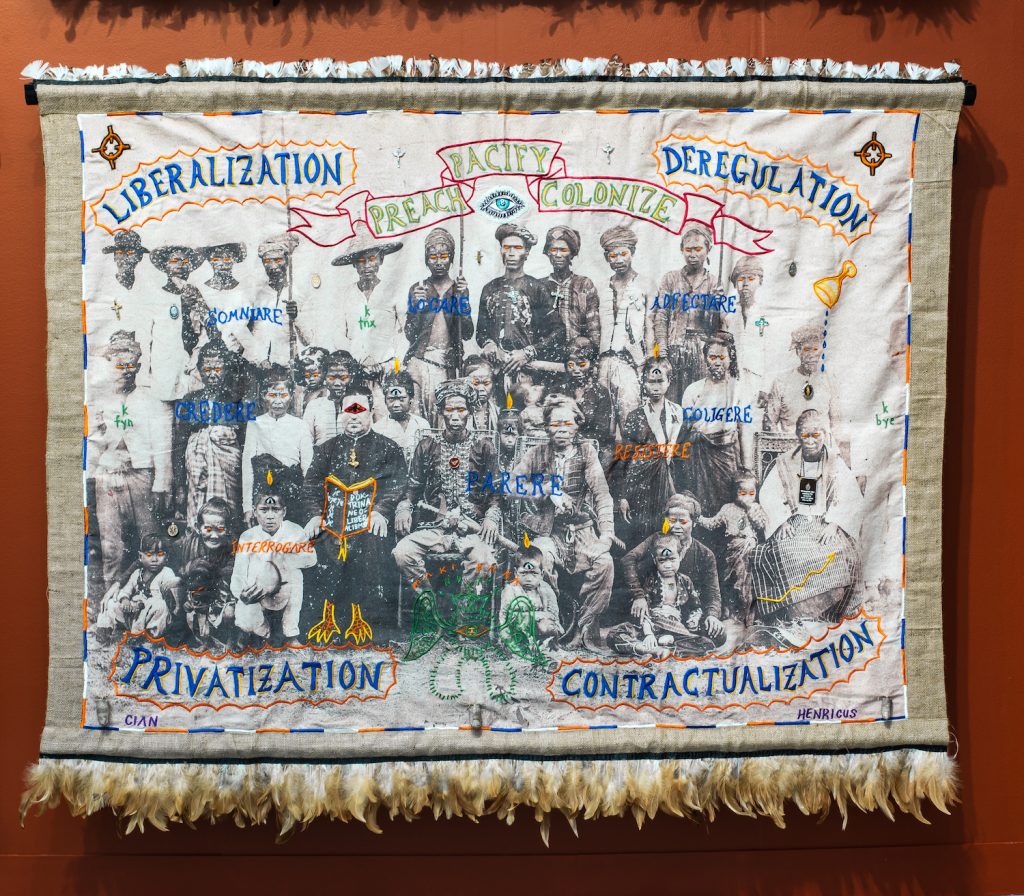

Cian Dayrit – Fabric & Needlework

Equal parts artist and activist, Cian Dayrit sat down with TLmag to explain why his art – usually in the form of embroidered textiles – fights against all forms of oppression across the globe and becomes a place of hope where social justice can survive and thrive.

Words like “Down with US-China imperialism”, “Educate, agitate, organize, mobilize”, “Address the roots of armed struggle”, “Resistance” and “Justice” embroidered in brightly-coloured thread populate Cian Dayrit’s textile artworks. As much social activist as artist, his commentary on the expulsion of indigenous peoples from their land, the exploitation of a nation’s natural resources, the reproduction of feudal land relations and the damage of neoliberalism in his native Philippines is a call to action. He advocates for the inclusion of the narratives of underrepresented populations, playing his part as one small element of a larger collective resistance. In his hands, maps – which have historically been instruments of governance, discipline and control by imperial powers, strengthening the sovereignty of colonialist rulers while side-lining entire regions and populations – are transformed into representations of alternate worlds. Working as a counter-cartographer on hand-embroidered fabrics or over-painted collages of colonial-era maps where cartography becomes an emancipatory exercise, he marks out the extraction of raw materials, land grabbing and dispossession, thereby redrawing the boundaries of “official” history that distribute resources unequally. By disrupting the dividing lines of maps and reconfiguring power, he invites viewers to rethink the ways in which they spatially perceive and interpret the world.

