The Way Beyond Art at the Van Abbemuseum

The Eindhoven museum presents a new sprawling exhibition featuring its own collection. Curators Christiane Berndes and Steven ten Thije discuss the role of its other custodian: the community.

The first piece one sees when entering the space of The Way Beyond Art, a new exhibition at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, is Anselm Kiefer’s large Varus. The history of Germany is condensed in his painting of the Teutoburg Forest, where the Hermannsschlacht took place between the Roman and Germanic tribes. “It could be considered the moment when the German identity was born,” says Christiane Berndes, one of the exhibition’s in-house curators. “It was a controversial painting, because German identity came with a sense of guilt after WWII, but [in 1976] he wanted to tell people that they could look at the past and also be proud of it.” Right opposite is the print work of Jan Vercruysse, a Belgian artist. “He uses the land not to talk about history, but he proposes foliage, labyrinths where you can walk around and do nothing, using nature in a controlled way to amuse yourself. These are two different ways of using landscape to present an idea.”

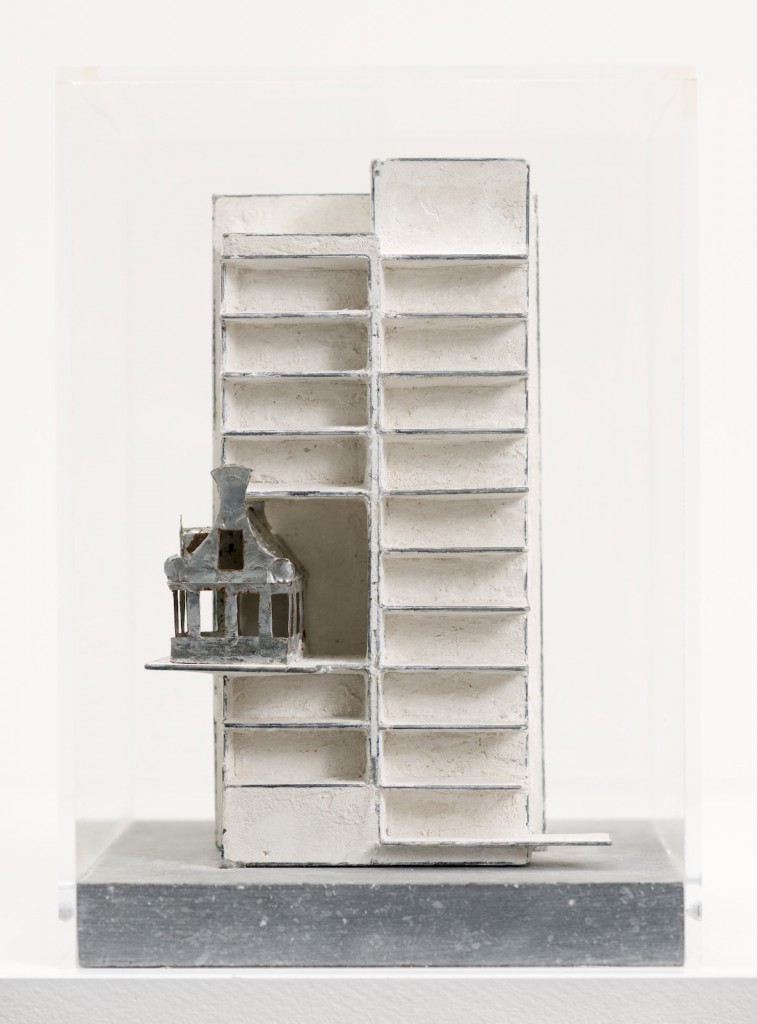

This type of connection, not easy to detect at first sight but ultimately rewarding, is present in a large part of the works the curators have coupled together throughout the exhibition, grouped under the topics of Land, Work and Home. Some, like Kiefer’s piece, address the issue of identity, while others speak of sameness in spite of division —like Füsun Onur’s Let’s Meet at the Orient, where she points her finger at international borders. Others question private space and public rights, familiarity and objectiveness.

The presentation of these works, part of the museum’s own collection, falls under the umbrella of the teachings of Alexander Dorner, who authored the 1947 book that names the exhibition. In it, the German art historian proposed using visual testimonies to understand all three tenses of our time. “He thought that the traditional museum, with its collection of history of art arriving at the ideal shapes, was no longer appropriate for the times,” explained Steven ten Thije, the exhibition’s co-curator. With today’s currency in mind, the duo and director Charles Esche are now requesting input from a fourth curator: the city itself.

