BassamFellows: Authenticating a Lifestyle

Establishing a firm position on the international scene, TLmag 23-featured BassamFellows have reaffirmed the steadfast value of American design since first founding their practice in 2003. Transcending the architectural savior-faire of Craig Bassam with the creative branding expertise of Scott Fellows, the interdisciplinary duo continues to play a major role in the craft revival. Consulting commissions have taken them from Swiss shoe brand Bally to Herman Miller, with interior projects the world over. Blending modernism and honest artisanal production to create a holistic boutique label – combining new leather-based fashion and noble material accessory lines with an already rich gamut of minimalist furniture – all centred around their own Philip Johnson-designed house. TLmag caught-up with Scott Fellows at Atelier Courbet in New York, where the Connecticut-based design house mounted a special showcase this November and December. Such a context was the perfect backdrop – far from the hustle of major fairs like Milan’s Salone del Mobile, where BassamFellows frequently exhibits – to take an in-depth look at a philosophy, process, influence, culture and future perspective that covers all the bases.

TLmag: How was your founding Craftsman Modern ethos a reaction and revolution in 2003?

Scott Fellows: Change was happening for us personally and in the marketplace. I was just coming off of a three year project turning around Swiss shoe brand Bally and before that work with Ferragamo as it grew into a multinational. Craig was working as an architect and interior designer. For both of us, it was a question of if we wanted to cement our careers in these respective paths or to create a brand with our own DNA; a challenge compared to working with historical brands that have ingrained identities. However, It was a ‘now or never’ moment. The luxury industry was changing. When I first started working in this sector, companies were focused on creating beautiful objects with traditional materials and craftsmanship that ensured longevity. By the early 2000s, it became more about marketing and less about quality products. They were looking beyond production in France or Italy and started to consider Spain and Asia as viable alternatives in order to reduce costs. These fashion brands were also expanding into new applications, including home collections. We saw an opportunity to focus on the home sector in an authentic way by merging our two backgrounds: furniture designed by an architect using the best craft and materials normally associated with luxury goods.

TLmag: What was important for both of you in establishing a new brand?

S.F.: In his own practice, Craig always used classics. We both loved the craftsmanship, quality of material and timelessness found in designs by modernists like Mies van der Rohe or Marcel Breuer. In 2003, the market was dominated by the latest technological advancements coming out of Italy: moulded foam, inject-moulded plastic, CNC-cutting or computer-based designs all maintained a highly industrial approach. It was clear that this trend was coming to a logical end. For us, much of this output didn’t sit well with the spaces we were developing. We saw an opportunity to try something entirely different: furniture that was both contemporary and that followed in the same lineage as the classics. Taking my background in luxury, Craig’s modernist approach and the home as our core, we decided to create an identity from scratch. It was the right time to do so.

Presenting our first collection at the 2003 Salone del Mobile, we found ourself in a sea of Philippe Starck and Starck-inspired designs. Our stand was an island focused on craft and traditional, natural materials – something that, at the time, was still seen as rustic, while others saw it as highly expensive studio furniture. Art design galleries and events like Design Miami were just starting to appear. Suffice it to say, craft wasn’t viewed as chic or sophisticated. Our presence in Milan was still quite jarring for most people but the New York Times featured us as part of their roundup which proved that key people, but not everyone understood what were doing: transcending artisanal and industrial production. Of course our young brand couldn’t compete with big Italian powerhouses. The sector we were entering offered an entirely new price point. Contemporary furniture is often viewed as being very expensive but is nothing compared to more artful limited edition works. We decided to place ourself between the two extremes. At first, people didn’t understand or think it could work but we proved them wrong over the past 12-years.

TLmag: Why did you create a holistic identity, addressing different applications?

S.F.: With so much choice out there, cutting through the noise is a real challenge. It requires a lot of resources to do so, which is why major luxury brands have bought up smaller producers and consolidated. I’ve always been in favour of lifestyle-oriented companies and for us, it made sense to find our niche in such an approach: building our own market with a clear vision. The word lifestyle, like quality or luxury for that matter, takes on a negative connotation associated with marketing hype. There’s nothing true or authentic about that statement. It was the total opposite for us, as our designs actually reflected our own lifestyle; a means of articulating a singular vision.

