Bas Smets on Culture and Landscape

Belgian landscape artist Bas Smets guides TLmag through the multifaceted lands he researches before inventing or co-creating his landscapes.

The prolific Brussels-based landscape architect – curator of the upcoming Agora Bordeaux Biennale from Septmber 14 to 24 – Bas Smets has collaborated with major architecture practices such as Frank Gehry and Office Kersten Geers David Van Severen. Smets guides us through the multifaceted lands he researches before inventing or co-creating his landscapes. Examples of such projects include the Tour & Taxis park, located at a post-industrial site, Parreno’s black landscapes, the newly inaugurated Estonian National Museum’s park, the public plazas that have transformed the pearling pathway in Bahrain, and the upcoming Parc des Ateliers in Arles, which will be home to the LUMA Foundation in 2018.

TLmag: Last year you launched the Brussels Urban Landscape Biennale. How is your involvement in this ambitious, new, local programme?

Bas Smets: When we were asked to design an exhibition for the Brussels Urban Landscape Biennale, the first question that came to my mind was: An exhibition about what exactly?

Since this was supposed to be the launch of a new biennale about landscapes, it seemed appropriate to speak about the concept of landscape itself, its origins and its development. Rather than showing best practice projects, international references or our own projects, we decided to collaborate with curators from different artistic disciplines. That allowed us to explore the notion of landscape through painting, cartography, photography, cinema and lastly, landscape architecture. These thirty works of art depicted landscape as a mental construct that helps us to understand the reality around us. Landscape architecture was a later development. It can be regarded as a continuation of these different art forms’ evolving depiction of landscape, thus anchoring it in the long and glorious tradition of landscape representations.

TLmag: In The Invention of Landscape, the exhibition that you curated at BOZAR, you chose nature and culture as two major themes. Your references were closely linked to painting, cartography, engraving, photography and filmmaking. They act as a metaphor, a “window open to the world.” How have the fine arts, in particular Flemish painting from the 16th, 17th and 18th century, played a central role in the formation of contemporary landscapes? What does this mean to you? Do you see it as not just a mental process, but also a deeply physical process? How is that concept expressed through today’s new media?

B.S.: I don’t think in terms of nature and culture, but rather in terms of land and landscape. I base my thinking on Alain Roger’s Court traité du paysage. I have had the chance to have an on-going conversation with him over these last few years and he has had a great influence on my practice. Roger defines the land as the existing condition of physical reality and the landscape as the perception of this reality. The land can only become landscape through a cultural process. The exhibition opensed with the origins of the notion of landscape, showing how it came about as an independent genre with the appearance of windows in 16th century painting in the Low Countries. Then we showed the evolution of early cartography from a mixed genre towards a precise way of measuring the land. In the section on photography, the landscape became a scientific object and we documented its slow transformation over time. In the section on filmmaking, we revealed how the same kind of landscape can be framed in a very different way in order to serve the narrative. Lastly, regarding landscape architecture, we unveiled a new vision for the urban landscape of the Brussels region.

TLmag: The themes of open space and immersive scenography conducted on a human scale run through all the exhibitions you have curated. This also applies to the exhibitions you set up at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Charleroi, at Arc-en-Rêve in Bordeaux and at BOZAR. Does this reflect your highly artistic and visual approach to both your concepts and your projects?

B.S.: Every time we have the opportunity to design an exhibition, we try to make a landscape that is both physical and mental. This time, I wanted the visitor to enter the mind of a landscape. Visitors wander through different layers of a dark room where selected works are illuminated. In the green darkness, the thirty selected works create a specific universe that helps visitors understand the close ties between the different art forms while preserving their complexity. Everything can be viewed all at once yet each individual work commands your attention thanks to the lighting scheme. The idea is that one needs to be moving in order to understand it. Just like landscapes must be experienced, this exhibition must be experienced while moving. In Antwerp, Charleroi and Bordeaux, we wanted to examine methodology in the design of landscape projects. This translated to a certain clarity in the exhibitions. In contrast, the exhibition at BOZAR was more intimate. It created a moment between the visitor and each work of art on exhibit that made it feel like you were entering a three-dimensional Kunstkammer.

TLmag: This brings me to a question about your project with Philippe Parreno and the black landscapes. Could you tell us more about your close collaboration with this internationally acclaimed contemporary artist? How did you feel about your role in this project, which consisted in building a landscape from scratch? Beyond land-themed art, have you worked with concepts such as entropy?

