Silvano Magnone: Taking Time

Using wet plate collodion photographic processes from the mid-19th century, the intimate portraits taken by Italian photographer Silvano Magnone give shape and feeling to suspended time.

Creating and preparing everything from the chemicals of the image development to the taking of the image itself, one could argue that Silvano Magnone’s photographs are entirely hand-made. Based in Brussels since 2008, the Italian photographer has made it a primary focus in his practice to research and work with alternative photographic processes like wet plate collodion — introducing a placelessness and timelessness to his subject matter. A result of two years of work, his most recent series, ‘DIALOGUES: Memory – Transition – Identity’, harmonises his dedication to these processes with his poetic sensibility. Having recently displayed this work at the historical Brussels building l’Ancienne Nonciature during Spazio Nobile’s group show ‘Le Sacre de la Matière‘, TLmag talked to Silvano about how these analogue processes allow him to stay in contact with his true self, the ritual of taking a portrait and the secret dialogue underneath his new work.

TLmag: I understand that you first started using older photographic techniques a few years ago. What was the inspiration behind or the deciding factor that pushed you to dedicate yourself to using these labour-intensive techniques?

Silvano Magnone (SM): My first encounter with photography was a bit like one of those was a bit like one of those “cliché” stories one often hears about. My father had gifted me his old analogue camera, and as soon as I had gone through the first roll of film I felt attracted to the state in which you are driven as you photograph. It’s a state that requires an unusual amount of concentration, calm, knowledge but also a predisposition to accept the uncertain; the mistake; the “magic”.

The processes I use are slow, organic, unpredictable and above all, they require a very important dose of humbleness. During a darkroom session I feel like I am one of the many elements that allow for the creation of an image. I renounce the position of total control, and the analogue camera allows me to step into a world in which every accident is possible and every unwanted reaction might bring me to see things under perspectives that I would have never imagined. My atelier and my darkroom became a place for creation and meditation. Still today (during the COVID-19 pandemic), or maybe I should say today even more, working with ancient and experimental techniques are fundamental tools to keep contact with my true self.

TLmag: What would you say is the biggest challenge when using (or learning to use) these methods?

SM: One might think that the biggest challenges in learning historical or alternative techniques are to be found on the practical side — but with the internet, it’s become extremely easy to find information and guidance from artist communities in every corner of the world. I think that the biggest challenge in using historical techniques is to find what I like to call the “wow factor”. Living in a world where our eyes are inundated with thousands of images every single moment of the day, I feel the urge to create images that will give to the viewer the possibility to pause and take the time to truly explore and experience in a deeper way. An image created with alternative techniques will certainly stand out as “different” and capture your attention because of that particular look. Beyond its simple appearance, an image should always bring within a profound and meaningful quality.

TLmag: When it comes to using wet plate collodion it seems like the role of the photographer becomes much more than the shooting of the unique image, as you are part of the entire process. During the process of creating an image, is there a moment that stands out for you?

SM: I have always approached photography with the spirit of an artisan. My images are handcrafted: starting from the preparation of the chemistry up until the making of the actual image. Every wet-plate is a unique piece and experience. The imperfections, flaws, scratches, chemical reactions, sometimes even my own fingerprints that are present on the plates, are there to testify the strong bond between me and the images that I craft.

Wet plate collodion requires an enormous preparation, every single ingredient is mixed in my darkroom and every single step of the process requires an incredible amount of attention, cure and precision. Creating a wet plate, when I’m in the right mindset, happens almost like a ritual: every movement, every detail has the same importance as the taking of the image itself. There is a specific moment, though, which stands out every single time. Wet plate collodion is considered a very slow technique because it requires a very long exposure. In order to have a readable image with the natural light entering from the window of my atelier, I often need about 10/15 seconds of exposure, if not more. This is exactly the moment that makes me fall in love with the technique over and over again. When I open the lens and I let the light pass through it, it seems as though time freezes. I often realise that I’m holding my breath, and in general, I find it to be quite an intense and emotional moment for both myself and the subject of the photograph.

TLmag: It seems that you’re especially drawn to photographing people in your studio. What do you think constitutes a “good” portrait?