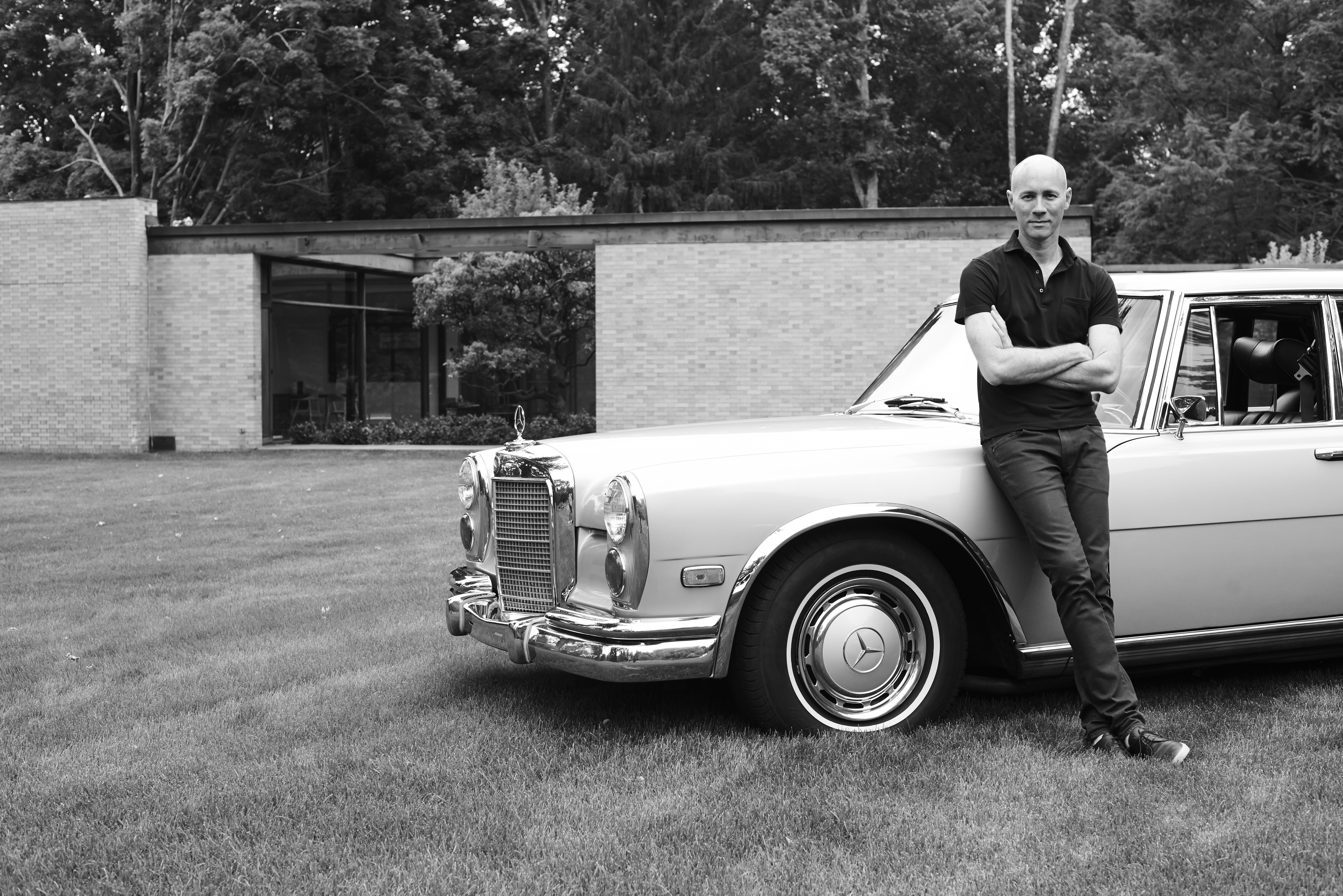

Today, we can take a beautiful chair or table and put it in the context of our Philip Johnson-design house and describe our direction; showing that these pieces can work with other fashion or accessory products. It’s often a conscious choice to do so: giving our clients and potential customers a broader view in situ.

