Erika Verzutti: New World

For the A/W 2022 issue of TLmag38: Origins, Olivier Basciano wrote about the work of Brazilian artist Erika Verzutti and their relationship to nature, archaeology and time, while playing with motifs and themes about contemporary art and colonial histories.

I’ve always thought the final scene in Planet of the Apes, where the discovery of a decaying Statue of Liberty leads to the realisation that, all along, the film was set on Earth millennia in the future, could be extended. I’d like to see Taylor, the astronaut protagonist, venturing further through fully rewilded post-apocalyptic New York, stumbling over the ruins of the Chelsea gallery district, the wreckage of the Museum of Modern Art. What would all that lost art look like in the year 3978? What will rot? What will future civilisations try to preserve? If they ever take up my suggestion for one of the endless sequels to the classic 1968 film (Hollywood… it’s all yours), then Erika Verzutti could be drafted in for the set design.

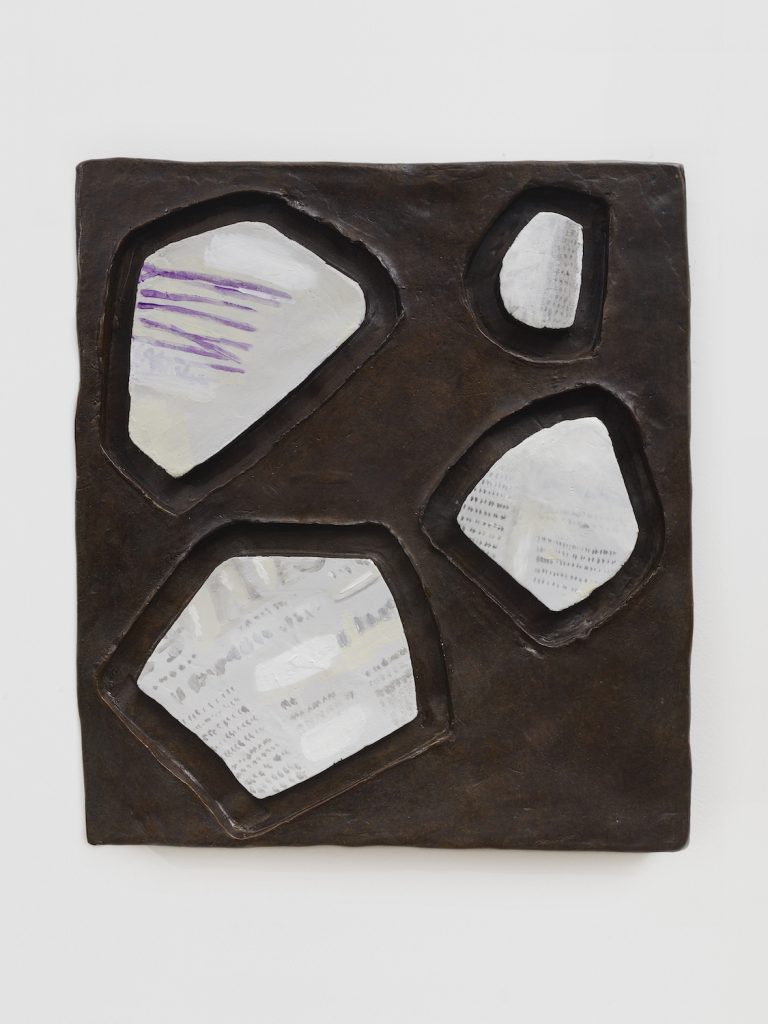

The Brazilian artist’s sculptures are, after all, reminiscent of treasures drawn from the depths of an archaeological dig: hewn in a variety of materials, from bronze and ceramic to papier-mâché and unfired clay, ranging in size and often painted, they seem vestiges of past civilisations. The surface of a typical Verzutti sculpture is mottled, rough and looks as if it’s been produced not by an artist in her São Paulo studio, but by nature, accident and time. Phoenix (2018) for example is a wall-mounted sculpture, in which the light grey papier-mâché plaque holds and contrasts lumps of dark natural rock clay and a white-glazed ceramic egg. 2 Boobs (2018) is similar in its organic qualities but dispenses the egg in favour of three bulging lumps lightly dashed with pink paint. The symbolism of the motifs – new life of the eggs, fecundity of the breasts – compound the ageless quality. Past or future, some things never change.

In other works, the presence of human touch is made clearer. Take Nude Slime (2019), a wall-mounted, roughly horizontal, lump of bronze: across the bottom half of the blotched surface six finger-like crevices are dug into the surface of the metal, the indentations painted purple with acrylic. Yet far from being a signature of the artist, there is something universal to the gestures (who doesn’t see some malleable and soft material and want to leave some trace of yourself in it). It is as if we are witness to the sliding digits of some unknown figure, their markings fossilised. Gold Used to Be (2020) goes further. On a ceramic plaque, a hand print appears indented alongside a series of attached aluminium cast seed-like forms. The forms cut into the surface of Dark Matter (2016), a papier-mâché and Styrofoam sculpture, are more cryptic and abstract, an opaque hieroglyphic language of circles and dashes. Similarly sublime is Branco (2016), a vast cosmological work that one could sit in front of for hours without ever quite taking in its entirety. Nine metres in length and over three in height, it is an abstract vista – though one might fancifully identify a night sky of planets and solar systems – painted in oil on papier-mâché and expanded polystyrene.

Throughout her fifteen-year career, which has exploded in recent years after a 2019 retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, followed by two more institutional surveys in 2021 at Nottingham Contemporary in Britain and on home turf at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo, Verzutti has also made references to art history in her work. Her practice, if it has a manifesto, is a testament to human creation. Tarsila with Koons (2015) features a shiny blue egg, reminiscent of a slick Jeff Koons sculpture, nestled in a three dimensional rendering of the monstrous phallic landscape shown in Tarsila de Amaral’s surreal 1929 landscape painting Setting Sun. Marshmallow Amazonino (2019), plays with Lygia Pape’s Amazoninos (1989–92), bronze copies of the titular squidgy sweets mounted on a black plaque. Likewise, Torre de Cacau (2021) is a bronze freestanding tower, over three metres in height, of seemingly balanced coconuts. This homage to Brancusi’s Infinite Columns is tempered by a knowing reference to the exoticism of the fruit depicted, a nod to the tangled colonial history of Europe and Brazil.

At the recent third Geneva Biennale Sculpture Garden, the artist exhibited an over two metre outdoor bronze titled Venus of Cream (2020), part of a series of works she has made riffing on the Venus of Willendorf. The object, all bulbous and lurid, is as cheeky and brimming with humour, as the name suggests it might be. Opening concurrently at Andrew Kreps in New York was an exhibition featuring more re-imaginings of the Venus, the tiny fertility figure, believed to date back 25,000 years, unearthed in Austrian soil in 1908. Moulded from fruits, the bulbous bottom cheeks and breasts of the original are abstracted into the combined forms of melons and the like. Like Planet of the Apes, Verzutti’s work requires a sudden temporal shift in perspective from the viewer: though her sculptures might seem the last glimpses of a past lost, they also celebrate and make obvious their process of production. Simple gestures, be they finger print of Nude Slime or the juxtapositions of Tarsila with Koons, have a sense of joy to them. If our ancestors worshipped the Venus of Willendorf for fertility, then Verzutti’s sculpture might equally offer new shrines to creative gestation, the art of the simple act begetting some new life.

@erikaverzutti

@ fortesdaloiagabriel

@andrewkrepsgallery