Recomposing the Antique

For TLmag38: Origins, Emanuele Quinz wrote about contemporary artists and designers who are using elements of the past to talk about issues of today.

At the start, it was an avant-garde strategy. From Cubist “papier collé” to Dadaist readymades and assemblages, to Surrealist “symbolic objects” or “objects of affection”, including fragments of everyday life in artistic works served the imperative of the montage, of a contamination between the spaces and times of art and life. When, from beneath the paint layers of a picture, subway tickets or wallpaper cropped up, or within a sculpture, concretions of fabrics or the opaque shine of jewellery or other found objects appeared, these works changed in nature, became hybrids, layered like fossils rescued from a volcano, suggestive like wreck- age rising from the seabed, sumptuous like treasures emerging from a fabulous backdrop.

Later, in the 1950s and 1960s, it was the turn of New Realism and Pop Art to rework such borrowing. While on the one hand, these movements marked the extension of the practices from art to design and architecture, on the other hand, they also contributed to blurring forms, functions, and scales. Then, on the threshold of the 1980s, in a telescoping vertiginous in its extent and audacity, but above all in its claimed indifference to the interplay of differences and the hierarchies of meaning, the post-modern worked a further mutation, by confusing the borders of the high- brow and the lowbrow, the new and the old. Beyond the everyday and the banal, it was the antique and the exotic that were preferred for such borrowing. By including within resolutely modern works such fragments of antiquity, architectural or decorative elements from past centuries, or archaeological re- mains, the objects took on from their conception an antiquated patina, an appearance of ruin. But, while for the avant-gardists the purpose of the heterogeneous montage was to awaken the “demon of analogy,” to work, through the play of frictions and contrasts, through the dives into the subconscious, both individual and collective, the post-modern hybrid presented itself as a protean but vehemently harmless monster, proclaiming the interchangeability and reversibility of each element in an infinite, cold and at the same time pleasurable permutation.