TLmag: You have a few empty boards in the panels, throughout the exhibition. What are they for?

Christiane Berndes: They’re asking visitors to leave a keyword about the artwork for the next visitor. People like to leave something in the galleries. It’s a very personal sign that you leave behind, and for other visitors it’s very nice to read to read the response of the previous visitors. It creates a kind of hospitality and togetherness amongst the visitors. They feel welcome to have their own opinion: sometimes the keywords are very simple, but it makes the distance between the artwork and the visitors smaller.

We tried it a couple of years ago with a project from Superflex, but we learned that one keyword is a bit limited, so we wanted to make it a little bit broader. We are now giving their visitors the possibility to publish their opinions.

TLmag: Why are you so interested, as a museum, to tap into the community’s thoughts?

Steven ten Thije: We started to become more aware of our gatekeeper role, and we needed to share that role in order for the museum to live up to our idea of an inclusive society. In the beginning, it was more the idea that we had something beautiful and wanted to share it with people, and we tried to find ways in which they could enter into a dialogue with us —the text was one way and the viewing depot, a place where people could request a work and put it up themselves, was another. In the last years this discussion has gotten a new intensity because now we’re more aware of the necessity for a public museum to have a platform for different community voices. As much as we would like to represent everybody, we are not, so we need to be able to find a way to give a platform to the voices that are different from ours. Instead of trying to talk about people, we need to find a way to talk with them, first. That’s our new process. We try to create a situation where it’s not about “this is the collection and this is what it means,” but instead we try to create a structure in which it’s up to the dialogue between us and the community. That’s why the installation design here is quite flexible and modular, so you can easily change things in many different ways.

We need to find the format in which this become more or less normal for the museum. Either we have an immensely diverse staff or we need to find a way in which different people can express themselves. We are primarily funded by the city and, in a way, want to give new meaning to the request of the city: “How can this be our museum?”

TLmag: How did you settle on Land, Home and Work as main themes for this exhibition?

CB: We asked ourselves: “Which topics would be of importance for everyone?” Land, labour and home, which are important to all of us, are addressed in a lot of artworks. We made a selection with these three categories in our minds, and they are presented here to try and inspire people to bring up specific questions that they have about these topics.

We have a series of prints commissioned by the Dutch government in the 70s and 80s to honour the Deltawerken, the plans to defend the country against water. We [the Dutch] seem to be quite well known for that. We’ve never shown these works before; they’re a kind of advertisement for Dutch technology, and a topic that also refers to global warming today. This also addresses the function of art: in that period, the Dutch government used art to communicate to people to feel proud of the Netherlands. Would that happen today?

TLmag: Why wouldn’t that happen today?

CB: There is this notion of the autonomous artist, not the artist that works by commission. It tells something about the position of art and the artist, but also about identity.

TLmag: You mentioned that the exhibition design is flexible, to allow for constant change in the selection of works on display.

CB: We worked with Can and Asli Altay, from Future Anecdotes Istanbul, and we tried to challenge the borders between the curators, the artists and the exhibition designers. We had worked with them on another exhibition in the [Van Abbe] tower, and I knew that they were very interested in public space in architecture.

STT: Also, they had experience working with community projects before.

CB: We started with the modern grid but we also go against it. We asked ourselves: “How can we demodernise?” So we made clusters out of the structure, taking parts out, and they put it diagonally against the gallery space. He addresses the tension of the modern and the gallery room. We’re trying to cross borders and open ourselves to new ideas of both art and exhibition design.

TLmag: It’s not a physically comfortable feeling. It’s not an easy exhibition, actually. On my first visit, I didn’t know if I was allowed to cross the carpet inside one of the installations.

CB: It depends on your expectations, your conditioning. We have children who’ve really enjoyed it, because they’re not conditioned to not touch things inside a museum. It addresses the conditioning that we have created together —as children, we start hating the museum because we’re not allowed to touch. We want to move from the disembodied spectator of the white cube to a… bodied spectator. Experiencing the art also has to do with moving, maybe touching, maybe writing. We tried to welcome the whole body, and that can feel uncomfortable. There is no sign that says “yes, you can cross this carpet.”

The Way Beyond Art is open, and constantly changing, until January 3, 2021.