SM: I’m not sure that I can think about possible standard rules in order to define a good portrait. Rules are not my cup of tea…What I would say is that, in my approach, the most important element is the time. Taking the time to connect with the person I’m portraying is essential to me. Enough time is necessary in order to create a bond, to let the sitter feel comfortable in my studio and to learn to trust one another. For me, creating a portrait is an invitation to a ritual where both parts play an equal and fundamental role.

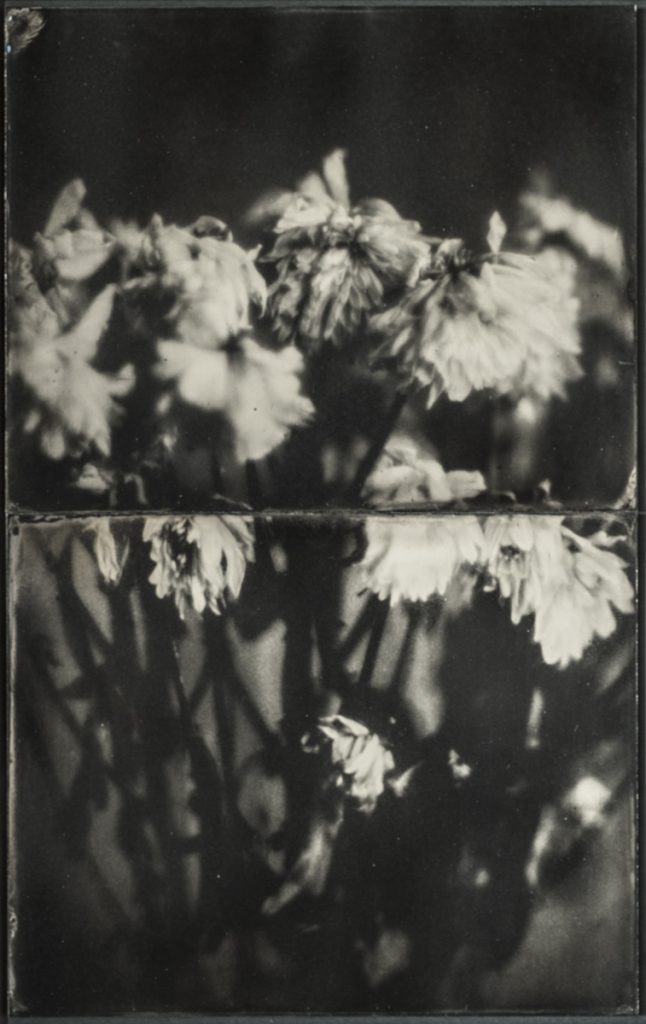

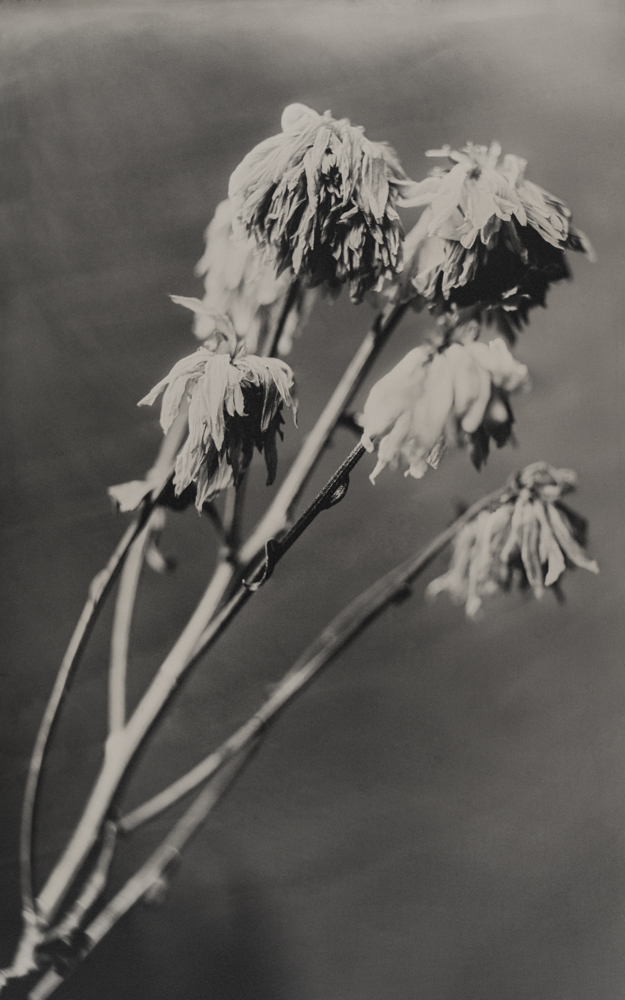

TLmag: Your most recent work, ‘DIALOGUES – Memory/Identity/Transition’, was presented in the group exhibition “Le Sacre de la Matière”. The series juxtaposes subtle and poetic images portraits with equally ethereal images of Chrysanthemums. Could you elaborate on how this work was developed?

SM: I’ve been working on this series for about two years now, and consider it a first chapter of am ore extensive work that I’m planning to continue in the future.

