Jongjin Park: Porcelain Paper

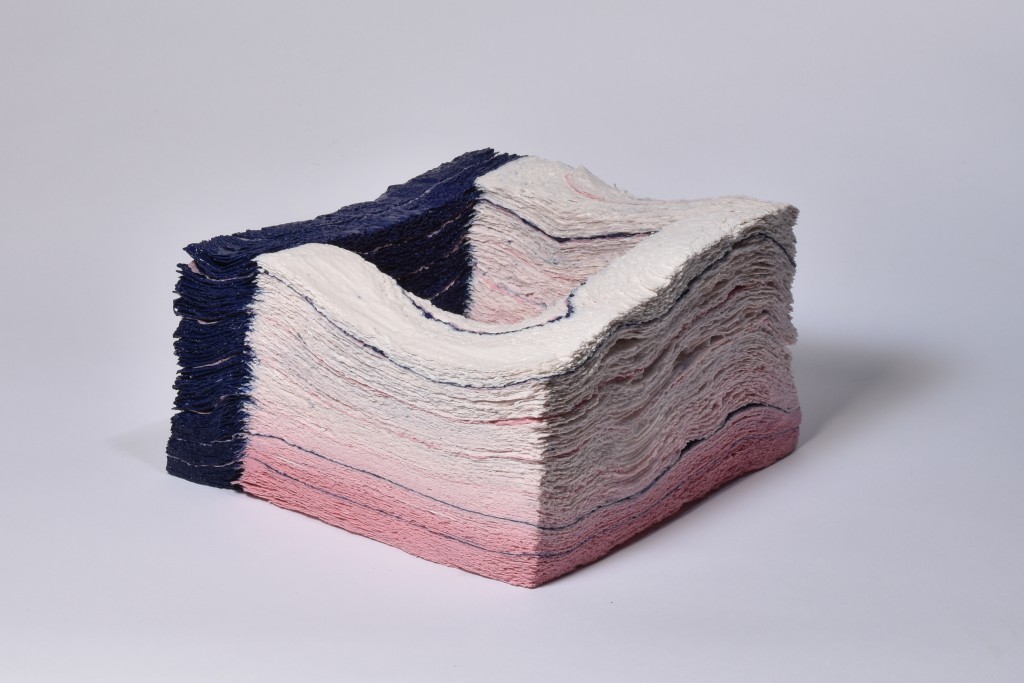

Channelling the conceptual framework of an age-old Korean technique, experimental artisan Jongjin Park seeks to emulate the value of co-existence in the bespoke combination of paper and porcelain. The result is a series of iterative ceramic vessels.

