Jack Lenor Larsen: In Handwoven Form

It has been nearly 2-years since the passing of legendary textile designer and connoisseur, Jack Lenor Larsen, whose legacy lives on at the LongHouse. For our S/S 2021 issue, Adrian Madlenar wrote about this passionate and endlessly curious artist who helped bring handwoven textiles into the forefront of art, design and manufacturing.

Creative people have attempted to make the critical link between art and industry since the dawn of the modern age. Few have been able to mitigate the systemic effects of increased standardization with individual achievements that could at once push the limitations of convention and still attain broad appeal. Jack Lenor Larsen was one such figure. The maker, entrepreneur, author, educator, and connoisseur’s most recognized contribution was the reintroduction of handweaving techniques to the textile industry. Established in the early 1950s, his eponymous brand put out an endless stream of innovations during its 5-decade run, propelling its founder into becoming one of the most prolific and respected American designers of his time.

And yet, Larsen’s influence on late 20th and early 21st- century design was even more far-reaching. A proponent of craft long before it was trendy, Larsen’s appetite for the handmade took him across the globe. Uncovering both long-forgotten traditional techniques and modern interpretations influenced his practice time and time again. Eventually, this fundamental appreciation shaped his understanding of life as an art form. A metaphysical evocation of weaving itself, the intersectional combination of disparate materials in harmonious blends, LongHouse Reserve is the late talent’s lasting legacy. The meticulously cultivated 6.5-hectare home and art park epitomizes everything he achieved, believed in, and contains the vast array of objects he collected during his long life. Though Larsen passed away at 93 in December 2020, the foundation, located in East Hampton, New York, lives on in his image.

“People refer to Jack as a master of textile design, but he was really a master of life,” Caroline Baumann expresses. The acclaimed design leader and cultural consultant first met Larsen while working at MoMA in the late 1990s. He became a close friend and advisor, especially during her years as the director of the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Baumann chose Larsen as the recipient of the coveted National Design Director’s Award in 2015. “He wasn’t one of those talents who remained in their studios. Jack was constantly out in the world seeking out new creative work and had plenty of opinions to share. He always balanced his candour with kindness and a willingness to share wisdom.”

The Seattle native began by studying architecture at the University of Washington but quickly shifted his focus to interior design and furniture. Discovering ancient Peruvian textiles was the catalyst for his pursuit of the medium. After receiving a master’s degree from the Cranbrook Academy of Art, he moved to New York and established his company. Arriving in the heyday of International Style Modernism, Larsen’s first big break was to create translucent linen and gold metal curtains for SOM’s Lever House building.

