Jorge Penadés: The Skin He Lives in

With this latest project, the leather-repurposing Poli-Piel, the Spanish creator does circular design the Madrid way

There’s something moving in Madrid. Just ask Málaga-born designer Jorge Penadés, who’s been calling the Spanish capital his home for the past four years. After roving through Barcelona, Eindhoven and Oxford, there’s a reason he’s set base in the city. Several, actually.

The way he sees it, 2018 has all the makings of a perfect storm for the local design community. For starters, there’s the so-called Carmena effect: the first leftist mayor of the city in 24 years, Manuela Carmena, has been an avid supporter of the arts sector —just a few days ago, she made headlines for boycotting ARCO due to the purported censorship of a politically tinged set of photographs by Santiago Sierra. In 2016, still licking their wounds due to the effects of the devastating economic crisis, 25.9 percent of madrileños complained about the lack of job opportunities; in 2017, according to data from the city hall, it’s only a large cause for concern for 9.7 percent of them. If you want to see those numbers converted into actual activity, just watch the sheer rising speed of creative SMEs and their storefronts around the bustling neighbourhoods of Malasaña, Chueca and Chamberí.

As a further testament to this growth, this month the city had its first major event for the niche: the Madrid Design Festival, with close to 50 exhibitions in more than 30 sites spread throughout the capital and a roster of nearly 60 talks and workshops headlined by names like Jasper Morrison and Nacho Carbonell.

That’s where Penadés presented his latest project, Poli-Piel, a sage reimagining of the manufacturing possibilities for leftovers from the local leather industry.

It’s no coincidence that he’s working with a product so intricately linked to Spain. Leather goods are a part of the country’s DNA, and nowhere is this more evident than in the Andalusian town of Ubrique: half of its population is made up of skilled craftsmen and women who provide the handiwork for the likes of Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Comme des Garçons and local star Loewe. Artisanship is alive and well there, hundreds of years after the ascent of the leather guild during Roman times.

Penadés was born some two hours away from Ubrique, in a fishermen’s village up the Andalusian shore. Armed with a degree in experimental design, he was “wearing white COS shirts with black pants, working with light wood and plants all around… and then I had a crisis.” That’s when an epiphany came his way. “Minimalist Scandinavian aesthetics? That’s really cool, but I’m Andalusian! We’re loud, we’re passionate. That’s when I decided to research my roots and use that in my work.”

That meant analysing the things around him, back at home. One of his current furniture projects, Viernes por la tarde, jumps off the use of the Málaga espetos technique for grilling freshly caught sardines with olive wood skewers. Consider the extension of those groves: Andalusia is the world’s largest producer of olive oil, and the once manual harvest is now done by machines that require wide berth. Thus, an increasing amount of trees, randomly “planted” by nature, are pulled out of the ground to be set by tractors in a new grid. The roots they leave behind are commonly destined for the furnace due to their brutal hardness. He’s turning those cuts into stools that see themselves as side tables.

“I know the industry works a certain way, but I’m trying to become an opener of doors: What if we could do things in a different way?” That state of mind comes from, well, just being in Spain. “Those of us who come from Latin cultures, in the Mediterranean or in Latin America, live our lives with a constant component of improvisation,” he explains. “We make do: there’s no [economic] safety net, and that makes you face life, and even the design profession, in a different way. It’s not any better or any worse… it’s just different.”

That means that just executing the idea of circular design, an increasingly widespread concept, doesn’t cut it. Some economically safer countries have the luxury of putting out new products made out of discarded materials, that never quite live to their aesthetic potential nor honour their source. But as a designer who rose from the rubble of the crisis, from a country that sees itself as an underdog compared to its European neighbours, the aim is quite different: the resulting piece has to completely overshadow the beauty of its previous incarnation. He learned to turn trash into gold from “the masters at Studio Swine,” a big influence on his work. Oh, but this version has to proudly shout its origin. Underdog no more.

