Lennart Booij: Dream Out Loud

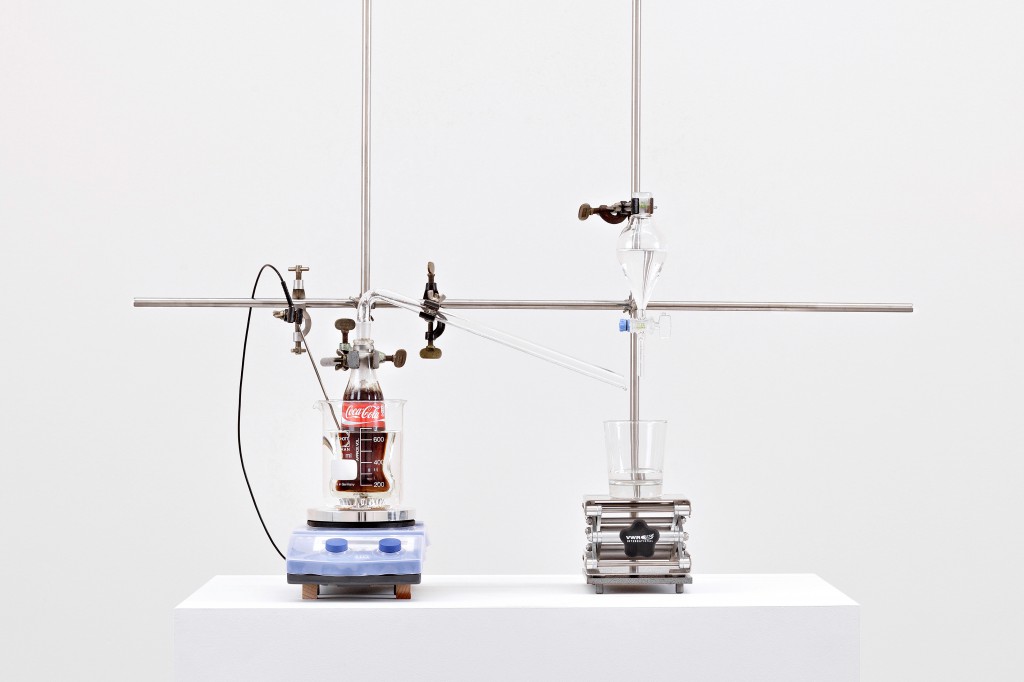

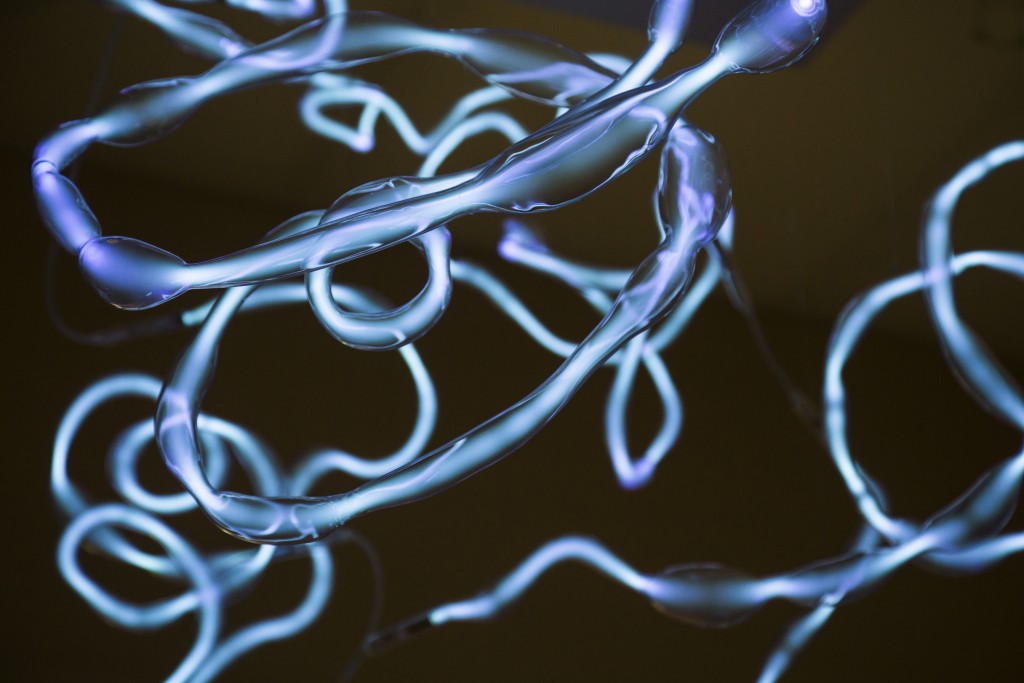

What is the role of design? The question continuously plagues academic and commercial discussions the world over. However valuable for the evolution of such a volatile discipline, many of these ambiguous debates fail to root their arguments in the relevance of widespread application, practicality or current issues. In many cases, such gatherings become platforms for mental appeasement, mired in recounts of process, aesthetic description, anecdotal storytelling and self-affirmation. In an attempt to simultaneously adopt and critique this condition, Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum mounts the Dream Out Loud exhibition (till 1 January 2017). Unashamedly, the showcase of contemporary Dutch ‘social design’ – in 26 varied iterations – returns to an almost Modernist idealism, offering up optimistic and viable answers to some of the most troubling problems of today and tomorrow. Pieter Stoutjesdijks’ Shelter for Haiti – an easily assembled housing parameter that employs local materials – joins less literal projects like Bart Hess’ Digital Artifacts ‘performance.’ Questions of craft and technology, social unrest and ecological disaster still translate through the content and shape of speculative design. However, things have evolved from the days of burning design classics that only achieve ironic and self-referential commentary. Dream Out Loud demonstrates how the conceptual prototypes that made Dutch design so famous two decades ago can actually transform into viable solutions for a better world. Much of the underlining themes of value have withstood the test of time but are now joined by new modes of thinking and form-giving. Curator Lennart Booij makes his case.

