Nichetto splits his time between his studio in the archipelagos of Sweden and Venice. His latest collection of lighting, Fusa, for the Swedish interiors company Svenskt Tenn mixes his Italian past with his Scandinavian present.

TLmag caught up with Luca Nichetto to discuss how the island of Murano has shaped his practice and the experience of living in Scandinavia:

TLmag: Let’s start at the beginning, what it was like to grow up in Murano?

Luca Nichetto: On the island, especially in the mid-70s when I was born, 99% of the population was living off the glass industry. My grandfather was a glass master, specializing in making chandeliers, my mother decorated glass and a lot of relatives and friends were also involved in the industry. So it was quite normal for me, as a kid growing up in this kind of environment, to see the tools and drawings used for this kind of work and then I would see how these drawings became objects. To see that was something very natural.

Later on, I went to study in Venice at the Institute of Art. For obvious reasons, I chose to specialize in glass. During the summertimes my classmate and I went knocking on the doors of different factories with a folder full of drawings, selling these designs—not because I wanted to be a designer because I didn’t really know that job existed but just because we wanted to make some money to have fun during the summer time.

Then, I went to the University of Architecture in Venice as it was opening a new course in Industrial design and it matched very well with what I wanted to do.

During my studies, a lot of professors called me “Glass Boy” because everything that I was doing or designing was for glass. For me, this was because I could really see an object materializing from my ideas and drawings in glass.

The ritual of knocking on the doors and doing this tour also continued [laughs]. During that time, before I finished my studies I was lucky to knock on the door of Salviati, a very important manufacturer a the time.

The art director of Salviati was Simon Moore, a British designer who specialized in glass. Simon looked at my folder full of drawings and he said I want to buy everything and I was thinking “Wow, it’s going to be a fantastic summer for me! What luck!” but he also mentioned that he probably would not realize any of the pieces. I asked him why he was buying them and he said: “I want to show you that I really appreciate and see that you are talented but you need to get some experience.” He asked me to pass by Salviati once a week and he could teach these things to me. Doing that, I met designers such as Tom Dixon, Ross Lovegrove, Thomas Heatherwick, Ingo Maurer and many others and other design students. I was very inspired by these people so it was an amazing time.

Finally, in 1999 I received a brief. I was 23 and I had the opportunity to try to develop a design for Salviati. Luckily the vases that I designed called Millebolle became one of the best sellers and are still in production. In the meantime, I applied for an internship at Scalini, the lighting company. My attitude at this time was to constantly think about glass but also be very curious in exploring other materials as well. This was how my career started.

And then, later, you moved to Stockholm…

I live in Sweden now but I have two studios, one in Stockholm and one in Venice.

How do you find working between these two diverse places in terms of different attitudes to design?

There are a lot of differences. I think in Italy, for many reasons, establishing a career as a designer is much more difficult than in the rest of the world. There is such a competition with all the old masters and other colleagues. You really need to struggle to find your own path—much more than in Scandinavia.

In the approach to design, I think the main difference is that Scandinavia is not producing anything anymore in terms of craftsmanship. Everything is now being produced in Eastern Europe or in China. Design in Scandinavia is functional and timeless which I think is one of the positives of Scandinavian design. In Italy, design is still much more related to the craftsmanship and the emphasis that the object can create, more than the functional aspect.

Where do you position yourself between these two design worlds?

For me, to find the balance between the two approaches is very interesting. We need to consider that historically the Scandinavian and Italian design are probably two of the most important places that have shaped how we think about design now.

At the moment, I am quite critical of Scandinavian design because I think there is a lack of quality. On the other hand, for me, quality is not only about cost. You need to make products that allow people to understand that there are skills behind them that take time to achieve. Tradition and legacy are things that we still need to care about, otherwise, in the future, we will live in standardization world which will be much more similar to the Soviet Union than we think it will be.

The Fusa lighting collection that you designed this year for Svenskt Tenn is quite interesting in relation to that idea because they are inspired by the history and legacy of the company. Is this approach of reflecting on the past to inform your designs a recurring method in your practice?

I think knowing the history is important but we also need to look to the future. In that sense, understanding the heritage of something is important, however, it depends on the company that you are working with. If it is a start-up of just three years then it is quite difficult to understand the heritage. If you are working for a traditional brand with a long history it is much easier to understand where their DNA has come. For me, the most important thing is to observe and understand the partner-in-crime that I am working with.

In the case of Svenskt Tenn, everything started from an exhibition that their founder, Estrid Ericson did in 1938 when she went to Murano. During the Second World War, she brought a collection of glass back to Stockholm and held the first exhibition of Murano glass in Scandinavia. After 70 years, because Svenskt Tenn works a lot with their archives and their history, they became interested in this exhibition of Murano glass. I was the perfect person for them because I am a designer from Murano but I live in Sweden. They approached me to ask if I was interested to do something with them.

How did you approach the brief from Svenskt Tenn?