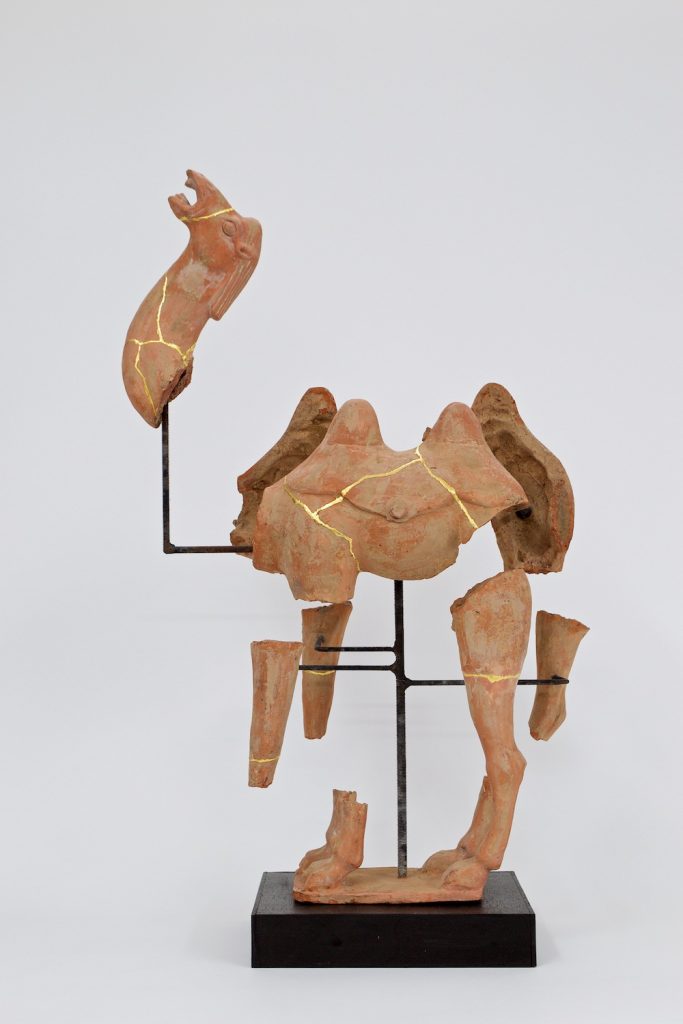

Today, the integration of fragments of antiquity in contemporary works is back in fashion, although adhering to different impulses. In art, one of the most striking — and provocative — examples is the work of Francesco Vezzoli: venturing on the edges between philological respect and kitsch profanation, he covers the immaculate whiteness of dozens of Roman busts with coloured make-up. (Teatro romano, New York, MoMA, 2014–2015). Thus, transformed or, rather, “re- stored” to their original form — because, in antiquity, the busts were brightly coloured rather than white —, these objects denounce our idealisation of the past, our manipulation of history. At the same time, they regain their status as objects of worship, in the secular temple of art. Simultaneously critical devices and playful objects, these works reactivate the ancient fragments not as outdated and inert relics, but as still active, even radioactive, presences, around which rituals are still orchestrated, forces are agitated, mythologies condensed. But it is above all design which, by infiltrating these hybrid objects into our homes, today opens new perspectives for the integration of the antique. First and foremost, contrary to post-modern or neo-baroque appropriation, this integration has absorbed both the conceptual mutation of the arts and the awareness of the ecological and political crises of our present time: recovering fragments of antiquity is an act that stems from artistic institution, but also from a policy of recycling, a criticism of dissipation, overproduction and planned obsolescence, the loss of meaning, the traumas of a world torn by conflict. So, when Bouke de Vries reuses shards of Dutch earthenware, and reassembles them within dazzling sculptures evoking atomic mushrooms, he is playing with the line between ethics and aesthetics, between hope and destruction. And when Sin Ying Cassandra Ho presents her vases (Constructed Realities: Life Beyond Borders, 2022, Nilufar Gallery) on which fragments of ancient porcelain are grafted like organic cuttings of inorganic materials, these objects – more than decorative assemblages or sophisticated trinkets – inhabit the space like half-mineral, half-vegetable excrescences, their skins tattooed with esoteric signs.

Often, the old is subjected to a metamorphosis by a change of material — as in the Textile Ruins (2022) by Sergio Roger, where the marble of busts, statues, columns and capitals has been replaced by fabrics; or in the series of vases by Siba Sahabi (Kerameikos, 2011), where the ceramics and hard stone of Greek, Etruscan or Persian pottery are replaced by paper. In Classicism (2021) by studio Tellurico, the ancient technique of stucco is updated in a performance that melds pieces of a Greek temple in real time in front of the audience. Roberto Sironi, for his part, describes his series Ruins (2021), which combines industrial and ancient elements and materials, as “a collection of contemporary ruins, freely deconstructed and reconstructed, imaginary simulacra, programmed artifices, which become functional to the post- archaeological message conveyed”. In essence, all these design objects, by thwarting the discipline’s industrial and modern tradition, evoke archaeology — but rather an archaeology of the future, where time winds and turns in a spiral, where myth and history, science, and fiction overlap.

Emile de Visscher’s research project, Petrification (2015, in progress) radicalises this vision: through a complex but open manufacturing process, it is now possible to fossilise consumable and fragile materials such as paper. Passing through a 1400 °C oven, delicate objects such as origami are transformed into stone, black as ashes but hard as diamonds. By appropriating this process, other designers compose original col- lections of objects with a timeless appearance. Thus, Grégory Lacoua develops bricks that look like fetishes, while Jenna Kaës, with her passion for medieval imagery, ritual objects, amulets, and sacred vestments, explores the petrification of fabric drapes to make cinerary urns. By playing on the superimpositions of the old and the hypermodern, the conceptual and the ecological, these objects seem to hide an occult dimension that is not only symbolic, but spiritual. Like haunted objects, they condense the memory of a distant time, of an enigmatic origin, which escapes us. Even while keeping the traces of gestures, materials, shapes and symbols of our history, they seem to come from elsewhere. They face us, like totems, which, beyond scrutinising our past, question our future.

www.sibasahabi.com

@sibasahabi

@sinying.ho

@boukedevries

@jennakaes

www.gregorylacoua.com

@gregorylacoua

@edevisscher