Aric Chen – Curating Hong Kong

Aric Chen spoke to TLmag about his curatorial philosophy, professional trajectory and role at the new M+ Museum in West Kowloon Cultural District, Hong Kong.

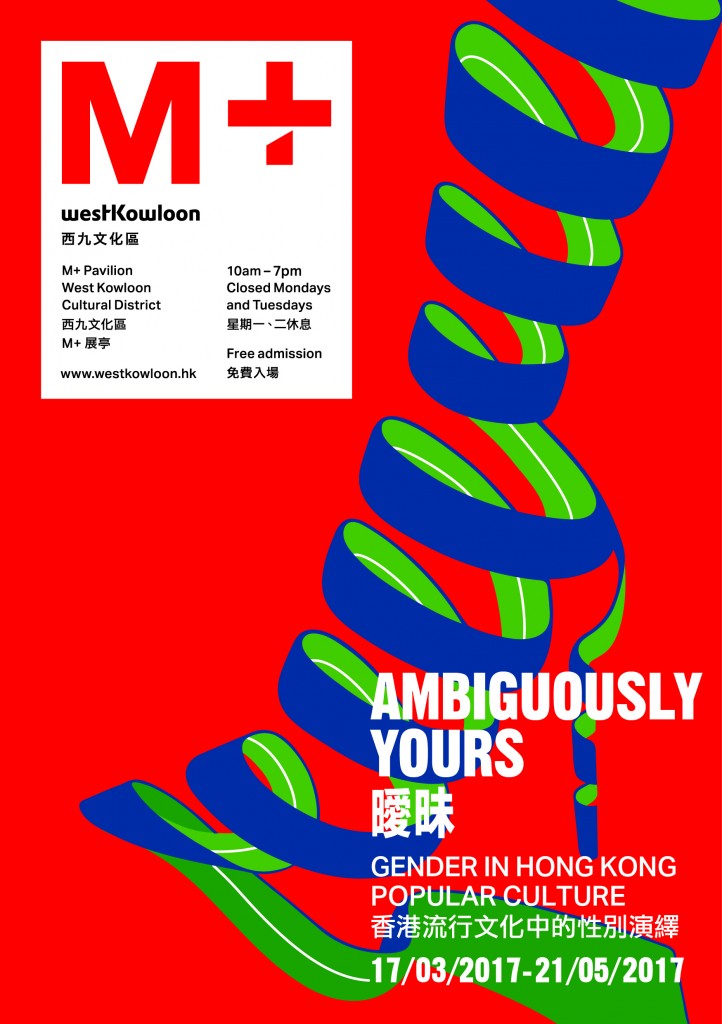

With an education in practical architecture, scientific anthropology and the connoisseurship of the decorative arts, Aric Chen has developed a dynamic curatorial approach that values different perspectives. Channelling his own culturally diverse heritage, the Chinese-American curator sees this complexity as central to his job organising architecture and design at Hong Kong’s M+ Museum, for which he has developed a series of temporary and traveling exhibitions since accepting the position in 2012. The permanent Herzog de Meuron-designed building with its expansive exhibition space is set to open within the new West Kowloon Cultural District in late 2019. For him, the new institution will be a fresh and formidable voice in a predominately American and European museological discourse. Chen has the exceptional yet challenging responsibility of building a 20th-century collection from scratch and establishing new precedents for how architecture, design, and material culture are defined within the local, regional and global context. Chen spoke to TLmag about his curatorial philosophy, professional trajectory and role at the new museum.

TLmag: How does your background in both vocational and theoretical fields influence how you address issues in contemporary design?

Aric Chen: I’ve never thought of these domains as mutually exclusive, but rather parts of a bigger picture. My love of architecture and interest in anthropology, which I studied at the University of California Berkeley, began to inform each other; they were then supplemented by the study of object at the Cooper Hewitt Parsons History of Decorative Arts programme. I’ve always resisted the idea that topics should be looked at using a single method; instead, I believe in the dynamism of multi-angled perspectives. I’m just as happy looking at design through the lens of global capital flows as I am in exploring the aesthetic bewilderment of a ceramic vase.

TLmag: Looking back at your professional path, describe your transition from working as a journalist to becoming a curator. How are both disciplines similar and dissimilar?

A.C.: I ended up writing by accident. From there, I was eventually asked to mount different exhibition projects and slowly transitioned into curation. My first gig was to co-curated – with Laetitia Wolff – the U.S. represent at the 2004 Biennale Internationale Design Saint-Etienne. If you look at architecture and design curators working today, many of us started out in writing. It makes sense if you realise that the same skills are necessary in both domains. Essentially, your job is to be curious and compelling, to see as much as you can, to make considered choices and then to communicate what you’ve interpreted to a larger audience.

TLmag: What project first brought you to China?

A.C.: As a journalist, I was invited by Pearl Lam for the opening of her new Shanghai design gallery, Contrast. Soon after, New York-based conceptual designer Tobias Wong and I were asked to be co-creative directors for a new iteration of 100% Design Fair in Shanghai (now called Design Shanghai). This all coincided with a personal look back at my own cultural heritage. On a whim, I decided to move to Beijing. Soon after, I became the creative director of Beijing Design Week.

TLmag: Why did you transition from directing a festival to curating at a museum?

A.C.: Design fairs and festivals tend to focus on promotion, something I was comfortable with back then. As design was—and still is—a relatively young field, these types of events are important platforms to incubate new artists and ideas, fostering new awareness through a network of designers, schools, buyers, critics, and more. What drew me back to working in a museum like M+ was the need to fill a discursive and historical void in Chinese design culture.

TLmag: How does your own design and curatorial ethos match M+’s mandate and geographic specificity?

A.C.: The M+ project has been in the works for over 20 years now. At some point, there was talk of establishing a new branch of the Guggenheim or Pompidou museums. However, the city ultimately decided to take on the ambitious project of establishing its own institution with a focus on visual culture, including design, architecture, fine arts and the moving image. This goal corresponds to the scope of my education and interest in exploring different perspectives. There is validity to the idea of a cultural ecosystem. You need different types of people and organisations that serve different roles. What’s been missing in Hong Kong and Asia as a whole is a larger platform for these fields. By virtue of its sheer size, M+ will fill this void.

TLmag: How will M+ frame the different creative disciplines in exhibitions and programming? How will you curate design and architecture at the museum?

A.C.: It’s very ingrained in us to consider the fluidity between the different disciplines. That being said, you first need to establish boundaries before blurring them. The approach we’re looking to explore consists of cross-fertilising different dialogues without dismissing the different historical trajectories of each discipline. In China and elsewhere in the region, the contemporary concept of design is still new. At M+, architecture and design will be presented on their own terms. Using a conventional chronological format at first, the stories we want to tell will be revealed as moments of surprise.

TLmag: How are you building the architecture and design collection?

A.C.: We’re collecting based on ideas rather than typologies. We’re equally happy to show a masterpiece by an established artist as we are a cheap plastic phone produced in Shenzhen. The restrictions other institutions and curators work with when collecting are often based on precedent, which we’re not dealing with. That’s the beauty of entering a project on the ground floor. The responsibility of establishing something entirely new is to create as many precedents as possible so that down the line, our successors will not have those excuses.