Pao & Naoto: Exploring the Essence of Paper and Urushi

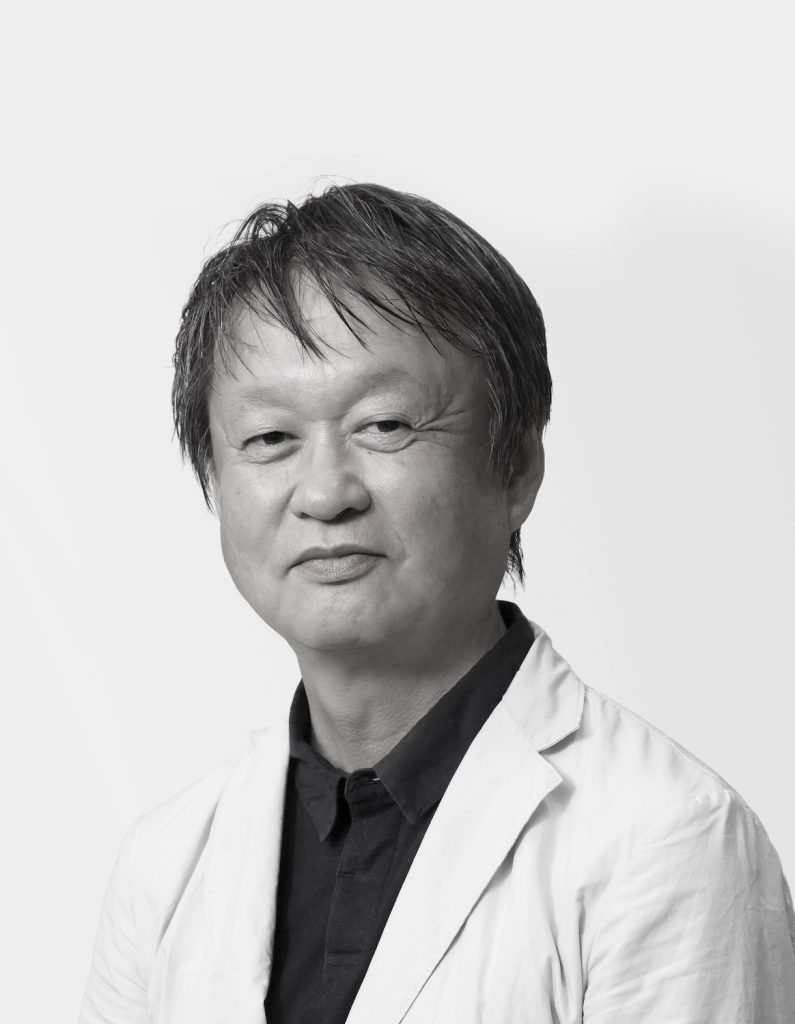

Dive into a fascinating conversation between Japanese mentor Naoto Fukasawa and Taiwanese emerging artist designer Pao Hui Kao, where they unearth the profound connection between paper, Urushi, and nature. This exchange appears in the 2023 issue of TLmag39: The Culture of the Object.

Guided by Lise Coirier, this exchange between Taiwanese artist and designer Pao Hui Kao and Japanese designer and mentor Naoto Fukasawa, paints a vivid picture of the age-old crafts taking on contemporary artistic and design interpretations. Through their words, Naoto and Pao advocate for realigning with the lunar calendar—a tradition that the West has lost touch with, yet, promises a stronger bond with our roots and nature.

Lise Coirier (Lise): As a 2022 Loewe Craft Prize jury member, what were your initial thoughts on Pao’s Black Urushi Paper Pleats Bench?

Naoto Fukasawa (Naoto): The first thing that struck me was its lightness. At a glance, I didn’t even realize it was a bench. It felt fragile yet had a surprising sturdiness. Pao, in my view, is brilliantly exploring paper’s potential—not just as a craft but also as an art form.

Pao Hui Kao (Pao): Hearing you describe my work is an absolute honor. Thank you.

Naoto: Your creations shouldn’t be confined to labels like art, design, or craft. They exude beauty and showcase extensive material research, with each piece narrating its own expressive story.

Lise: Naoto, can you share your connection with paper in some of your recent projects?

Naoto: I’ve been collaborating with traditional paper companies in Japan, crafting innovative designs, like a paper door, shoji. It’s a fusion of thin wood and paper that offers translucency, allowing light to filter through. I’ve also developed a range of bags using the non-wrinkle tensional paper, under the brand S-I-W-A (Siwa means wrinkle). It’s a testament to repurposing existing technology to serve contemporary needs.

Lise: Can you discuss some of the projects you’ve been involved in, especially your collaboration with companies like Muji, which has a notable emphasis on paper products?

