Becoming Fair(er): Can this be the future of smartphones?

Fairphone is an Amsterdam-based social enterprise and smartphone manufacturer that tries to flip the industry that is hugely (environmentally) damaging.

“Smartphones have never been regulated at EU level” explains Chloé Mikolajczak, a campaigner at the activist organisation Right to Repair. This lack of regulation has led to the rise of an industry that is hugely exploitative, abusive, and environmentally damaging. Despite a plethora of studies, articles and documentaries that highlight the horridness of smartphone production, the industry giants such as Apple, Samsung, and Google, continue to operate unchecked and unrestricted. Why?

“Smartphones are very political,” explains Mikolajczak, “for years, policymakers have been avoiding the topic [of smartphone regulation] because they don’t want to take on the manufacturers and the industry lobbies that are very very powerful.” However, there is one group prepared to defy the wilful blindness surrounding the unethical production of smartphones: Fairphone.

Fairphone is an Amsterdam-based social enterprise and smartphone manufacturer that has been designing and selling smartphones “that care for people and the planet” since 2013. In choosing the name “Fairphone”, the company positions itself in direct opposition to other phone manufacturers, which, by default, must be unfair phones.

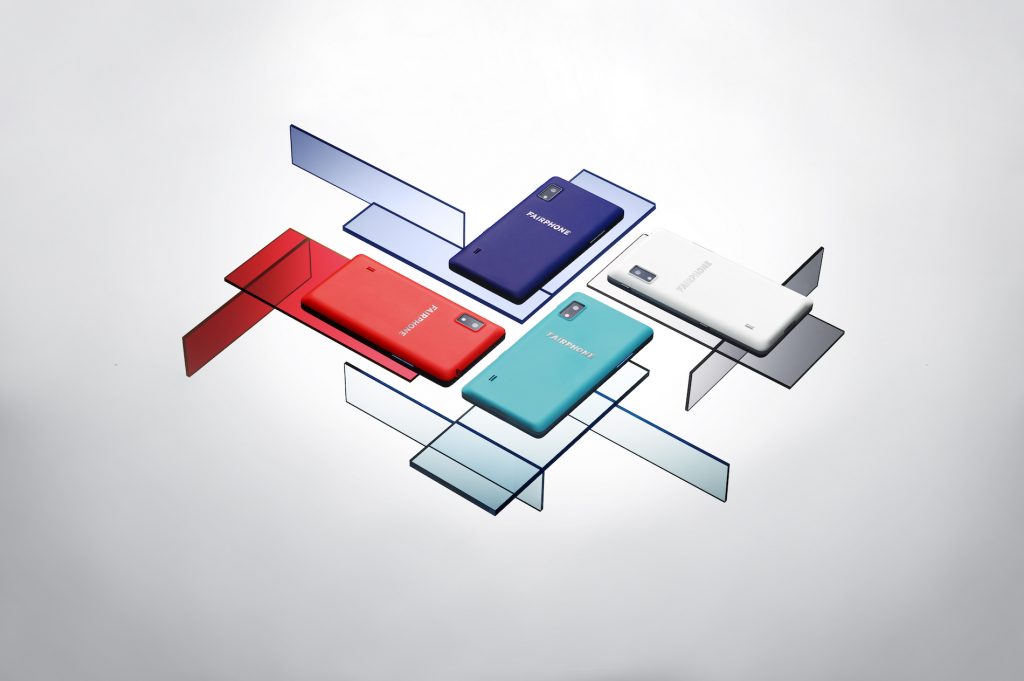

Browsing Fairphone’s website, you will learn that the enterprise has dedicated years to developing supply chains that source the minerals in your phone (for example, tungsten which makes your phone vibrate) from conflict-free mines, ensuring warlords are not profiting from smartphone productions or imposing slave-like conditions on their workers. Furthermore, at the manufacturing stage, Fairphone is “improving worker representation, health and safety” and aims “to bridge the gap between minimum and living wages in the factory.” Finally, at the consumer stage, the devices’ “modular architecture” allows for repairability by consumers. In theory, this enables the longevity of the product by facilitating repair rather than replacement making it financially and environmentally “fair”.

However, when you delve a little deeper into their press releases and articles about Fairphone, it becomes clear that there are some paradoxes and contradictions at play that undermine their rhetoric of fairness. While Fairphone is significantly fairer than its competitors such as Apple, Google, and Samsung, it is not 100% fair and should, perhaps more accurately, be called the Fair(er) phone. One example of unfairness at play is Fairphone’s “decision to follow the entrenched supply chain to China where labour conditions are ‘unfair’ by any standards acceptable to the Global North”. Furthermore, for economic reasons, Fairphone ceased making spare parts and upgrades to the Fairphone 1 in 2017. Therefore customers who bought this phone in 2013 can no longer repair and fix it despite a promise for longevity on purchase.

Despite the shortcomings in production and distribution, Fairphone has made a significant mark on the discourse and awareness around smartphone production and has gone a long way to achieving its mission of “motivating the entire industry to act more responsibly,”

Fairphone, then, is not simply a phone but an agent for change, an illustration, or a proof-of-concept that other ways of being and producing are possible. By problematizing the dominant model of smartphone production and illustrating an alternative, fairer approach, Fairphone tangibly demonstrates that the current model of production is a choice. Being unethical is a choice. Designing for obsolescence is a choice. Limiting consumer’s ability to repair is a choice. These choices, made by industry giants, force people into buying new phones more and more frequently – indeed in the EU alone a shiny, sleek new phone is sold every 6.7 seconds. And, these choices continue to be made because being more ethical and creating repairable products are synonymous with profit-loss. But what would happen if these choices were curtailed?

In October 2019, the EU Commission announced the Circular Economy Action Plan (CAEP) which aims to make legislation that would introduce and enforce standards of repairability necessary on all electronic products, including smartphones. “This is historic, it’s huge,” explains Mikolajczak. However, she also stresses that before celebrating we need to ensure this provision “becomes a reality. It must not be watered down by industry during the process of legislating.” In warning, Mikolajczak cites the example of the universal smartphone charger. For over a decade, the EU Commission has been pushing for all smartphones from all companies to share a common charger to reduce e-waste. Yet, we still find ourselves with different chargers for all our products because Apple has spent billions of dollars on lawyers and lobbying that has ensured this regulation has never come to pass.

While the CEAP does not explicitly address the environmentally damaging and exploitative working conditions of smartphone production these issues would be significantly mitigated through repairability. Every new phone perpetuates the cycles of exploitation and environmental damage, in fact, 80% of the direct climate impact of smartphones occurs at the manufacturing stage due to the energy-intensive processes and rare metals involved. Likewise, much of the human rights exploitation and toxicity to workers occurs at this stage. Simply put, the more a phone can be repaired and updated, the fewer new phones need to enter the marketplace and therefore less damage is done to people and the planet in the first place.

What Fairphone’s challenging and sometimes contradictory journey over the past seven years demonstrates is that are no simple solutions to fixing an industry whose rotten roots have been allowed to grow and proliferate unchecked for so many years. It will take multiple stakeholders, multiple years and multiple systematic changes to create a true shift in production standards. It cannot be done by a single company alone, but a single company can make us think about how we measure success. What happens when human life and environmental life are prioritized over profits?

All photos courtesy Fairphone