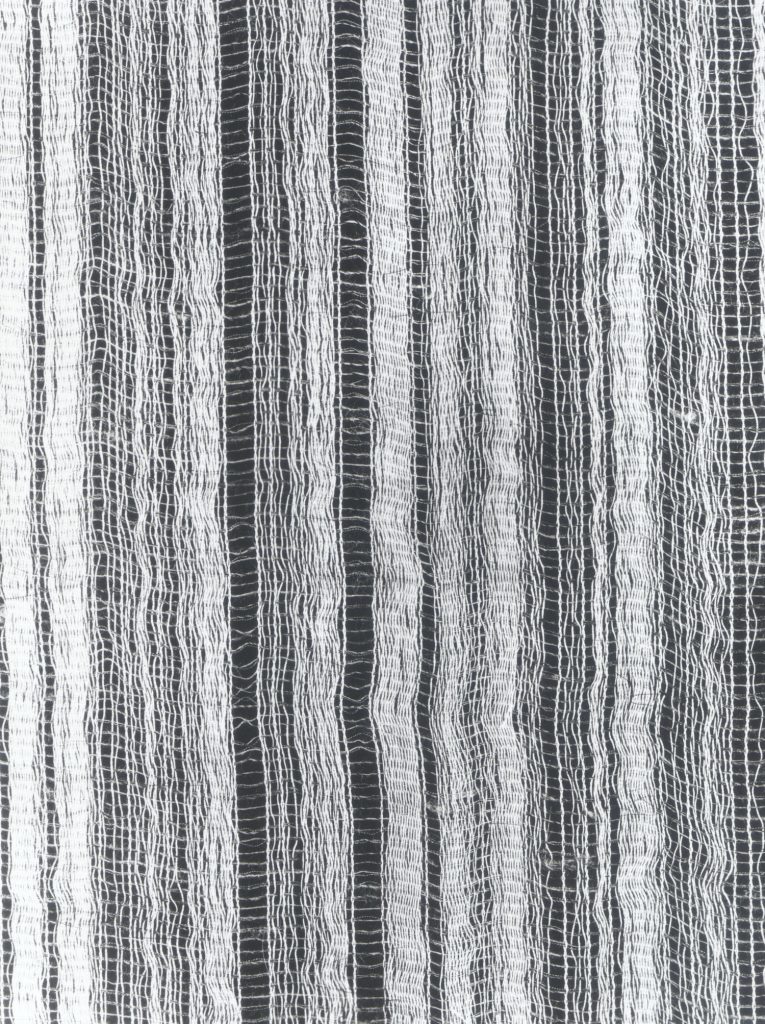

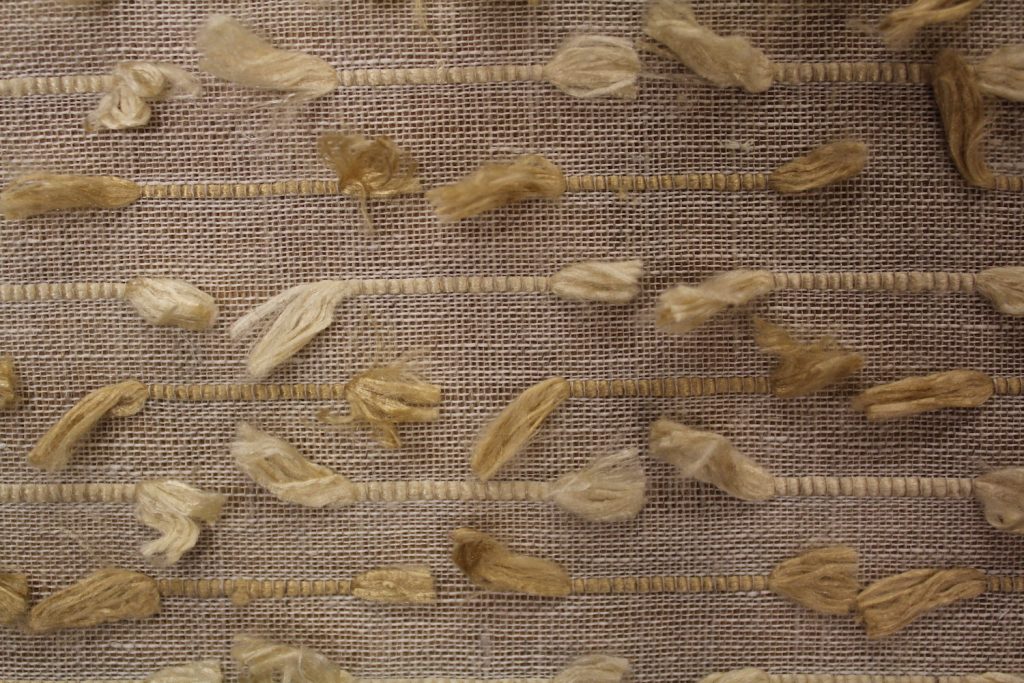

His career quickly took off from there, as did his signature style of handwoven random repeats in variegated colourways. Florence Knoll initially dismissed Larsen’s work as too individualistic but later commissioned him to create olive-green and orange-coloured upholstered fabrics. His textiles soon became the envy of celebrities like Marilyn Monroe and Joan Crawford. In the 1960s, he developed designs for Pan Am Airlines and Braniff. He also worked closely with architects like I. M. Pei and Louis Kahn. Larsen’s brand rapidly expanded across the globe.

“Jack became an entrepreneur at a young age, but It was the combination of passion, business acumen, and the profound understanding that collaboration drives good design that made him so successful,” Baumann explains. “He brought on the right people at the right time who helped to evolve and grow his company and brand.”

Larsen’s recognized aesthetic matured in the 1970s. Influenced by trips to Indonesia, he began to introduce traditional ikat and batik techniques to textiles that seem to emulate the moody and misty landscapes of his native Pacific Northwest. “His evolution was fascinating,” Baumann reflects. “He once referred to his designs from the 1960s as vulgar because of their jarring colour contrasts. But these fabrics are marvellous and part of his creative continuum. You then see him move into what he’s more known for today, the subtle dance of celadon greens and hues that seem impossible to achieve in textile, for example.” By the time Larsen’s first retrospective rolled around at Paris’s Musée des Arts Décoratifs in 1981, he had created 60-thousand designs. He was only able to show 300.

Acquiring land on the East End of Long Island in the mid-1980s, the master engaged in his next big project, a culmination of everything he had achieved in his career and discovered during his travels. LongHouse was established as a case study to exemplify a creative approach to contemporary life and living with art in all of its forms. A 13,000-square-foot Charles Forberg- designed home, inspired by a seventh-century Shinto shrine, anchors a sprawling sculpture garden. This diversely planted park features a Buckminster Fuller- inspired dome, an all-white chess set by Yoko Ono, numerous glass sculptures by Dale Chihuly, and prehistoric totems sourced from throughout the far east. “Jack had an insatiable hunger and curiosity for other cultures,” Baumann reflects. “He was a Japanophile, which was immediately evident in how he dressed and the chosen architecture for LongHouse. A holistic vision and meditative quality are expressed magnificently in his work but also in the objects he collected: bamboo, interlaced baskets, linen, double-weaved boxes, Wharton Esherick gems, ceramics from a dozen cultures and two millennia – it all comes together impeccably and magically at LongHouse.”

LongHouse continues to offer educational programs for people of all ages and is enjoying robust visitation. “Jack’s impact was incredibly wide-reaching. He comes to mind on a regular basis, particularly when I’m appreciating nature or looking at new work in studios and museums.” Baumann concludes. “I think a lot about how contemporary designers are reconsidering their processes right now. Design companies are focused on upcycling and recycling, as they need to be given the climate emergency, but so are independent artists and designers like Liz Collins, Sonia Gomes, Misha Kahn and Fernando Laposse, all of whom are experimenting with different ways of making. Today’s talents are reincorporating craft in their practices and working with all sorts of diverse materials, as did Jack early in his career. He was a pro at experimentation and reinvention, a combination that isn’t easy to accomplish. He was indeed larger than life.”

https://longhouse.org

@longhousereserve