Naoto: Paper is inherently flat, and historically, it’s a natural material. Muji is revisiting that original, eco-friendly essence. Kraft paper, which is both commonplace and synonymous with Muji’s brand identity, connects people to nature because of its organic feel, setting it apart from man-made materials. Its distinct color has also become emblematic of Muji’s brand.

Lise: Does Muji use washi paper?

Naoto: Not exactly. While washi is handcrafted, Muji, being a large-scale producer, finds it challenging to source handcrafted washi in the quantities they require. We hold a deep appreciation for artisanal methods and always strive to imbue our industrial products with that natural touch.

Lise: So, would you say that paper is a core element in your design philosophy?

Naoto: Undoubtedly. I gravitate towards paper, wood, and other natural materials – avoiding plastic. I favor designs that exude a rustic and organic charm.

Pao: Some view paper as fragile and transient – it can warp in humidity and age over time. Given these characteristics, why do you think paper remains an integral part of our daily existence?

Naoto: Beyond mere functionality, paper brings a sense of tranquility and closeness to nature. Though seemingly counterintuitive, even in high-tech domains, there’s room for paper. Consider airplanes that once had paper components or traditional Japanese umbrellas (Wagasa) crafted from bamboo and paper. In Kyoto, these umbrellas are still in use. Made from materials like washi, bamboo, wood, linseed oil, and lacquer, they undergo an “oiling” process for waterproofing (Abura-Hiki), and depending on the weather, their drying time varies. From daily essentials to fashion statements, Wagasa highlight the unique and enduring tradition of Japan.

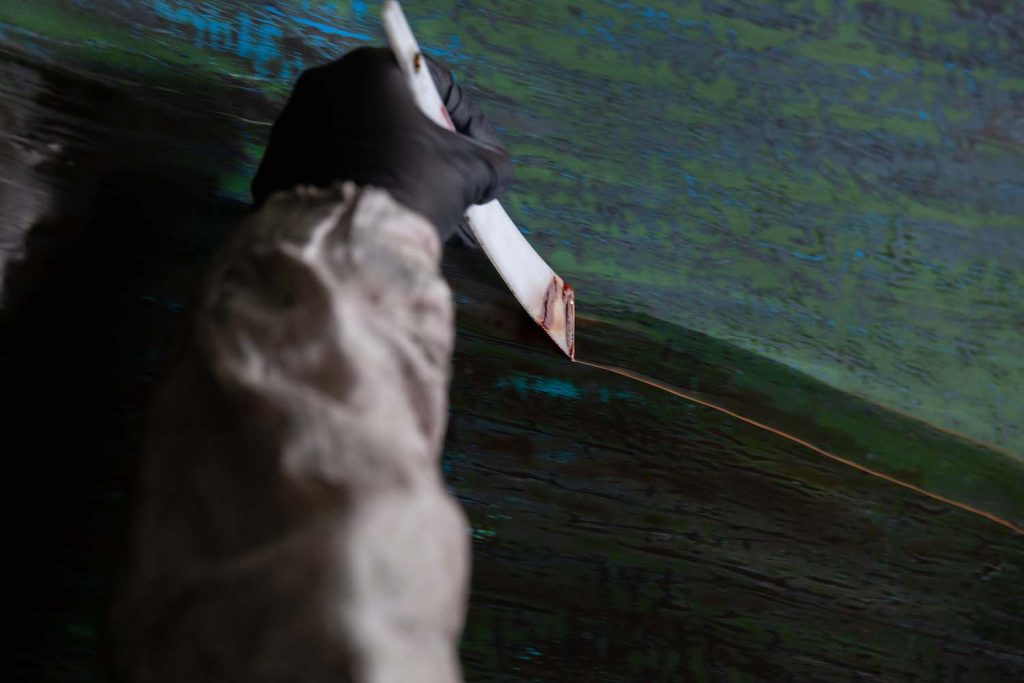

Pao: My respect for Urushi workmanship has deepened, especially after my residency in Aizu Wakamatsu, where I spent three months under the guidance of an Urushi craft master and came to realize the complexity of its application. After returning to the Netherlands, my journey with Urushi took a different turn. Instead of strictly adhering to traditional methods, I introduced an element of ‘playfulness’. When something didn’t turn out as expected, rather than sanding it away, I sought to communicate with the imperfections, sometimes even adjusting my original plan for that piece. I understand that some purists in the traditional Urushi community might find my approach irreverent. However, my aim is to explore new possibilities for this incredible material. I’m curious about your perspective, Naoto. How do you strike a balance between creative reinvention and preserving a traditional craft?

Naoto: I’ve always seen Urushi as more than just a decorative layer for objects. It’s extensively used in architectural and furniture contexts as well. However, when applied over wood, it doesn’t ensure permanence, given the nature of the wood. Urushi serves as a protective layer, akin to lacquer. What sets it apart is its natural origin, making it an intriguing invention from nature. As we move forward, there’s a need to prioritize such natural alternatives over synthetic coatings.