TLmag: You were born in Manila in 1989. Tell me about your parents, your childhood and how you became interested in art.

Cian Dayrit: I come from a middle-class Catholic family in the city. We were relatively comfortable in a relatively uncomfortable society where privilege is a currency. I don’t remember exactly how I came to be an artist. There were several factors, one of which was recognising that art, cultural work in a broader sense, was an opportunity to engage in direct action to learn and address the contradictions of our current social order, which of course I had yet to fully understand. I remember watching some videos of a massacre of farmers protesting in 2004. I was totally destroyed by the idea that such injustice had been happening just outside my comfortable urban bubble.

TLmag: Why have you chosen to focus on notions of power and identity as represented and reproduced in monuments, museums and maps?

CD: Growing up, I was always fascinated by how these objects and places commanded so much power by dictating how civilisation is perceived. I was equally entranced and horrified by how the people who made these things could impose their perspectives onto everyone else. In response to the immediate conditions that I was slowly recognising, I wanted to challenge the perspectives that somehow monopolised the framing of history and heritage.

Activism taught me that by learning from and putting to the fore the narratives of the deliberately silenced marginalised sectors, social justice can be realised. By subverting the language of these institutions, I felt that I was filling in the gaps and democratising the functions of narrative.

TLmag: How has the colonial history of the Philippines informed your work?

CD: The colonial histories of the Philippines and other nations are natural departure points in discussing current struggles. Colonialism never ended; it only evolved into contemporary iterations of oppression and exploitation on several levels.

TLmag: Tell me about your time spent with indigenous peoples, peasants, the urban poor and refugees, and your map-drawing workshops. Why are you interested in defending the marginalised and disenfranchised, particularly populations who have been dispossessed of their ancestral land?

CD: The history of the Philippines is a history of struggle between the ruling classes and the broad masses who are marginalised and systemically oppressed. In this context, one has to take on a side. By remaining neutral, you are naturally siding with the oppressive system.

Peasants, workers, the urban poor and ethno-linguistic minorities all bear the brunt of centuries of abuse. We need to try to understand the structures in which culture, economics and politics function. My practice is activated by solidarity in the struggles of oppressed populations.

TLmag: Is it important that your work tackles socio-political issues, and is each of your artworks an act of resistance against all forms of oppression and injustice in the world?

CD: Precisely. My work as an individual is only a little part of a larger collective resistance against oppression, broadly speaking.

TLmag: Textile art and embroidery have been historically dismissed as “women’s work” and “craft”, yet they are a powerful medium for storytelling and communication. What do you like about working with embroidered fabrics, and why is this medium an ideal way to convey your vision?

CD: The use of fabric is double edged: when stretched, displayed and lit in a museum hanging, it has a commanding presence, yet is somehow intimate. When folded, it can be covert, mobile and nomadic. The stories should outlive the materiality of the work. The textile pieces we make are not the sole bearers of the narratives we echo.

TLmag: What role do words and language (English, Tagalog, Latin, etc.) play in your artworks?

CD: The use and misuse of language is a tool to define specific cultural cues and dimensions. Like any visual element, words add new layers of meaning into the work.

TLmag: Take me through your creative and production process.

CD: I barely have an established method of production. I have set collaborators for specific tasks like embroidery or wood sculptures, but I work with different organisations and individuals for research. I primarily consult with peoples’ organisations and activists working on the ground. The work that happens in the studio becomes a reflection and an extension of revolutionary practice.

TLmag: What are the greatest challenges you face when creating your artworks?

CD: The contradictions in contemporary art.

TLmag: What is the role of the artist in society?

CD: Artists need to keep learning by immersing themselves in the stories of others. We need to condition ourselves to an extreme empathy and continuously strengthen solidarities. As we develop our practice, we should also deepen our connection with everyone else. Cultural work should never be isolated from the rest of society.

TLmag: What new projects are you currently working on?

CD: I am currently working on some projects that visualise the conditions of a semi-colony.

This interview originally appeared in TLMag35: Textile/Tactile/Texture

All photos courtesy of Cian Dayrit