David Salle: Composing American Images

American artist David Salle shares the secret behind his practice, approach to iconography and connection to the East End of Long Island.

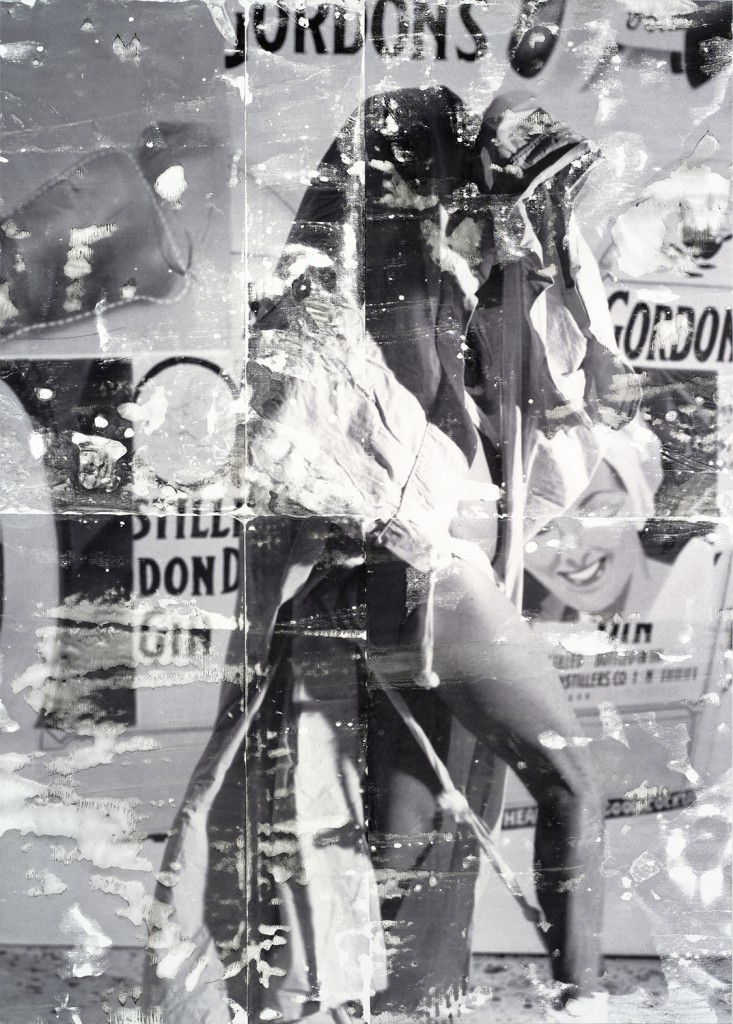

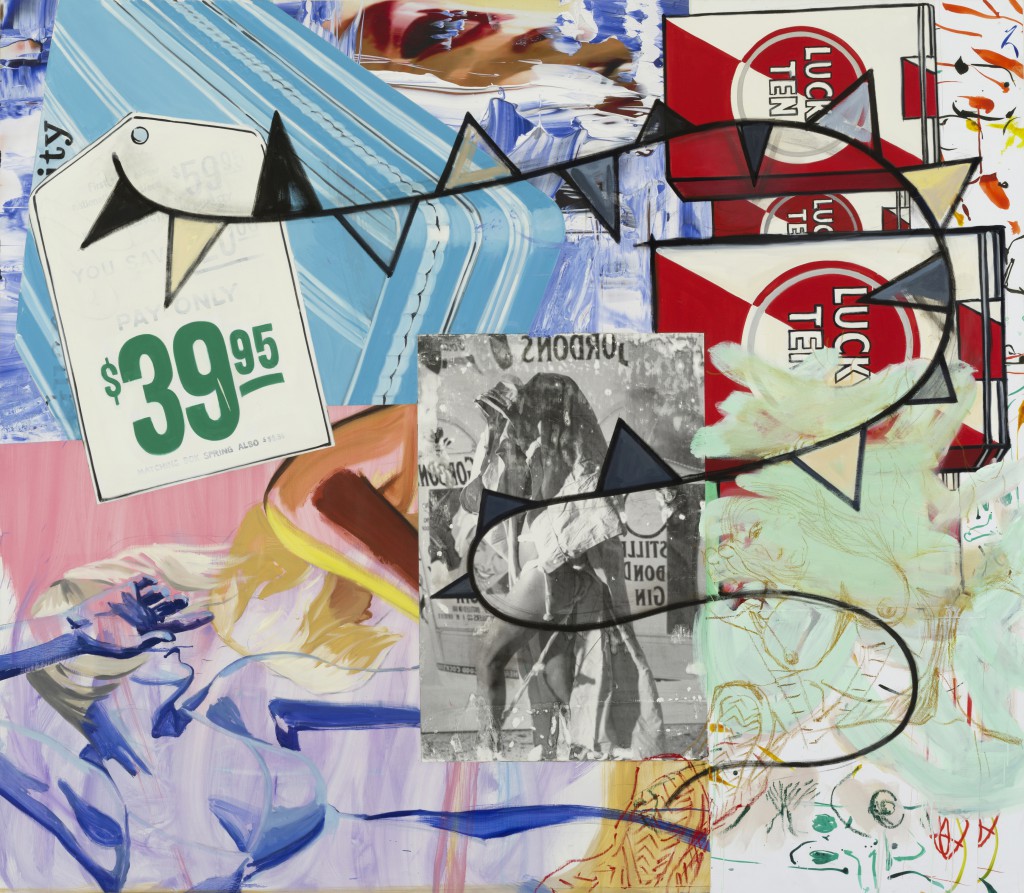

American art’s soft-spoken maverick, David Salle has made waves since first coming on to the scene 35-years ago. With major retrospectives held at the Whitney Museum in New York, Amsterdam’s Stedelijk and the Guggenheim Bilbao, his iconic large-scale compositions are recognised the world over. His all-encompassing-cum-dynamic approach has also been seen in set design and film projects. Often mis-labeled as a forbearer of postmodernist and neo-expressionist movements, he identifies himself more in the great modernist tradition, first set in motion by abstract expressionism and the New York School. In an exclusive interview with TLmag, Salle describes his method as an evolution starting in childhood. Prefacing our visit to many renowned ateliers spread across the East End of Long Island, the artist also talks about the secondary studio he’s maintained in the area since the early 1980s.

TLmag: As a child you painted “interiors populated by people.” How did you first develop your approach?

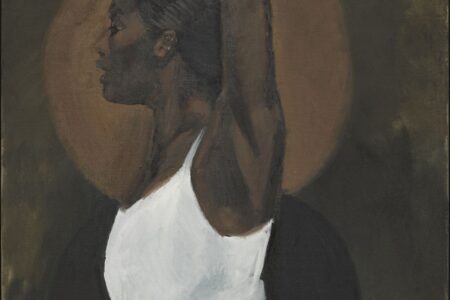

David Salle: When first learning how to draw, one looks at the body – but not the relationship between the figure and the context in which it exists. Early on, I had a teacher who emphasized locating the figure in space – making the so called background equally important in the total composition. She considered anything less to be unenlightened. This idea extended itself to the construction of pictorial space generally; that it was not simply a reproduction of reality. The figure, like value pattern, or light, became another element, something that could be privileged at different moments, but never isolated. As a nine-year old, these truisms had the force of a revelation. The things we encounter when young impact the rest of our lives; they can help determine a very long path.

TLmag: You describe your paintings as frames of reference where simultaneous disjunction can combine without becoming collage. How are you able to transcend the “weights and temperatures” of juxtaposition?

DS: One always looks at what’s behind an object; what holds it in place. You can push this idea one notch further by considering the wall behind or next to a painting. Single panels turn into diptychs or triptychs that can incorporate other elements in the surrounding space. This inclusiveness is based-on the notion that nothing exists as free floating space. As in life, objects in art are never solitary. What’s interesting is when things are brought into a certain relationship – one that sets off a refreshed perception or point of view. More and more, I see myself as a kind of orchestra conductor, or an orchestrator – determining which instrument should play which note, so that the ensemble sound expresses the right content.

