Description

Les paysages, des espaces vivants reliant le monde visible et invisible

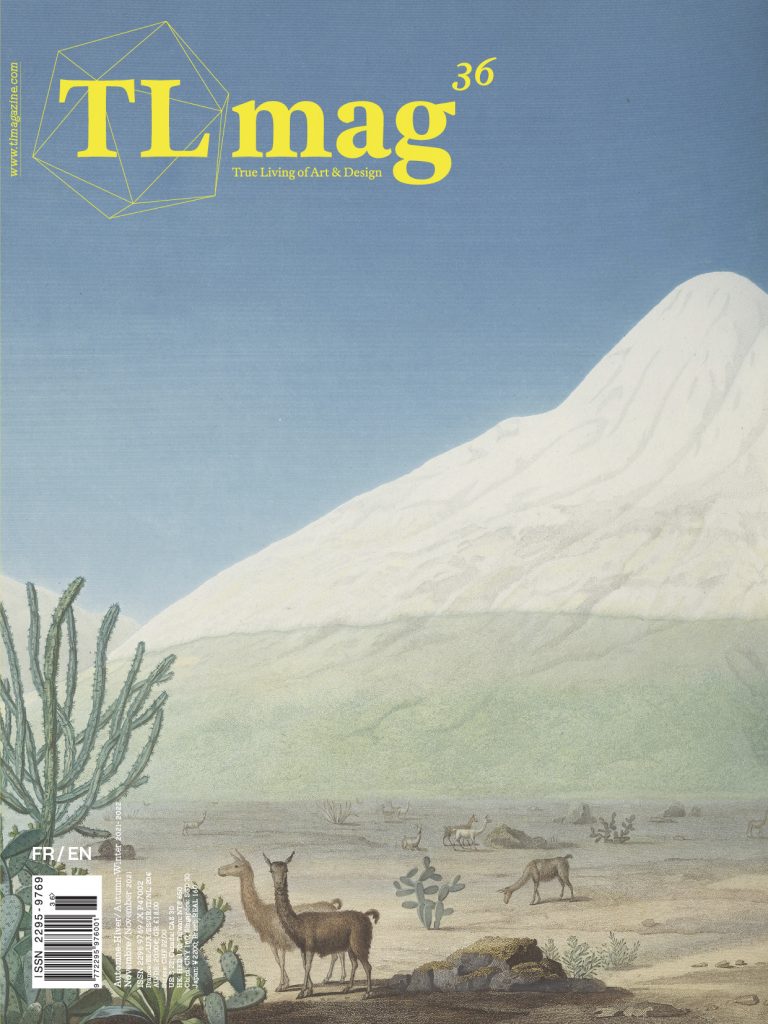

Il n’existe pas de « no man’s land » mais des paysages, que ce soit en Orient ou en Occident. L’artiste Giuseppe Penone parle « des pas qui en foulant le sol créent le jardin des existences. » La notion de Vide et de Plein est présente dans les deux cultures mais se matérialise sous des formes distinctes, tel un cadre de verdure en arrière-plan chez les peintres occidentaux ou un trait de pinceau marquant un souffle qui figure le mouvement ou le changement dans les arts d’Extrême- Orient. La réalité spatio-temporelle y est en outre très différente. Dans les anciens Pays-Bas, les peintres imaginaient des paysages sur la toile dès les XV-XVIe siècles, projetant des scènes d’utopies bucoliques ou l’existence d’un paradis terrestre. Leurs paysages étaient des voyages imaginaires dans des contrées lointaines à une époque où la mobilité n’était pas la nôtre. Les « jardins de l’âme » étaient au coeur de la culture et des beaux-arts du Moyen Âge et de la Renaissance au reflet d’une croyance en un paysage sacré ou l’allégorie d’un verger spirituel. En Orient, le langage pictural embrassait plus librement le paysage avec un empire des signes s’exprimant dans des traits calligraphiques et espacés, révélant la rotation des saisons et le rythme de l’homme et de la nature. Cette dynamique du trait remontant à l’Empire chinois du début du premier millénaire, intrinsèquement liée aux éléments de la nature, y est source d’énergie et de vitalité. Dans cette édition de TLmag, les paysages qui s’ouvrent à nous au fil de ces pages sont le fruit de témoignages de grands penseurs, artistes et paysagistes et visionnaires d’une terre en mutation. La question de la genèse du jardin de l’homme, de son genius loci est au coeur de cette édition bi-annuelle dirigée avec l’architecte de paysage Bas Smets qui s’y est engagé avec ferveur et enthousiasme. Le mystère et l’identité de la vie, l’enchantement du bois sacré ou du temple de la nature font partie de cette quête de compréhension de nous-mêmes et de notre monde en devenir. L’osmose avec le paysage, l’attrait des couleurs et de la matière, la conscience et l’acceptation de notre fragilité pourraient nous guider vers une vie meilleure si seulement nous écoutions encore mieux la terre et la force de ses éléments.