In the early days, we struggled in communicating the scope of our varied expertise: architecture, interiors, furniture, fashion, branding and consultancy. We had a hard time describing what it was we did and were afraid of being seen as unfocused but we soon realised that was our strength. The new way of working is very much the Hollywood model: larger productions that bring in different levels of skilled professionals together for short periods before they disperse into other projects. That’s very much how we work too. Craig and I get many calls from clients who want us to develop a project and by doing so, get a taste of our vision. We enter and leave these commissions but sometimes return again and again, like with Herman Miller. Each endeavour informs the next as part of the same vision.

TLmag: How did the craft revival of the last decade come about?

S.F.: In the United States, the seeds of this movement came from the food industry. Starting in the fringes of Los Angeles and Napa foodie scenes, people started to backlash against large industrial food production, where they didn’t know where the food they were eating came from. The farm to table concept started to show up everywhere and not in the least, design. The ideas of locally sourced material and production, as well as environmental responsibility, became important, especially among millennials. For us this became crucial in the woods we sourced and the skilled craftsman we employed. While living in Switzerland, we worked with a great cabinet maker but as we moved back to the United States, we needed to find something comparable, which wasn’t easy. We now produce in Pennsylvania.

TLmag: Have you witnessed a change in how young practitioners start out?

S.F.: You do see many new studios and brands popping up. Everyone seems to be working with the same set of tools; starting from a craft foundation and working with materials like brass and wood. With these materials plentiful in the United States, you can still find craftspeople. When talking to former colleagues in the luxury industry, many think that if the next generation keeps this movement going, the United States will be able to rival craft production in Europe. It needs to be more than just a hipster trend. There’s great momentum. Even some of our Italian producers admit that they would pick up everything and start afresh in the United States. In Europe, the recession killed many of the smaller ateliers focused on specific parts of production with the rest having been picked up by bigger groups. For us it was hard to find the best manufacturers, who hadn’t been snatched up but now, we produce our shoes with a fourth generation family company in Italy. We aren’t solely focused on producing in the United States. Early next year, we will again produce some of our furniture in Italy as demand for our designs grow in Europe.

TLmag: Describe your European following.

S.F.: We opened our Milan gallery two years ago with great success but we are also very pleased with the results in Paris and Belgium, where Craig and I have worked with great architects and interior designers. We’ve worked with people like Vincent Van Duysen – whom we brought in to design some products at Herman Miller. Both Craig and I love the Belgian style: the perfect balance of Minimalism and high craft. We develop many custom pieces for that market such as our Circular Table that had to be enlarged from a 6 seater 52-inch model to a 2.4-meter 12 seater iteration. In other parts of Europe, Spain is also a growing market. We just collaborated with Herzog de Meuron on a custome pieces for a project there. However vastly different by region, the European market seems more intimate. Our Milan-based gallerist has great relationships with firms throughout the continent.

TLmag: How would you define a Swiss design identity?

S.F.: Both Craig and I loved living in Switzerland, on and off, for six years. What we love about this context and integrate into our DNA is a connection to nature. When looking around, you’re inundated with extreme elements in the best way possible. This appreciation comes through the woods we use. We really let these materials exude their own beauty without masking them with lacquers or other coatings. In Switzerland, it’s also a question of precision that can be seen in everything from small objects to the built environment. It’s hard to find the same attention to detail and quality in the United States. Such conditions require both makers and clients have that same culture. What is rare in the United States, is ubiquitous in Switzerland.

Our adherence to minimalism has nothing to do with the sometimes watered-down strains of this movement found in the United States, where it’s often misunderstood as devoid of detail. For us, it’s the complete opposite. Minimalism is about refinement and concentration, stripping the unnecessary away to find the essential.