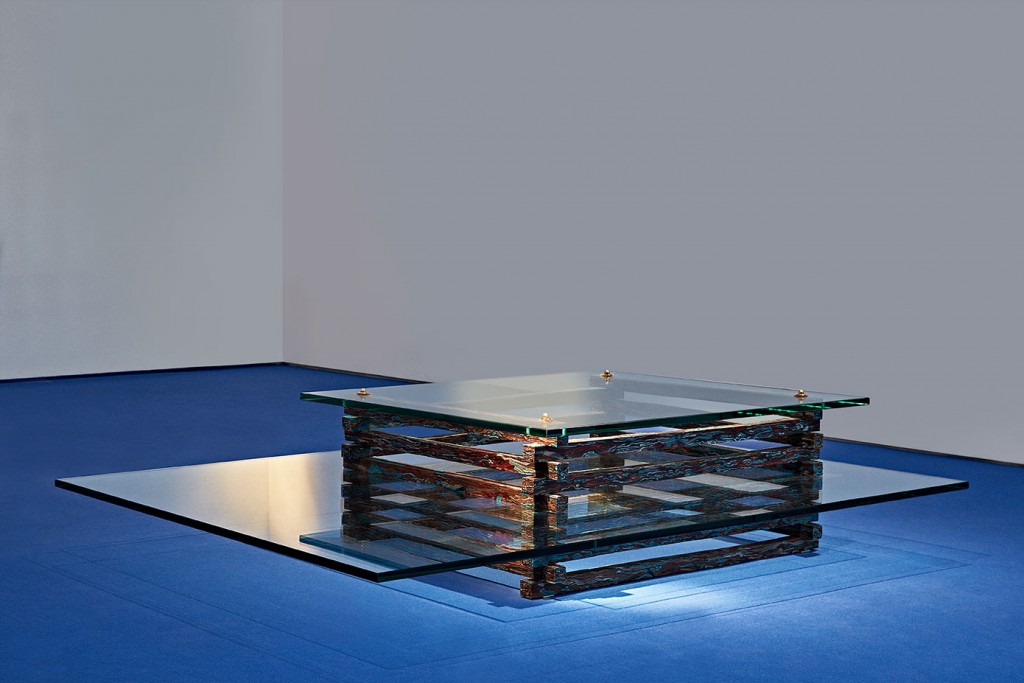

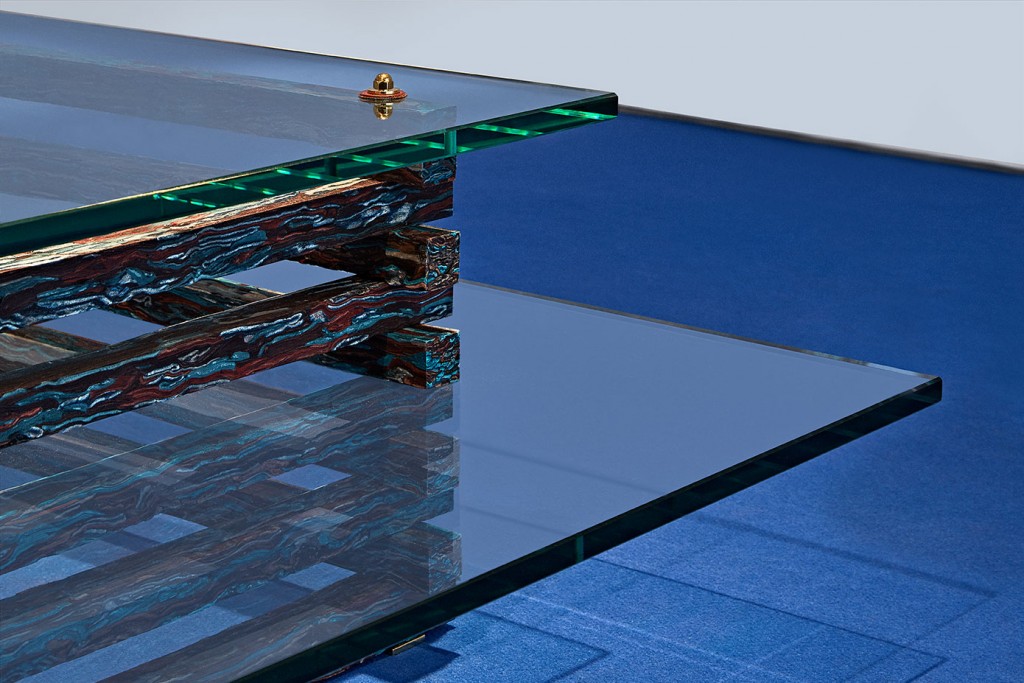

Case in point: Poli-Piel, a set of functional pieces made out of Ubrique leftovers. Take a look at the pictures next to the text in this piece: that’s not wood. Those blocks are made of hundreds of discarded leather bits, organised by colour and intricately stuck together with bovine collagen. Penadés’ grandfather and great-grandfather were cabinetmakers. His father decided to go his own way. “So, in order to honour my grandfather, I decided to make my own wood.” The pieces, though, go beyond their elegance and their trompe-l’oeil quality: by providing movable components, the beauty of his proposed arrangement notwithstanding, the designer has the humility to let the end user hack their way to the final state of his mirror, his chair, his coffee tables.

But Poli-Piel, and one might argue, Jorge himself, only exist due to one of those creative SMEs popping up in Chamberí. Machado-Muñoz is the only designer furniture gallery in the country. For the last few years, the namesake married couple —Gonzalo Machado is a fashion photographer, while Mafalda Muñoz is an interior designer— have been putting their money where their celebrated taste is: they finance the full production costs for the local designers they take under their wing. “I’ve spoken to people overseas who can’t even fathom the relationship Mafalda and Gonzalo have with designers who are just starting their careers,” Penadés muses about his first solo show. “It’s an idyllic situation for a designer. I’ve never met anyone who would risk so much out of passion, who can edit the soul of your work in that way. They were the first to believe in me, and had they not been there, I wouldn’t be a designer today. They’re one of the agents responsible for the synergy in this city that gave way to the first Madrid Design Festival.”

After the political crisis that was the Franco era, the city responded with la movida madrileña, a countercultural movement propelled by economic growth. La movida gave the Spanish-speaking world some of its musical greats, from Alaska to Mecano, and became the inspiration for Pedro Almodóvar’s earlier films. Perhaps the next iteration of a post-crisis cultural scene in the city won’t come in the shape of music and literature, but cloaked in design. “You can definitely tell there’s something going on here nowadays,” concluded Penadés.

There is, indeed, something moving in Madrid.

Poli-Piel is on display at Machado-Muñoz until March 10. This is the first part of our coverage of the 2018 Madrid Design Festival. To read the rest of the series, click here.