An Epic Journey of Fluctuating Emotion: The art of Ragnar Kjartansson

Ragnar Kjartansson, the Icelandic artist’s performance and video work, mines the experience of monotony with its repetition and a stretched duration.

Siegfried Kracauer is an underrated sage of the twentieth century; overlooked, despite, arguably predicting the information overload we experience in the digital age. Years before ideas on the attention economy gained traction, and decades prior the Internet and mobile technology exacerbated the problem, the German sociologist wrote in 1924 that people living in dense cities or tuning into the radio suffered “permanent receptivity”, producing a middle class “pushed deeper and deeper into the hustle and bustle until eventually they no longer know where their head is.” People were in a state of constant arousal that meant, Herbert A. Simon, the psychologist who would at last bring this thinking into the mainstream in the 1970s, “A dearth of something else: a scarcity of whatever it is that information consumes. What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients.”

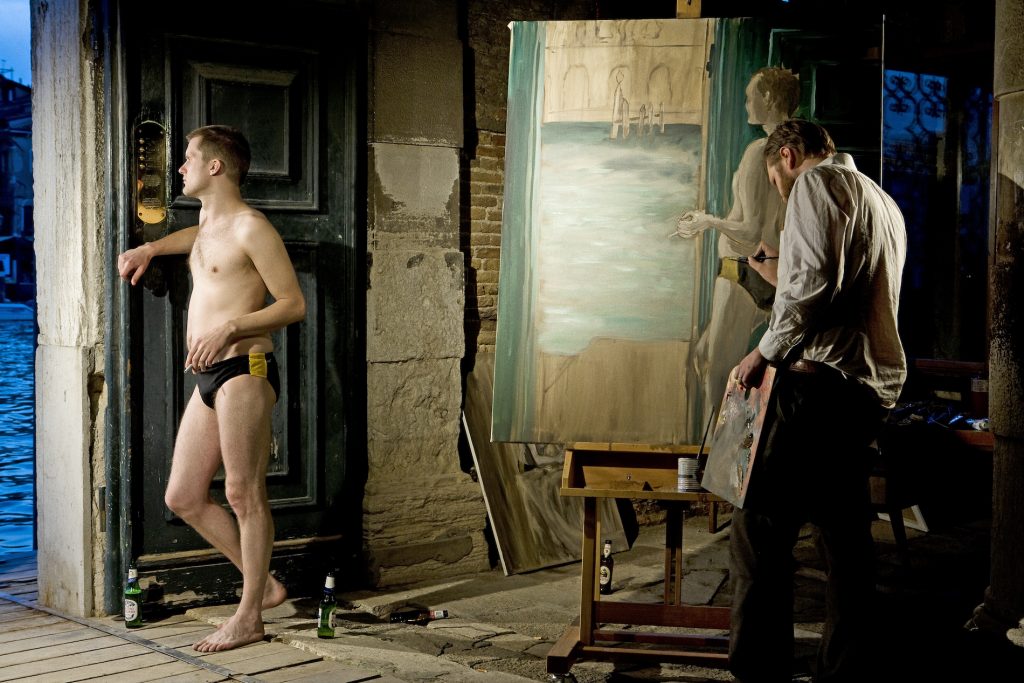

Ragnar Kjartansson work is boring. Of course, it’s not boring boring. I’m just writing that to shake you from your over-stimulated malaise. No, the Icelandic artist’s performance and video work has long mined the experience of monotony. Repetition and a stretched duration are Kjartansson’s hallmarks. An early work, God (2007), for example, features Kjartansson as a crooner fronting an orchestra who play along with his single-line refrain which repeats ad nauseum “Sorrow conquers happiness”. Seven years later the artist persuaded the rock band The National to likewise perform their song Sorrow over and over again for six hours one day in 2014. A Lot of Sorrow takes the audience on an epic journey of fluctuating emotion: the melancholy and raw emotion of the original song is soon replaced with mirth at the absurdity of the situation; hours in the tedium and a sense of cynicism percolate as the band goes through the motions. The now-familiar lyrics begin to gnaw away however until one emerges from the work psychologically wrung out. Kjartansson himself has spoken of how performing in his own work can take its toll: representing Iceland in the Venice Biennale in 2009, the artist was left drained after spending every day of the exhibition’s six-month run painting the same sitter’s portrait over and over again.

The discombobulation the viewer feels on experiencing Kjartansson’s epic work (and, presumably that which the artist feels himself) is perhaps aligned with Kracauer’s idea of “extraordinary, radical boredom”. It provides a space of concentrated looking in which all other stimuli are closed off. In a sense, a return to a classical notion of artistic connoisseurship, yet (to paraphrase Leo Tolstoy’s description of Victorian art critic John Ruskin), Kjartansson is a man who “thinks with their heart”: within its knowing play to our emotions his work contains questions of identity, authenticity and the elasticity of time.

Nowhere is this more noticeable in Figures in the Landscape, the artist’s new commission for the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences at the University of Copenhagen (and also recently shown at the artist’s gallery, i8, in Reykjavik). Consisting of seven single-channel videos, every twenty-four hours in length, the week-long work features silent young medics, dressed in white coats, interacting, meandering, and resting across a variety of stage set environments. The ‘action’, so-to-speak is reduced to events such as a meeting held in a woodland scene, two doctors hug in a snowstorm, another wanders a desert hands held behind his back. For great swathes of the week’s worth of footage, however, the painted scenery is left devoid of actors. To watch the work is to view a clock slowly ticking away: leaving one in an almost transcendental place of meditation.

This article is republished from TLmag 31 Extended: Islands of Creation.

Cover image: God, 2007, single-channel video installation, Commissioned by TBA 21, Vienna and The Living Art Museum, Reykjavik, Courtesy of the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York & i8 Gallery, Reykjavik.