Landscapes, living spaces connecting the visible and invisible world

There is no, “no man’s land”, but there are landscapes, in both the East and West. Artist Giuseppe Penone speaks about “the footsteps which, by treading the ground, create the garden of existences”. The concept of Empty and Full is present in both cultures, but materialises in distinct forms, such as a green background for Western painters or a brushstroke marking a breath to represent movement or change in Asian art. The spatial-temporal reality is very different, as well. In the former Low Countries, painters created landscapes on canvas as early as the 15th-16th centuries, projecting scenes of bucolic utopias or the existence of an earthly paradise. Their landscapes were imaginary journeys to distant lands at a time when mobility was not a reality. “Gardens of the soul” were central to medieval and Renaissance culture and fine arts, reflecting a belief in a sacred landscape or the allegory of a spiritual orchard. In Asia, the pictorial language embraced the landscape more freely, with an empire of signs expressed in calligraphic and spaced strokes, revealing the turning of the seasons and the rhythms of man and nature. This dynamic, dating back to the Chinese Empire at the start of the first millennium, intrinsically linked to the elements of nature, offers a source of energy and vitality. In this edition of TLmag, the landscapes that open to us throughout these pages reflect the testimonies of great thinkers, artists and landscapers, and visionaries of a changing Earth. The question of the origin of the garden of man, of its genius loci, is at the heart of this biannual edition, directed with landscape architect Bas Smets, who engaged in it with fervour and enthusiasm. The mystery and identity of life, the enchantment of the sacred grove or the temple of nature are part of this quest to understand ourselves and our world in the making. The osmosis with the landscape, the appeal of colours and materials, the awareness and acceptance of our fragility, could guide us towards a better life, if only we listened even more closely to the Earth and the strength of its elements.