B.S.: Philippe Parreno wanted to make a landscape that could only exist in a movie. NASA had just discovered that life could exist on a dwarf planet lit by two suns, whereas they had only been looking for life on a planet similar to ours, lit by one sun. Philippe wanted to film the landscape of that extra-terrestrial planet. He asked me if I could help him design the set for this landscape. This turned out to be a very exciting, inspiring partnership, which resulted in the short film Continuously Habitable Zones, or CHZ. That is the term used by NASA to describe places where extra-terrestrial life is possible. I started reading NASA literature on the topic and learned that because of accelerated photosynthesis, the landscape on that kind of planet would most likely be very dark green, almost black. We decided to only use black plants. In order to reveal a landscape that is both existing and unseen, we uprooted trees, burnt the surface of the earth, dug and scratched. The landscape then became a movie set and was filmed using day for night techniques. Cinematographer Darius Khondji explored it just like an astronaut would explore a new planet. This adventure gave me some essential insight. Whereas we landscape architects make images that we transform into reality, filmmakers create a reality that then produces images. The two approaches create a cycle of reality, transformed into images while transforming reality. It’s an endless cycle, just like the seasons.

TLmag: The city is a juxtaposition of various layers made of both built and green environments that play off of one another. With that in mind, how do you see Brussels from an historical and a contemporary point of view?

B.S.: Brussels lost its main river, the Senne, when it was redirected underneath the city centre. Unlike cities such as Paris, London and Amsterdam, the main element that structures Brussels is not visible. Instead of deploring this loss, we have been crafting a new image for Brussels. Our studies showed that the Senne valley has been transformed into a valley of parallel infrastructures over time. A canal, several railways and many roads have been constructed parallel to the valley’s contour lines. Even if the river runs underground, it has had a very strong impact above ground. Although the main river runs underground, its tributaries are still visible. The parks and green spaces of Brussels feel fragmented and dispersed. Yet when you superpose the tributary river system on Brussels, a new structure reveals itself. Almost all of the city’s parks and green spaces are connected to these secondary waterways. We produced new images that show how the eight catchment basins of the Senne could become the blueprint for an inventive system of parks. We can replace the image of the main river flowing through the valley unseen with the image of the tributary valleys. Whereas it may seem like common sense to try to re-establish the Senne River as the backbone of the city, this new tributary image suggests a radically different approach. Together, the eight tributary valleys could become the defining image of Brussels. In recent years, flooding has been a real problem in our capital. This new park system would not only create a number of continuous green spaces but it would also solve the flooding problem by expanding the capacity of each catchment basin.

TLmag: You have worked on very large regional projects such as Tour & Taxis. How did you get involved and how have you contributed to regional renewal efforts? What is your plan for bringing nature back at this post-industrial site?