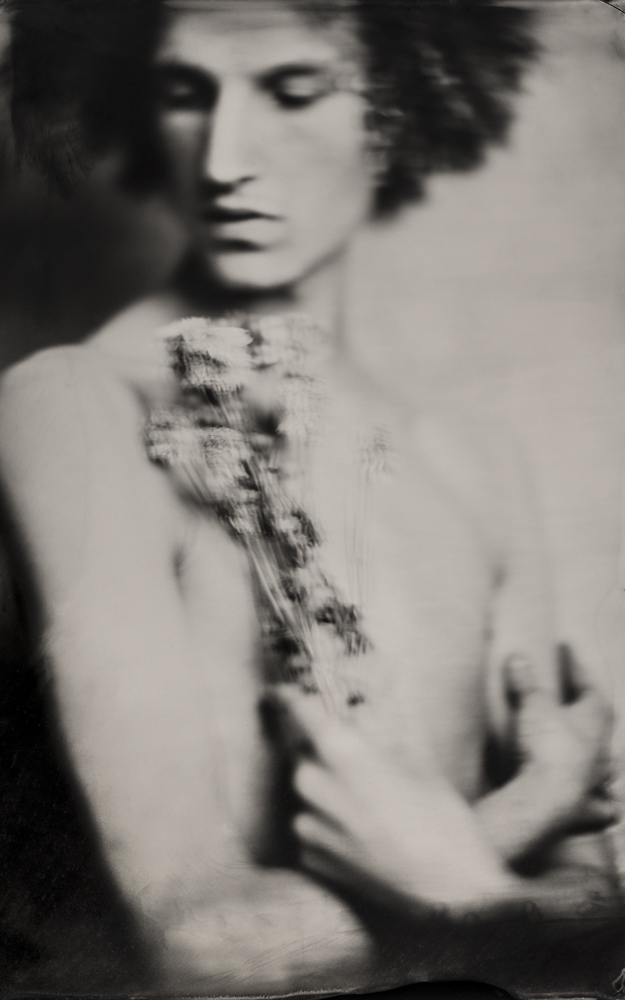

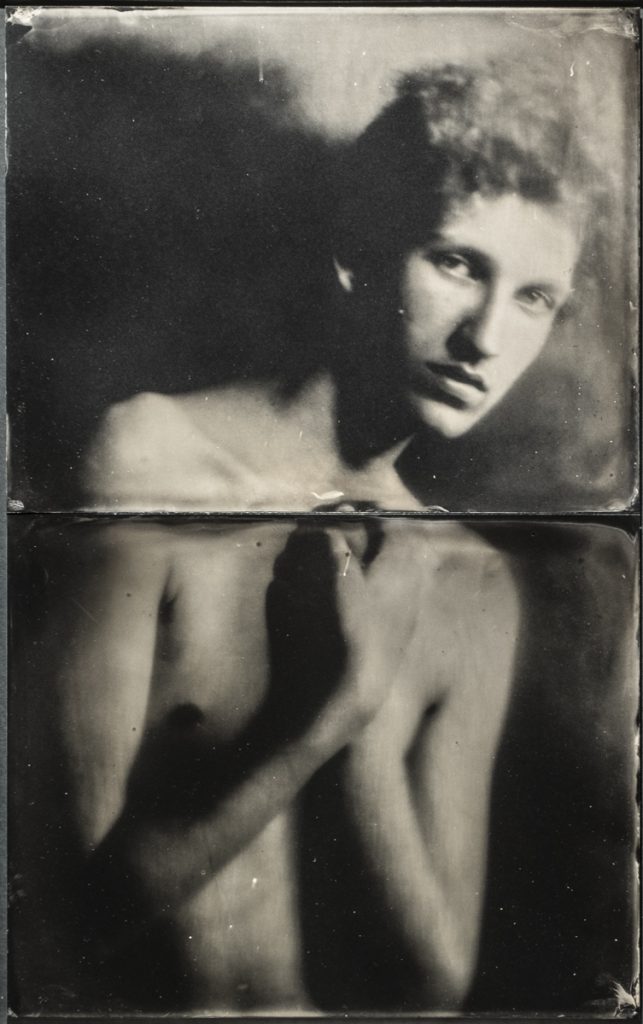

The first actor in this dialogue is a dancer and model called Thomas. I met him in May 2018, and it was one of those meetings that I will never forget. The initial idea was to work with him for a series of nudes that I had been thinking about making for quite a while. I was fascinated by the fragility of his forms: the gracious movement that only the body of a dancer can have. It didn’t take long before I realised that this wouldn’t be a one-time thing. As I started photographing him, I immediately felt that there was a story waiting to be told. What started with a simple coffee turned into endless coffee dates and full meals shared between us. I learnt that he had started to question his own identity, and was scared of the pain that the answers to these questions would cause him. Working through his fear, he was still accepting of the journey he was on — and he was constantly walking this very delicate balance between fear and courage. On the other side of the lens, I was going through my own personal struggle. Big changes were happening in my personal and professional life and even bigger challenges were waiting for me. I had the feeling that using my art and craft to tell his story could help me to understand and accept my own struggles.

At the same time, I had bought and started to take portraits of a bouquet of Chrysanthemums. I loved the fact that, in our culture, these plants symbolise death — while in other cultures they are associated with life. With each passing day, I witnessed how they would get older and drier, and I would fall in love with them a bit more as I portrayed their balance between resilience and resistance. It might sound strange or inappropriate to call those images portraits, but that’s exactly what it felt I was doing when I photographed them. In this long, two year period — I had been meeting and photographing