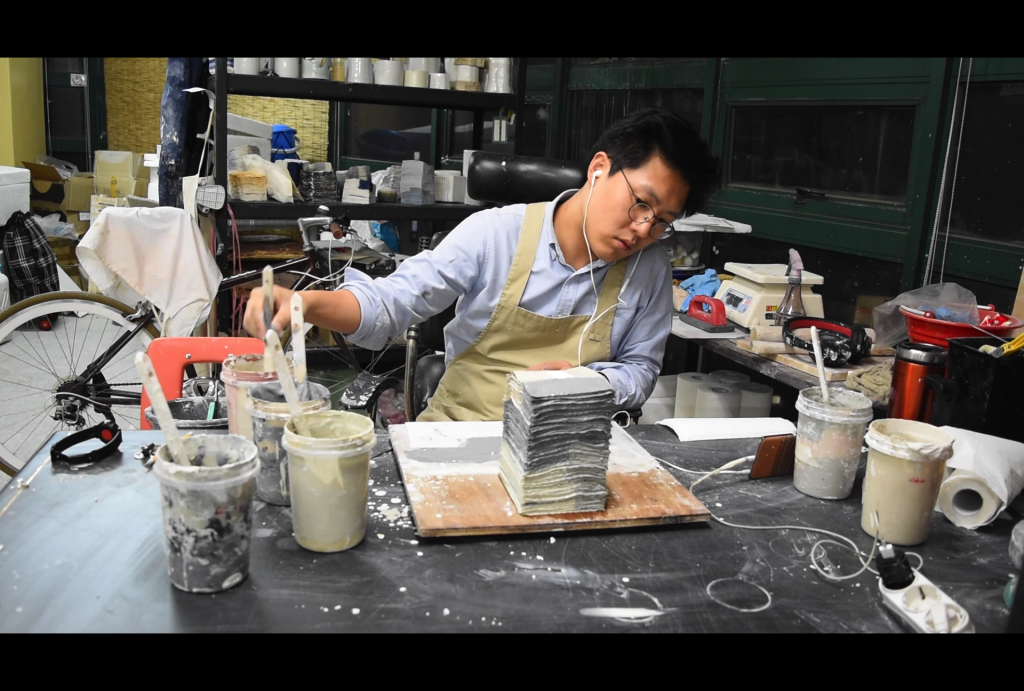

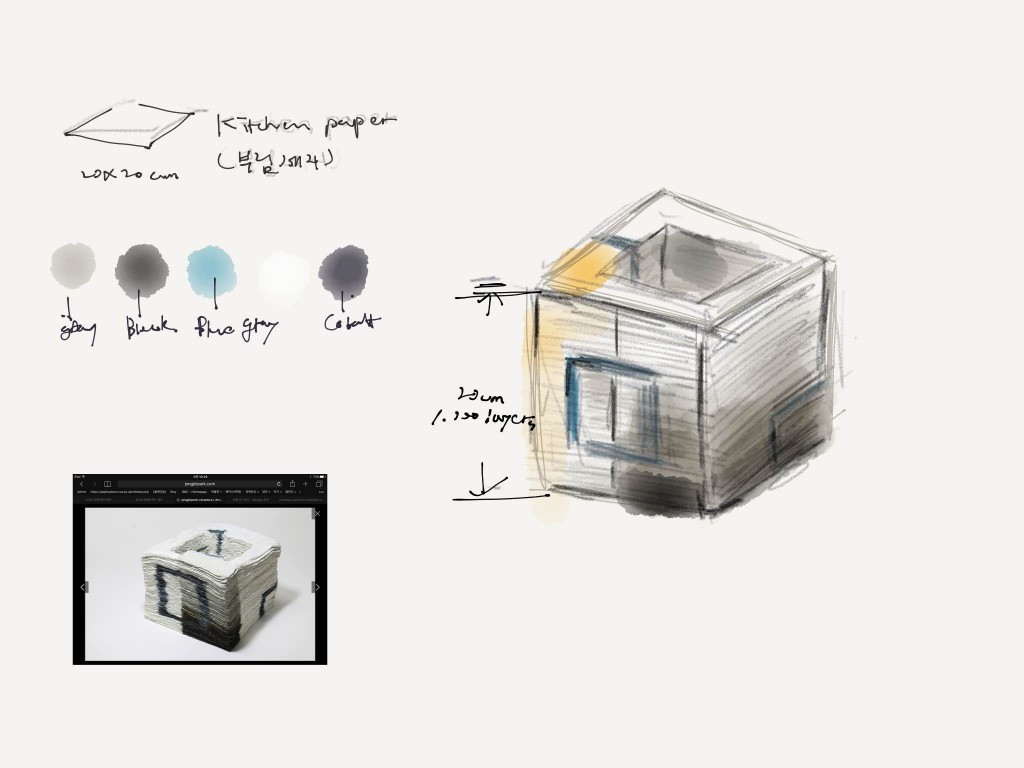

Experimental ceramicist Jongjin Park often challenges the limits of material; the characteristics we usually ascribe to composites like paper. The South Korean talent has spent the better part of four years developing the Artistic Stratum series. At its core is a bespoke technique that combines everyday kitchen paper-towels with porcelain slip. Combining these seemingly polar materials, Park creates layered millefeuille vessels. His results play against the conventions of perception; sturdiness is masked in a trompe-l’oeil suggestion of fragility. This could only be achieved with a keen set of honed skills allowing for refinement. Having completed his masters at Cardiff Metropolitan University, he is currently pursing a PHD at Kookmin University Seoul. Park has exhibited at events and venues the world over, including Brussels-based ceramic authority Puls Gallery (Featured in TLmag 24). We spoke to the maverick about his motivation, process and perspective.

TLmag: The use of paper seems to imbue your work with a visceral and visual quality. From where did your fascination for this material first derive?

Jongjin Park: During my second Ceramics MA in Cardiff, my professors suggested that I shed the trajectory in which I had been trained. My previous research was focused on the Korean porcelain Moonjar traditions. However, this upper and lower joining technique provided me with philosophic and formal inspiration. Applying this understanding to a new British context and atmosphere revealed my appreciation for ubiquitous materials.