Lise: And let’s not forget the scarcity of Urushi. It’s only becoming more expensive as time progresses.

Naoto: True. Its scarcity is intrinsically tied to its traditional harvesting methods. But there’s potential. If we could innovate in terms of manufacturing or expand its cultivation, not only could we have more of it, but possibly even enhance its quality.

Lise: Given the need, should we consider planting more Urushi trees, perhaps even an entire forest in the Netherlands? Is this viable, or is the Urushi tree unique to Japan? Could we potentially introduce it to Europe?

Pao: It’s an interesting idea. First, we would need to review importation regulations. As I understand it, the Urushi tree thrives best in its native environment. However, I’m open to experimenting with growing the tree here in Holland.

Naoto: Your approach to using Urushi differs from traditional methods. I’m curious, why did you choose to work with Urushi?

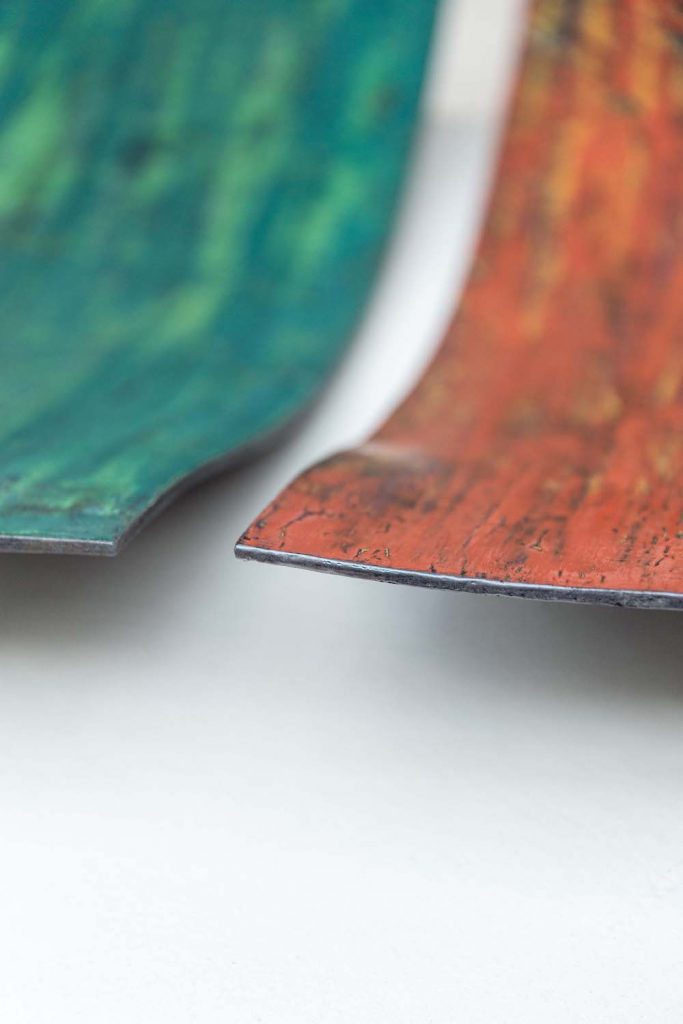

Pao: Many collectors often posed this question. Initially, I worked solely with paper. Some would ask, “If I spill water or coffee on the paper, is there a protective layer?” I’ve always been against using chemical coatings. My fascination with Urushi began when I was in Aizu Wakamatsu, apprenticing under an Urushi master. I learned everything from tree cultivation to its application. It became clear that Urushi should be the protective layer for my paper works. Despite its challenges, like potential allergies, the material intrigued me. The symbiotic relationship between paper and Urushi became evident as I delved deeper; both are derived from trees. My paper pieces emphasize the wrinkles and textures created by the fibers, showcasing the transformation of paper into a robust material. Applying Urushi not only added protection but also accentuated these wrinkles. The two materials complement each other beautifully. My Lacquer Leaf Trays I have created for my “25 Seasons” Solo Show at Spazio Nobile, are a testament to this union. The design on the tray reveals the original paper wrinkles, enhanced by multiple layers of Urushi. While traditional craftsmen might manipulate the surface to create patterns, the patterns in my work are innate to the paper.

While designers often micromanage every detail, I prefer letting the materials breathe and express themselves. It’s why I’m in love with Urushi and paper; they offer endless possibilities. With Urushi, factors like the weather play a significant role, influencing the wrinkles on the paper. It’s unpredictable, and many might find it daunting since you can’t control these elements. But I embrace this unpredictability. I don’t dominate the materials; I feel I mentor them, guiding their synergy. Traditionally, Urushi was used on wood or glass. Applying it on paper is unorthodox, perhaps influenced by past perceptions about paper’s longevity. What’s your take on merging Urushi and paper in contemporary times? Do you feel I am challenging Japanese traditions in this way?