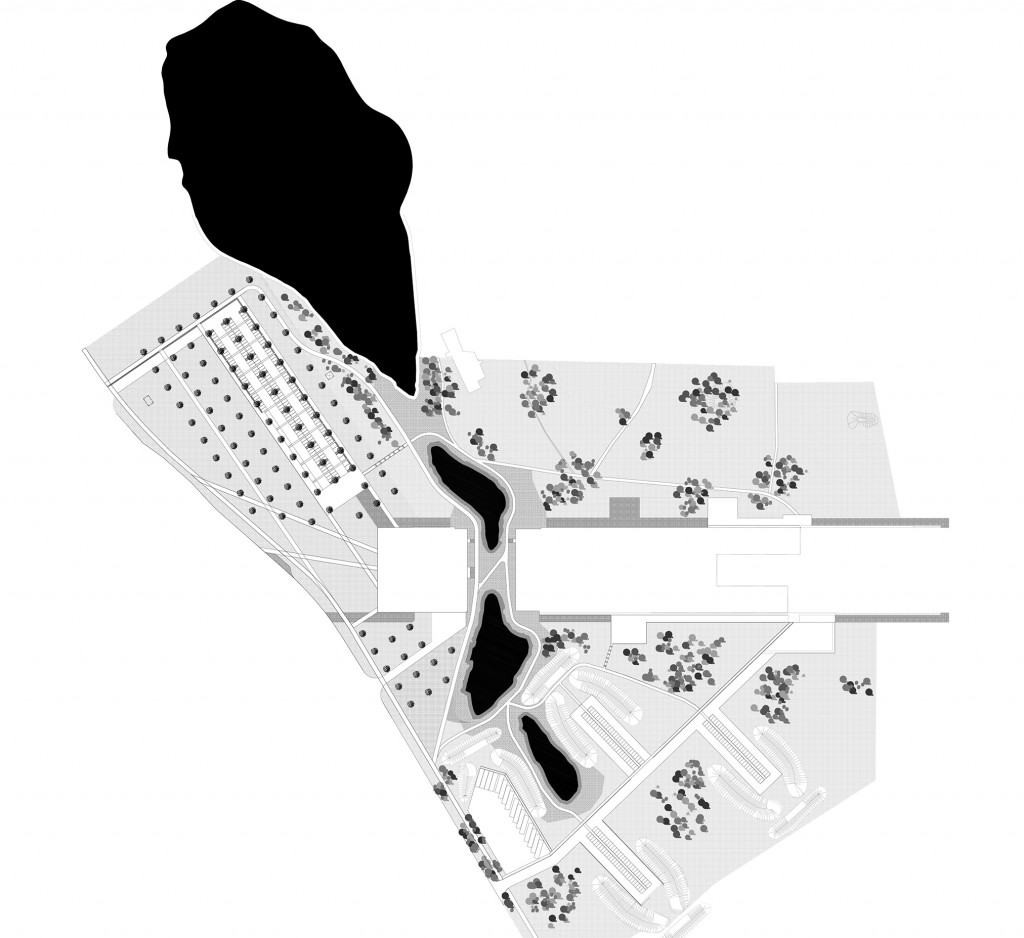

B.S.: The site of Tour & Taxis used to be a major transit hub for goods passing through Brussels. There were customs buildings, warehouses and a large rail yard. These activities started to decline in the late 1960s. Today, much of this large terrain, which measures 45 hectares, lies vacant. The goal is to convert the site into a new neighbourhood in the centre of Brussels. There will be a new park at its core totalling more than 10 hectares. The site is situated on the west side of the Senne valley and has the potential to become part of the tributary system. However, the existing terrain was flattened and a layer of ballast was added as a foundation for the railroad tracks, thereby rendering most of the surface sterile and impermeable. First, we scraped off the upper layer that had been added and filtered it into its primary components: rough gravel, fine sand and topsoil. We subsequently reshaped the site using these materials without bringing in any additional soil from external sources. The newly created slopes guide the flow of rainwater into two central areas. There, the water infiltrates the ground and flows into sub-surface retention basins that were created using the filtered rough gravel. Then we planted a mix of over 3,000 pioneer trees and 300 long-lived trees. The pioneers ensure that there is an immediate vegetal presence on the site. Planted in a dense grid formation, they will act as a visual screen. They will block off the view of the surrounding building construction, which will begin after the park has been completed.

Additionally, they will improve the soil quality, paving the way for the long-lived trees, which will be spaced further apart. Once the surrounding buildings have been completed, the pioneers will be cleared away in order to create a sequence of views and passages. The repurposing of the site’s existing materials and the phased vegetation plantings make this project a truly evolving park.

TLmag: How would you define the parameters and the design of the park you completed for the new Estonian National Museum in Tartu?