Lise Coirier, Publisher & Editor-In-Chief TLmag

_

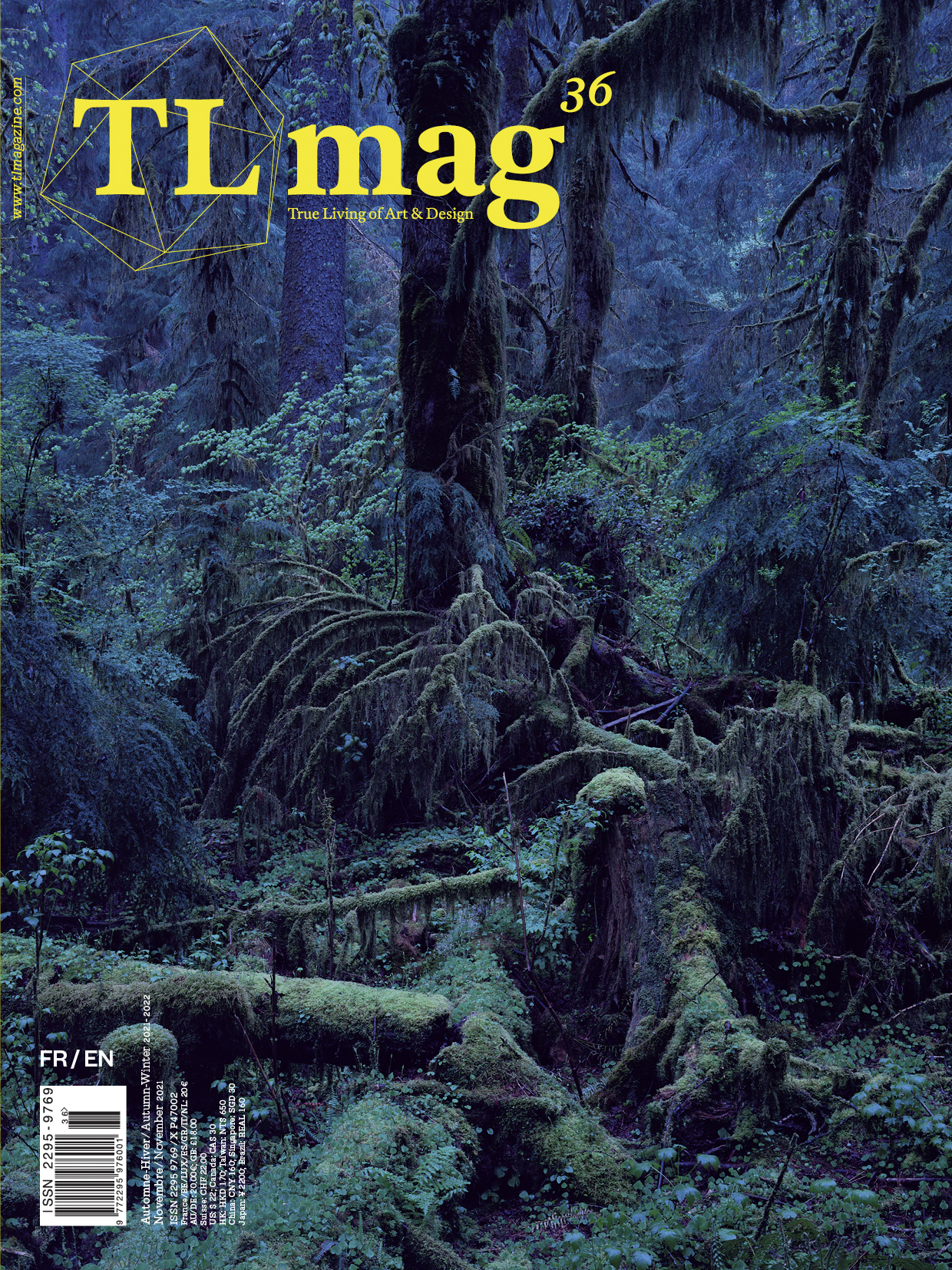

Tout est Paysage

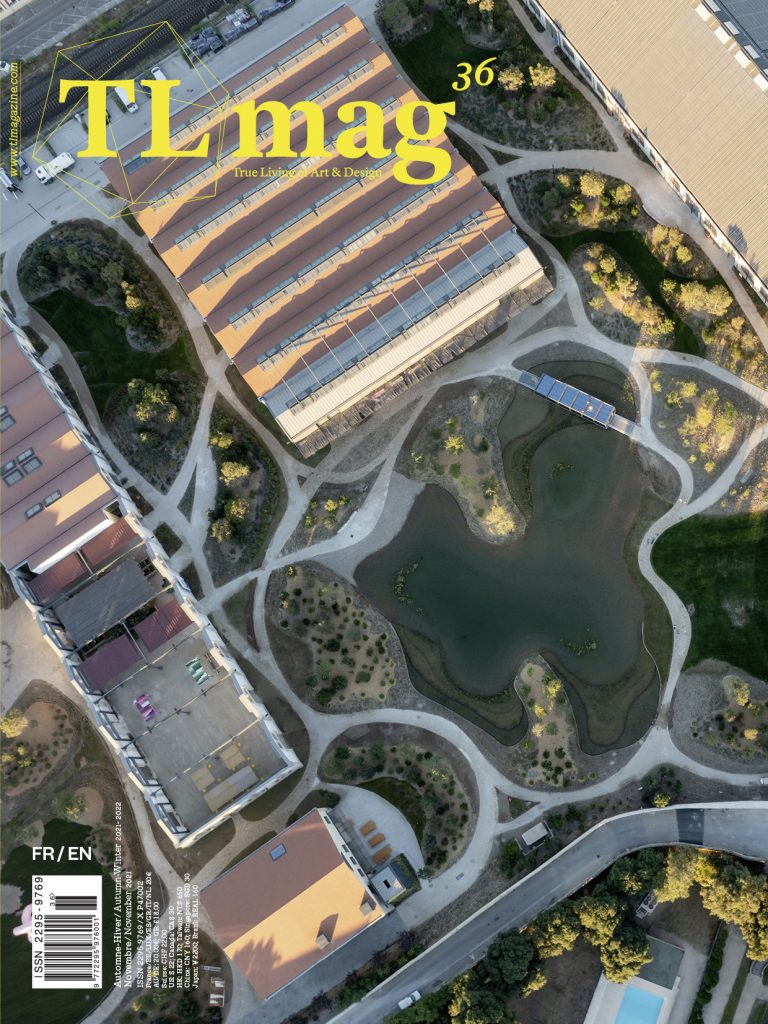

Ces dernières années, nous avons fait l’expérience en temps réel des conséquences d’une hausse des températures de 1 °C qui s’est traduite par des phénomènes climatiques extrêmes comme des inondations sans précédent et des mégafeux. Selon le GIEC, les dix années à venir vont être cruciales pour limiter la hausse des températures à 1,5 °C. Nous devons repenser en profondeur la manière dont nous habitons cette planète. Je suis convaincu que la notion de paysage nous offre une ressource essentielle pour imaginer de nouvelles façons d’organiser notre existence dans ce monde. D’abord, le paysage est une manière d’imaginer le monde, puis de le réorganiser. Le mot a été inventé au XVIe siècle pour nommer un nouveau genre d’art pictural. Les premiers peintres de paysages ne visaient pas une restitution réaliste de la nature, ils visaient plutôt la représentation d’une réalité idéalisée obtenue par la composition et l’organisation d’éléments naturels. Il faudra attendre le XVIIIe siècle pour que la notion de « paysage » soit utilisée pour décrire la réalité physique, en faisant appel à des concepts provenant de la peinture de paysages. L’architecture paysagiste peut alors être comprise comme la conséquence logique de la peinture de paysage. Elle partage son objectif d’inventer de nouvelles façons d’organiser le monde. Et tandis qu’un tableau dépeint une réalité idéalisée « in visu », l’architecture paysagiste transforme la réalité « in situ ».En tant qu’architecte paysagiste, j’essaie d’imaginer de nouvelles façons d’agencer le territoire qui puissent profiter à toutes les formes de vie. Chaque projet donne lieu à l’invention d’un monde nouveau. La relation avec la science