Naoto: Your approach feels like a fresh take on Urushi technology. Traditional Urushi painting has specific techniques to coat surfaces evenly, like in Kishu Lacquerware where one craftsman prepares the wood base while another applies the Urushi. Your method of letting Urushi absorb into paper, making it intrinsic to the piece, is groundbreaking.

Pao: It’s fascinating. During my time in Aizu Wakamatsu, I observed the traditional wood base and Urushi application. But it’s only now, after this discussion, that I see how I’ve melded both roles. Is it maybe too ambitious?

Naoto: The Loewe Craft Prize champions the marriage of tradition with innovation, and you’ve captured its essence. It’s not about pigeonholing craftsmen into categories. It’s about leveraging traditional materials to enhance contemporary life. Your position as a finalist is testament to your singular vision and skill.

Lise: Given the varying weather conditions in Europe, is it challenging to use these materials?

Pao: Absolutely, working with Urushi in Europe presents unique challenges. The climate here, especially considering the ongoing shifts due to climate change, is vastly different from Asia, places like Japan or Taiwan. The conditions can sometimes be less than ideal, causing unexpected results. Yet, I continually experiment and adapt because I genuinely love the process. While the weather might occasionally be unfavorable, leading to results I didn’t initially envision, I use these surprises as opportunities to innovate and push boundaries.

Naoto: When working with Urushi, how do you envision its multifaceted nature – the colors, layers, and thickness? It seems like there is a depth of beauty in this one material.

Pao: You’re right. My approach involves applying Urushi solely to paper. Paper feels alive, always evolving. I could use chemicals to stabilize it, but I prefer to preserve its organic quality. Each time I layer Urushi onto paper, it undergoes a transformation. This process is a dialogue between the paper and Urushi. Probably, the interaction between these two materials would likely be less dramatic in Taiwan or Japan. The European climate environment intensifies the challenge, which I find enthralling. Here, I’m exploring the possibilities of a traditional Asian material in a totally new European context.

Naoto: Urushi isn’t just for artistic pieces; it has practical applications in construction and furniture. However, when applied to wood, it doesn’t last indefinitely. It acts as a protective layer, similar to lacquer, but it’s entirely natural. As we move forward, there seems to be a trend towards using more natural coatings instead of synthetic ones.

Naoto: How do you procure Urushi in The Netherlands?

Pao: [Laughs] That’s a challenge in itself. Fortunately, I have connections in Taiwan, who liaise with contacts in Japan. They ship the Urushi to Taiwan, from where it then makes its way to The Netherlands. I’m lucky to have such supportive friends.

Lise: Pao, considering your solo show at Spazio Nobile, there’s been interest in incorporating themes from the Lunar Calendar, particularly the concept of the 24 Seasons. Naoto, do you ever intertwine this with your work or life?

Naoto: The notion that humans are a part of nature is encapsulated in calendars, whether lunar or modern. They significantly influence our psyche and daily rhythms. Although it might seem tangential to today’s topic, I feel that modern humans often forget their intrinsic connection to nature, focusing more on individualism and detachment. By embracing nature, we can use its resources more sustainably without waste. It’s crucial to discern what truly matters and create beauty from that foundation in our lives.

Lise: Pao has now established herself in Eindhoven, in the Western world. Given her research-based work that’s deeply rooted in Asian culture, what advice would you offer her about reintroducing this work to Asia? How can she convey its beauty and essence back to its origins?

Naoto: Absolutely. This trend of blending cultures is already evident globally. I’ve designed a considerable amount of wooden furniture, notably chairs, which we export to Europe, primarily through The Netherlands. Sometimes, distributors inquire whether we utilize local materials or import them. When we mention that our wood is sourced internationally, certain distributors express a preference for local materials. This sentiment is quite prominent, and it’s not exclusive to furniture – it’s seen in traditional crafts like Urushi as well.

For Pao, being in the Netherlands and drawing upon her Asian material culture provides a unique opportunity. It allows her to reimagine – and “imagine” something new. In ancient cultures, the sum of experiences and influences doesn’t simply add up; it multiplies. Pao’s potential lies in her ability to expand her imagination beyond traditional boundaries.

Pao Hui Kao, 25 Seasons, Solo Show, Spazio Nobile, Brussels, Belgium, 23.11.2024–17.3.2024

@paohuikao

www.paohuikao.com

@spazionobilegallery

www.spazionobile.com

www.naotofukasawa.com

@naoto_fukasawa_design_ltd