TLmag: Describe the process you employed to incorporate the properties of paper into porcelain vessels. How has ongoing experimentation evolved over time?

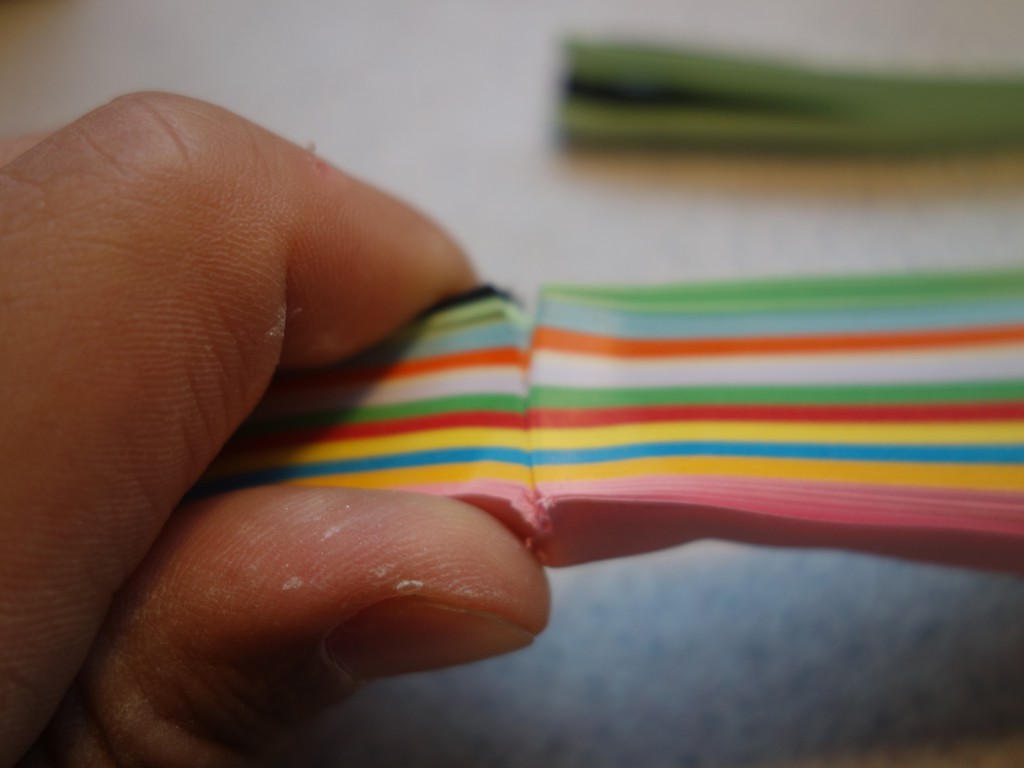

J.P.: The paper-like material is layered by painting porcelain slip on each sheet. After achieving 3d-form, I used power tools to shape the final outcome. As it’s hard to shape porcelain after being fired at 1280℃, it’s important to determine each piece’s form beforehand. However paper will change properties in this condition. The ability to combine two different co-existing actors came from my experience with the Moonjar technique – a process developed during the Choseon Dynasty (1392-1910). In this tradition, glaze is used to connect different components. Exploring this process as a conceptual framework allowed me to determined various visual and invisible solutions; ultimately achieving a harmony. It also suggests what coexistence means for humanity.

TLmag: Are ceramics more forgiving than other materials, when experimenting with new combinations, forms and techniques?

J.P.: On one hand, clay is eco-friendly, inexpensive and tactile. On the other hand, the material can only achieve certain forms and proportions, due to firing constraints. One has to master the nuances of ceramics; how different variations react. These limitations are motivating. Challenging set rules lets me work freely.

TLmag: Why is it important that your work reveal process? How is this evident in final pieces?

J.P.: The process of my work is about layering time as formative expression. Working becomes a form of meditation; It’s just me and my thoughts. Sometimes, dramatic emotional shifts are manifested in strong colour choices or intentionally fabricated gaps between layers.

TLmag: In your mind, what defines craft?

J.P.: Craft is a condition of slow innovation, which itself changes the world. Positives and negatives exist simultaneously. After humans discovered various ways to deal with materials – touching, adapting, and transforming –, they were able to shape containers, jewellery and common objects. From then on, use was the most important factor in defining craft. However, Today, aesthetic impression has taken over. This change occurred in the last century of a thousand-year history.