et l’art est cruciale dans ce processus de création. Ensemble avec ma partenaire Éliane Le Roux, qui occupe depuis douze ans la fonction de directrice artistique au sein de mon studio, nous avons créé un univers de références dans lequel nous puisons pour concevoir de nouveaux paysages. En tant que curateur invité de TLmag, j’ai souhaité que ce numéro représente cet univers particulier afin de révéler la capacité du paysage à soutenir l’émergence d’un monde nouveau. Nous avons invité trois philosophes afin qu’ils nous exposent leur point de vue sur le paysage : Alain Roger, François Jullien et Emanuele Coccia. Je me suis entretenu avec Piet Oudolf. Quatre photographes nous présentent différents types de nature : les forêts humides du nord-ouest du Pacif ique de Yoshihiko Ueda, les photographies de la forêt amazonienne de Sebastião Salgado, le pergélisol de Walter Niedermayr et nos paysages belges façonnés par l’homme saisis par l’oeil de Michiel de Cleene. Katrien Lichtert aborde la question de l’invention de la peinture de paysage dans les Pays-Bas historiques, tandis qu’Andrea Wulf écrit sur l’invention de la nature décrite par Alexander von Humboldt. Joelle Zask écrit sur le phénomène récent des mégafeux, et Kathelin Gray nous ramène à l’époque du laboratoire de Biosphère 2 et de ses possibilités de recherches sur le changement climatique. Nous avons également recueilli les contributions de Rei Naito, pour qui le paysage est une scène de vie sur terre, de Roni Horn, Thierry De Cordier, Etel Adnan, Lee Ufan et Rebeca Méndez, qui interagissent avec le paysage sur lequel ils travaillent. Ces contributions, et bien d’autres dans ce numéro, donnent lieu à la création d’un univers d’interdépendances qui explore les possibilités concernant l’état actuel de notre planète, mais aussi son devenir. Tout est paysage.