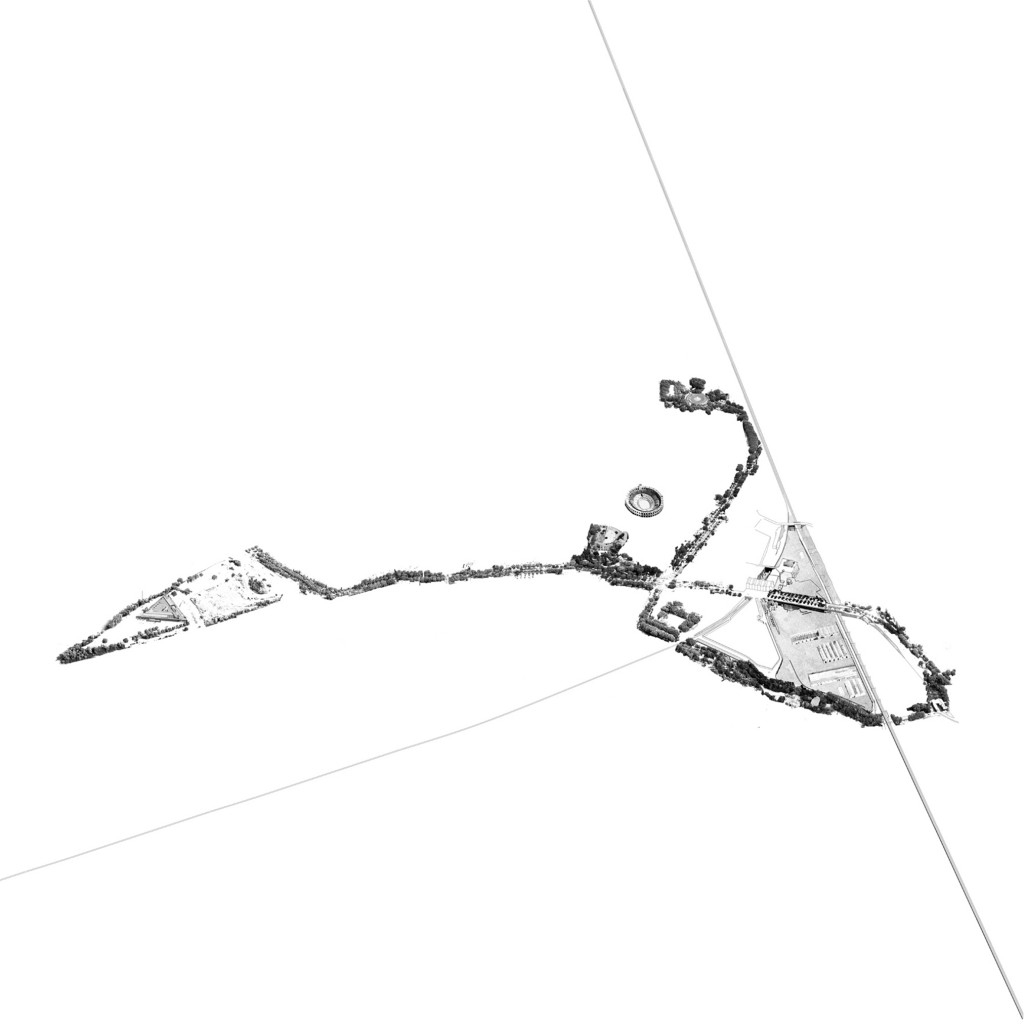

B.S.: The Estonian National Museum and the museum park just opened on 1 October. The site is a former Russian army base, built during World War II. It served as the main Russian airbase for Scandinavia. Tupolevs would constantly be landing on the different airstrips. When the Russian army left, the site was deserted and pioneer vegetation emerged in between the landing strips. This young, fragile landscape, mainly comprised of birches, ashes and meadow flowers, covered up the traces of the Russian presence at a time when the Estonians were gaining their independence. This spontaneous landscape is Estonian by definition. It is the vegetation that nature created in the absence of human intervention. Our project aims to reveal this pioneer landscape, rather than replace it with a new one. The project is based on two distinct smaller projects. First, the excavation of two new lakes brings the existing lakes into one single hydraulic system. This new lake system is reminiscent of the great Estonian landscapes. Second, an orthogonal tree grid contrasts with the existing spontaneous trees. This wide grid filters the views and invites visitors to discover the preserved landscape unravelling in the background. All of the exterior functions of the museum, such as the drop-off area, the car park and the bus stop, are organised underneath this grid, marking the entrance to the museum.

TLmag: Regarding the Parc des Ateliers in Arles, which will be home to the LUMA Foundation starting in 2018, how has your experience been working closely with the Frank Gehry architecture practice?