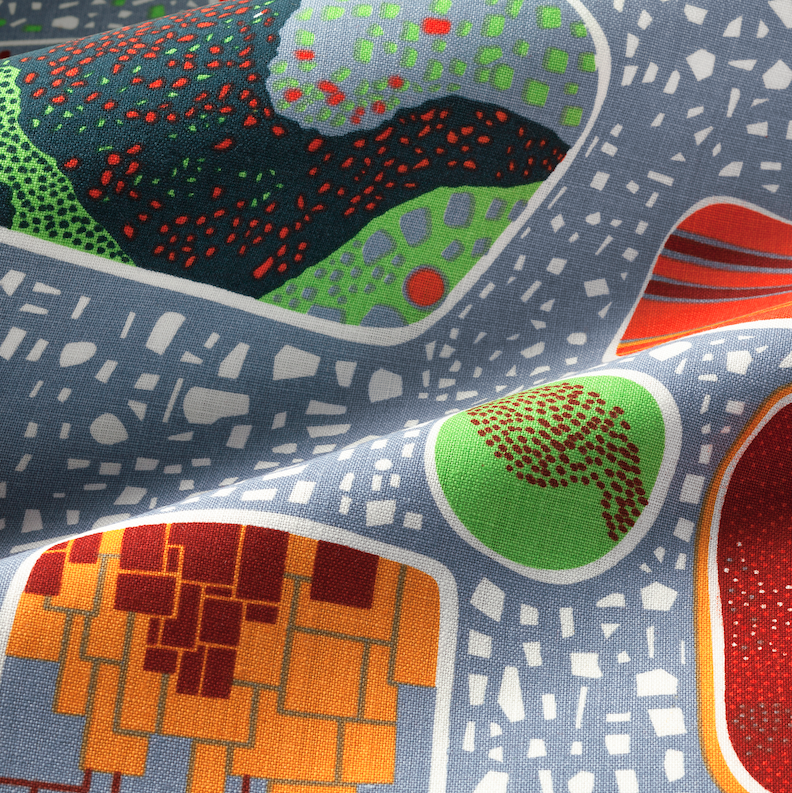

My idea was to look at their iconic textiles. In particular, the textiles of Joseph Frank. 98% of his textiles are very floral and decorative, however, there were two items that he developed called ‘Terrazzo’ and ‘Mosaic’ which are much more abstract. When I saw the design of Terrazzo, I immediately felt that this pattern could be made in glass. Glass and terrazzo are also very connected to the history of Venice as terrazzo was used for the first time in the Palace of Venice.

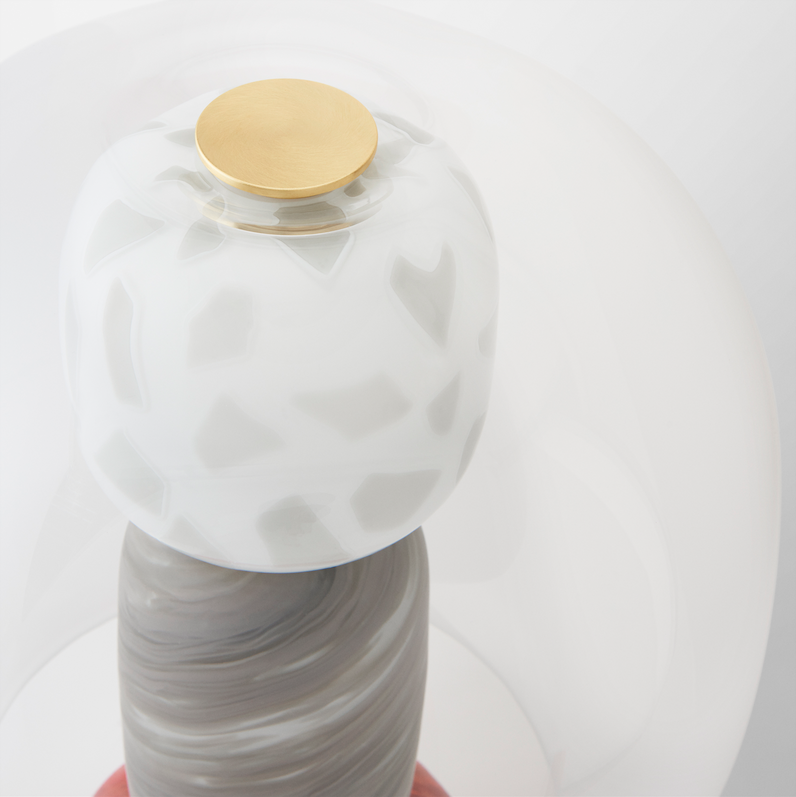

I literally took a piece of the textile and cut out a pebble and started to play with it to figure out how I could make the effect with glass. Later on, thinking of terrazzo, which is small pieces of marble or stone, I thought I should use the old pieces of glass that usually get thrown away. So there was an upcycling process with the colors being made from small fragments of glass.

I decided to call the collection ‘Fusa’ which, in Italian, means melt. It is not only because the lamp is melted or is glass but also because the product is a kind of melting pot—part of it is the heritage of Svenskt Tenn and part is my heritage in Murano that come together to create that object.

Could you talk a little more about the upcycling of the waste material, is this a common practice in Murano with glass?

It is not a very common practice. We had to find a technique to create a kind of melted terrazzo. You need to know the production methods. In the design, it was important to consider that the pieces will be made in Murano but need to travel to Scandinavia. It was difficult to create a colorful collection from what we call “pot color” which is a kind of slang for the color that is melted in a pot—if we chose exactly the colors we wanted it would be much more expensive and difficult to control for a company that is not based in Murano. So the idea was to reuse the colored pieces that they would normally throw away to find the perfect compromise between beautiful aesthetics and, at the same time, find a new process that can be applied to these kinds migrating objects.

The ‘Fusa’ collection will be on display at Svenskt Tenn’s ‘Heritage’ exhibition, in the Stockholm store on Strandvägen 5, until March 31