All Is Landscape

From unprecedented f looding to megafires, we have started to experience in real time, and with increasing regularity, the consequences of a 1° increase in global warming. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the next ten years will be crucial to limit this increase to 1.5°. The only way to achieve this is by radically rethinking the way we inhabit this planet. It is my belief that the notion of ‘landscape’ will be essential in imagining new ways of organising our existence in this world. Landscape has always been about establishing a relationship with the physical reality, about organising the cohabitation of living organisms. Landscape is firstly a way of seeing the world, and secondly a way of reorganising it. The word was invented in the 16th century to name a new genre in painting. The first landscape painters did not aim at a truthful rendering of nature, but rather at depicting an idealised reality through the composition and organisation of natural elements. It was not until the 18th century that the notion of ‘landscape’ was used to describe the physical reality, using concepts derived from landscape painting. Landscape architecture can thus be understood as the logical consequence of landscape painting. It shares its aim to invent new ways of seeing and organising the world. Whereas a painting shows the possibility of an idealised reality, landscape architecture actually transforms the reality on site. The research into the relationship between landscape architecture and art recounts the history of the perception of the world, from an idealised depiction to an on-site transformation of it. As a landscape architect, I try to imagine new ways of transforming the land which will be beneficial to all life forms. Every project invents a whole new world. The relationship with science and art is crucial in this invention. Together with my partner Eliane Le Roux, who has been the artistic director of my office for the last 12 years, we have created a universe of references from which we conceive these new landscapes. As the guest curator of TLmag, I wanted to invite some protagonists of that universe to be a part of this issue. Together they show the possibility of landscape to invent a new world. In these pages, three philosophers speak about landscape from their point of view: Alain Roger explains the processes that transform nature into landscape; François Jullien writes about the invention of landscape in China as a f ield of tension; and Emanuele Coccia defines a landscape as a relationship with all the subjects of nature. In an interview with landscape designer Piet Oudolf we speak about the importance of plants and the way they should be planted. Four photographers reveal different landscapes: From the wet forests of the Pacific Northwest pictured by Yoshihiko Ueda to the Amazon rainforest by Sebastião Salgado, to the permafrost series by Walter Niedermayr and finally our man-made Belgian landscapes captured by Michiel De Cleene. Katrien Lichtert speaks about the invention of landscape paintings in the Low Countries, while Andrea Wulf writes about the invention of nature by Alexander von Humboldt. Joelle Zask writes about the recent phenomenon of megafires, and Kathelin Gray brings us back to the incredible laboratory of Biosphere 2 and its unexploited possibilities to conduct climate change research. There are contributions by the Japanese artist Rei Naito, who imagines a landscape as a scene of life upon earth, by Roni Horn, Lee Ufan, and Rebeca Méndez who all interact directly with the landscapes they work in. These contributions, and many more to be discovered in this issue, create an interrelated universe that explores the possibilities of what our planet is, and more importantly what it could become. All is landscape.