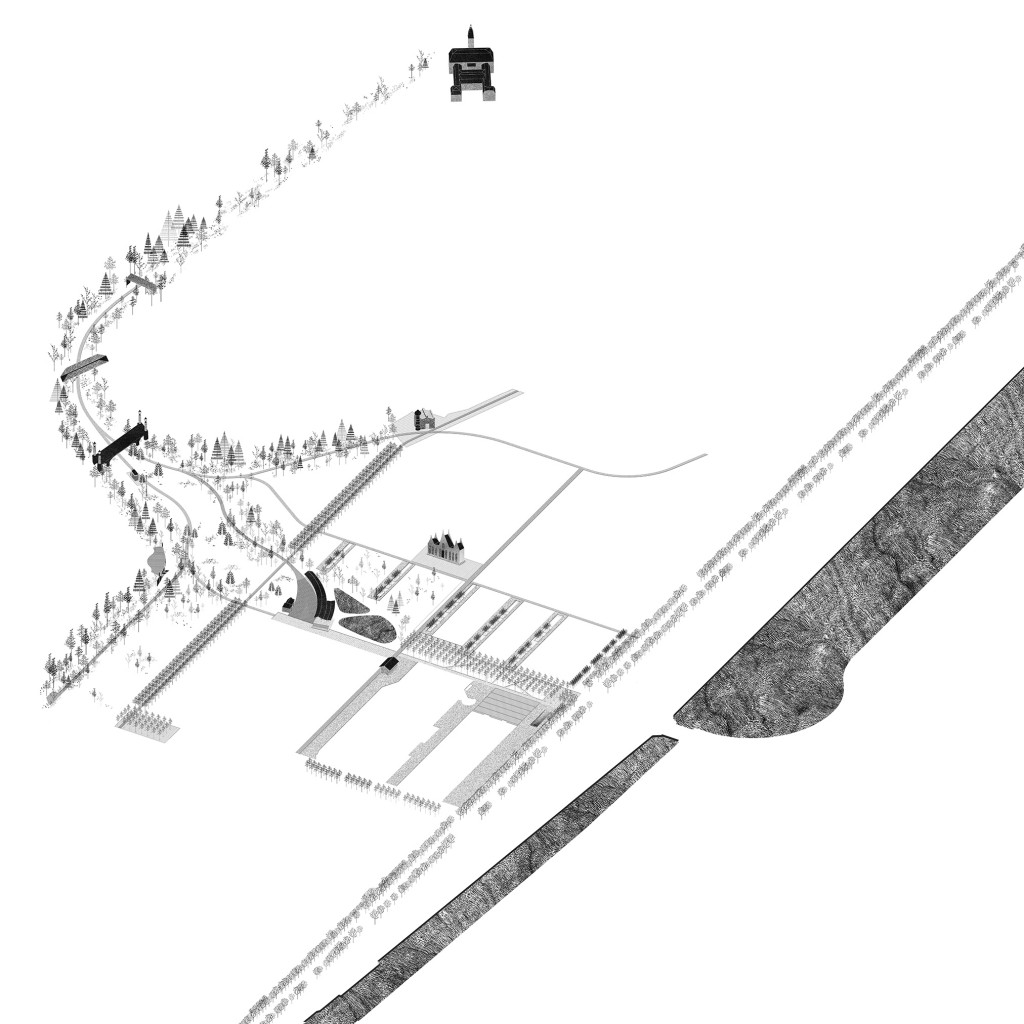

B.S.: The site of the Parc des Ateliers is exceptional, not only in terms of its history but also its location. The surrounding landscape is characterised by three very different geomorphic features. The first is the Camargue, the estuarine flood plain of the Rhône. The second is La Crau, a stony plateau devoid of trees. The third is Les Alpilles, a small chain of rugged limestone mountains. The Parc des Ateliers lies right in the middle of these three landscapes. How will they influence the site and its future landscape design? The Parc des Ateliers is located in between historic, small-scale, city centre squares and contemporary, large-scale open spaces at the outskirts of the city. All of these public spaces are connected by a boulevard that forms a loop around the Parc des Ateliers. This public loop is recognisable thanks to its continuous lines of trees. The Parc des Ateliers stands on a plateau, excavated from the bedrock. This artificial platform provides the opportunity to create a large public park within the city of Arles. It will be different from the existing outdoor spaces both in terms of its scale and its atmosphere. Inserted into the urban fabric like a wedge, the Parc des Ateliers will connect with the public, tree-lined loop at two intersections. A site that has been closed for decades will be reopened at these intersections with the tree-lined loop connecting the Parc des Ateliers to the city centre.

Five hundred trees will transform the former concrete platform of the Parc des Ateliers into a green oasis. Each tree species is specific to the Mediterranean landscape and has been carefully selected from the best nurseries of Europe. Together, they will create a new environment at the Parc des Ateliers. The trees will throw shade on the grass below and create places to sit. Thanks to the leaves’ evaporation and transpiration processes, the trees will bring down the temperature in the summer. Their branches will provide protection from the mistral winds in the winter and their shifting colours will announce the change of seasons in between the renovated exhibition buildings.