TLmag: The Dream Out Loud exhibition seems to have pinpointed the zeitgeist of Dutch design; both in its output and in the critical engagement of different actors involved in its evolution. Explain how this nation-based movement has veered away from the humouristic, at times conceptual and expressive, reconfigurations of existing archetypes – associated with late Postmodernism – into projects that readdress the socially and environmentally-conscious foundations of the discipline.

Lennart Booij: The economic doom and gloom of the 2008-2012 period impacted academies and design lectures. Richard Sennett’s The Craftsman did its share to re-position the designer as maker and producer; addressing the responsibilities that come with this role. This allowed a new generation of Dutch designers to become more conscious of the capitalist system they were working in; the responsibilities and choices they had herein. The design field in the Netherlands has since broadened. Many practitioners now cooperate with scientists, researchers and philosophers. As the country is quite small and relatively open on a social level, these connections are made quite easily. This has led to a new approach with different types of actors and results.

TLmag: In their recent Beyond the New manifesto, Hella Jongerius and Louise Schouwenberg called for realigned definitions, separating art and design. Does the speculative treatment of contemporary design – a condition first employed by the poststructuralists and the Radical Italian Design movement – remain a means to provocation, communicating awareness, rather than just shaping practical solutions? Should a design still enter the marketplace if it is to have social or sustainable resonance in the long term? Can such a design ever truly achieve mass dissemination other than in a trickle-down model or in large museum visitor numbers? Is there potential for transcendence?

L.B.: This question is indeed quite historic. In my opinion, designers cannot live without prototypes, research and gestures. But in the end, they all have to answer the question of which way their work leads to improvements in sustainability and function. Agatha Haines’ Circumventive Organs remains fictional but opens up an ethical debate, questioning whether or not we are on the eve of redesigning and improving into a sort of mankind 2.0. Her work provokes discussion amongst designers and ethical thinkers alike. In this case, we might better speak of designer scouts; on the lookout for new combinations, new fields of research and design. So far, such projects have been labelled as bio-design, social design or experimental design. But much of these practitioners started out by working for companies, with investors and/or start-ups.

I believe that design gestures and prototypes, found in museums eventually find their way into the real world. Look at the Fairphone, The Current Window by Marjan van Aubel or Dirk van der Kooij’s chairs. They are all for sale on the open market. It rather raises the question what we as consumers will decide to buy in the future. Will we stick to low-end IKEA solutions or are will we be willing to invest in more high-end quality products, that stick around for longer. It also provokes big brands like Apple to consider why they don’t invest in sustainable chains for their products, pay equal wages and help save the environment. I think the impact of these new Dutch designers lies not only in product design but also in mental and moral attitudes; how companies and designers fulfil their social responsibility.

TLmag: In either influencing awareness or finding viable solutions, are the social and environmental issues addressed by the various projects on show intrinsically linked? In such an increasingly ambiguous and pluralistic global context, how are these designers able to adopt positivistic stances as manifest in their work?

L.B.: First of all, they are all profoundly optimistic. There’s a belief that by choosing the right materials, the right forms and manufacturing methods, a better and more sustainable product can be made. However, it’s not simple to turn and twist current economic programs and systems. Solutions need to begin on a small scale. I see this happening in diverse places around the world. Even in China, sustainability has now become a key issue. We can perceive the revival of local craftwork from Brooklyn to Italy and beyond. It all starts with the attitude of dreaming out loud. To me, Boyan Slat, who has developed a new way to remove plastic waste from our oceans, is the best example of how what starts locally can become a global effort.

TLmag: In your curatorial essay, you reference both Papanek’s environmental pragmatism and the craft-based methodologies formulated by Sennett. In considering the group of talents and practices on show, should designers continue on the track of relinking the once disjointed role of craft and design in guiding debate and forming solutions for a better world?

L.B.: Well, both Papanek and Sennett raise the question of time and attention a person should take to become a good craftsman or designer. To me this is the underlying current of the show; time and attention. This is the most scarce resource we seem to have, but because of automation, robotisation and the ending of the machine-age, we will hopefully win back this condition. This opens up new awareness regarding forms, products and processes. This trend is linked to new possibilities of owning your own machines (robot-arms/3d printers or laser cutters) to act as both designer and producer.

TLmag: On a curatorial level, did you choose to break the mould of traditional exhibition formats – employing an almost praxis-based approach that could echo the discursive nature of the work on show – or did you rely on the established framework as an almost recognisable medium-cum-blank-slate to offer the public an easier way in? Describe your intended impact.

L.B.: In the beginning, my thought was to break the mould as it would have fit so well in presenting the group of work on show. But later on, I realised that we also had to win the hearts and minds of our visitors and therefore finally chose an ephemeral white cube model for both the scenography and signage. Show-designer Bart Guldemond did a tremendous job to build simple pedestals which seem to come out of the wall as drawers and graphic designer Joost Grootens made a beautiful grid-scheme based on a line in a greying field. Under this line, one finds the text. The space above the line remains empty as to symbolise the mind and dreamt space.

Dream Out Loud

till 1 January 2017

Stedelijk Museum

Museumplein 10

Amsterdam, Netherlands