TLmag: Early in your career, it was important that your work carry meaning. How did this shift to primarily addressing aesthetic treatment?

DS: Its natural – we all change over time. Certain things remain constant while other elements come and go, or are augmented, at different times. Change is a matter of emphasis. When artists are young, they’re concerned with meaning in their work; the last thing they want to do is create optical sensation. They tend to mistrust taste and sensibility, trivialize it. As you get older you realize that the optical is sort of all we’ve got. And, after 40-some years, you no longer worry about meaning as such, because you know that it’s already there – that it can’t help but be there. Your focus shifts to constructing the best possible picture.

TLmag: Working on the East End of Long Island, what do you pull from its artistic heritage and position as a measure of American art? Do you consider yourself as part of this lineage?

DS: Though I identified myself with the mythical “New York School” from an early age, I studied at CalArts. Even though we were in the California desert, most of my teachers were descended from this tradition. The summer after first arriving in New York, I took a bus to East Hampton and visited the graves of Jackson Pollock and Frank O’Hara in the famous Green River Cemetery. These were people who already meant a great deal to me and who influenced my identity as an artist. I came out east to breathe the historical air, so to speak. That tradition was real to me. In those days, the Hamptons were still somewhat rural; not overrun by mansions. Artists would rent part of a farmer’s barn, rig-up an outdoor shower, paint all day and sleep on the floor. Meeting other artists and writers of my own – as well as the previous generation, who worked in the area was important to me. Its hardly news that artists need feedback. Painters primarily paint for other painters. Being in close proximity facilitated studio visits and dialogue in a natural way. Then things start to happen, people’s careers took off. Houses got bigger, but I never left. Eric Fischl, Ross Bleckner, Julian Schnabel and I all moved into various parts of the Hamptons at around the same

time. Then Lisa Phillips, Richard Prince and many others came a bit later. Though the area has changed – it hasn’t necessarily been ruined for the artists. And there are younger artists arriving still, which is great. Those of us who have been out here for a long time are practiced at ignoring the absurd bits. You learn to play a little mental trick to remind yourself of what it used to be like.

(originally published in TLmag 23, Spring Summer 2015)