The choice of vegetation will create a sequence of landscapes throughout this former rail yard that will be reminiscent of the beautiful landscapes that surround Arles. From the exceptional pine trees around the Frank Gehry building to the weeping willows edging the lake and the cedar trees on the park’s mounds, this new, rich environment will attract both inhabitants and visitors.

TLmag: You are also co-designing public squares in Bahrain together with the Brussels-based architects Office Kersten Geers David Van Severen. Could you tell me about the innovative ways that you and Office have shaped these new public spaces? They were not really part of the former pearling industry in the Middle East but you found a new way for them to exist and function.

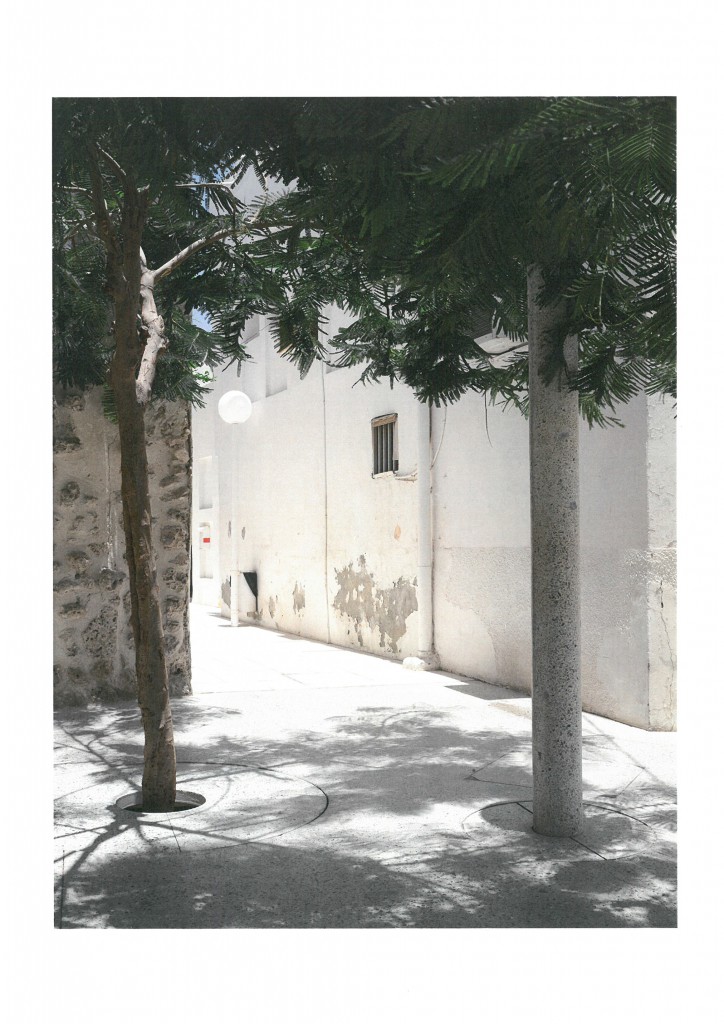

B.S.: The Muharraq peninsula used to be an amazing place. Its warehouses were attached to the land but maintained a connection with the Gulf. In older photographs, the city looks like Venice. Unfortunately, a ring road was built on a landfill around the original peninsula. The city lost its connection with the water along with its views of the vast watery landscape. When UNESCO listed 17 pearling buildings as World Heritage sites, the issue of pathways emerged. Together with Office, we won the competition for this pearling pathway, or pearl path, as we dubbed it. Instead of creating a visible path to link the 17 buildings, we focussed on the opportunities along this path. We discovered that many buildings along the path had been destroyed. Instead of rebuilding them, we suggested replacing them with 23 public plazas. This creates an internal landscape made up of fragmented squares, which replace the external gulf landscape that was once there. Every square was designed as an outdoor room. The volume of the previous building is then replaced by an equivalent volume of trees. These trees create a constant canopy that blocks out the sun. We are experimenting with solar cooling, using sunlight to cool the flooring of the plaza. This creates a microclimate between the cool concrete flooring and the tree canopy. Just before I began this project, I went walking around Corsica. I admired the way the paths there were marked with simple stacks of stones set on top of another. I suggested that we use a similarly simple language, taking elements that were already part of the public space instead of marking the path between these plazas. We decided to introduce specific urban furniture. The light posts, dustbins and benches help visitors find their way from one plaza to another.

Discover more projects at www.bassmets.be