Thomas while observing and photographing my flowers. The longer it went on, the more I realised how these two realities were strongly connected. It is as though they entered into a secret dialogue on and of their own. Together, I feel that they show a profound, timeless dialogue between Nature and Man, Feminine and Masculine, the Ephemeral and the Eternal.

TLmag: Presented in the historic building of Ancienne Nonciature, the series and their frames seem timeless: as much from this time as from the past. Could you elaborate on how you play with the placeless-ness and timelessness in your practice?

SM: It’s undeniable that the aura of the ancient chapel and the cave where the wet plates are installed intensify and brings a deeper sense to the rituality and timelessness of my work. For this presentation of Dialogues, I created a series of images that are divided into 2 to 3 plates. The full, final image shows a very strong cut in the middle of it. Sometimes very organic, sometimes with a stronger presence, these fragmentations of the plates together with all the other flaws and artefacts, are a constant reminder of the necessity of accepting imperfection and the importance of being aware and grateful of the cracks and flaws that contribute to the making of our identity. Similarly, the choice to present the wet plates in old fashioned wooden frames is a way to evoke a sacred dimension and to reinforce a feeling of rituality in my work. The delicate equilibrium between the first impression of a work coming from a bygone era and the actual subject matter creates a tension that accompanies the viewer to witness a timeless rite of passage.

Spazio Nobile’s group exhibition, ‘Le Sacre de la Matière‘ at l’Ancienne Nonciature (Grand Sablon, Brussels) will be on show until the summer of 2020. Yen-An Chen Studio recently made a video to show the exhibition, which you can see here.

Cover Photo: Silvano Magnone by Emanuele Passarelli