Frederik Vercruysse: Looking for Balance

TLmag catches up with interior and architecture photographer Frederik Vercruysse, whose latest series of everyday still-lives shows a shift towards the subjective within his oeuvre.

Clean geometric lines and stark shapes are hallmarks of Frederik Vercruysse’s photographic work. His minimalist, ethereal style and the graphic dimension of his photographs have allowed him to build a successful career as a photographer in design and architecture circles. For Tlmag 33, Frederik contributed a surprising personal series comprising of everyday still lives photographed in his home titled ‘Silent Object, Still Interiors’. We caught up with Vercruysse to learn more about his lasting fascination with architecture, what led to his shift to producing still lives and what it means to go beyond the “perfect” manufactured image.

TLmag: In your bio you say how you became attracted to architecture, and photographing architecture, after studying photography in Belgium. Could you elaborate on that?

Frederik Vercruysse (FV): Since I was a teenager, I already knew what I was going to become: photographer or architect. Photographer to improve the world with social photography, my romantic idea of being photographer… Or architect to build. I became a photographer and started to shoot architecture. The perfect combination. I am glad I became a photographer. I have too little patience to work on the same project for 5 or 10 years.

TLmag: Do you feel that there are any similarities between the practice of architects and that of photographers? (Or if anything, something that you wish more photographers applied in their practice that you see in architecture?

FV: Since I am not an architect, I am not sure about the similarities or the differences. What I can say is that when two practices deal with sensitivity to light, shape, color, material and context, and imaging in general — it isn’t a surprise that they show great similarities. In photography you have a concept phase (with or without a customer), there is a pre-production phase, after that there is a creative phase and a post production phase — ending with a “show” moment, that is ultimately the goal of photography. Having said that, it seems to me that as a photographer you can also only work in the creative phase, and skip the rest. In architecture – that doesn’t seem possible to me. The ‘instant’ness of photography is a given fact; even when the concept is completely thought out — the action is mostly entrusted to your gut feeling as a photographer. In architecture, everything is more based on long term projects and concepts, and you can’t be as spontaneous I think.

TLmag: Your foundation in architectural photography has allowed you to shift focus towards interiors, still life and portrait-based photography. What caused this shift?

FV: As a starting photographer I was mainly involved with documentary photography. Registering an architectural project. Often quite “objective”, sometimes with my own accent but always quite distant. Since a lot of good architects in Belgium also very often build houses and not only large construction projects, I automatically ended up in interior photography. In the beginning, this was also documentary, because I thought it should be that way. After a while, I ended up with a series in a glossy lifestyle magazine and I started making more interior features than architectural ones. Technically the same approach, but with interior photography, you can still create more atmosphere and there is a different aesthetic and substantive story to tell. In architectural photography, it is still very popular to photograph from quite a distance.

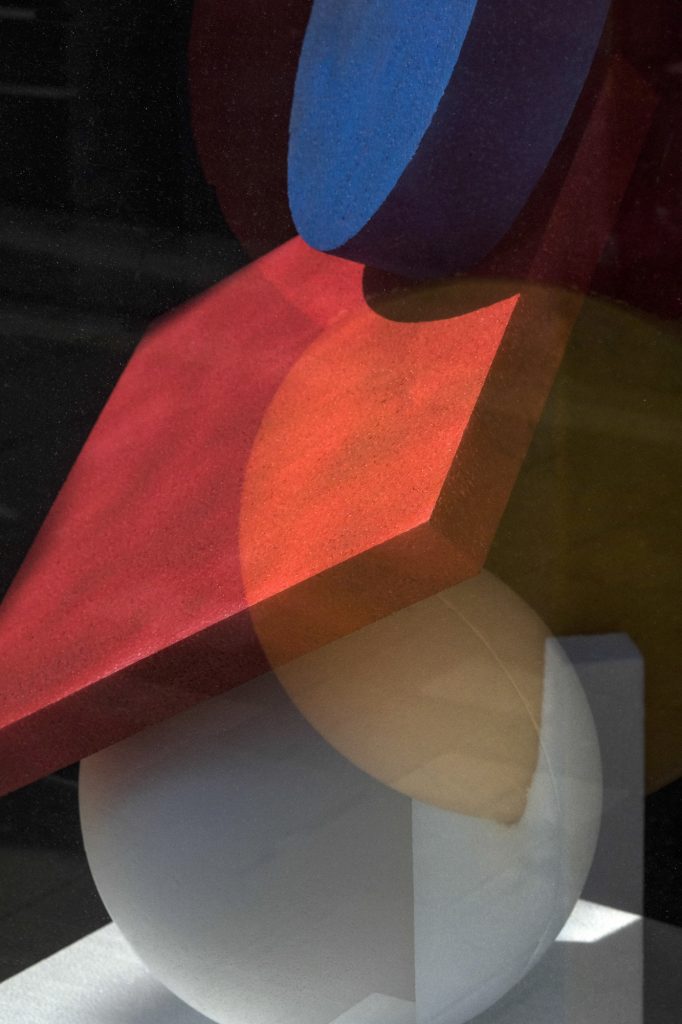

Six to seven years ago, I started to get an itch to create: to get closer, and be much more involved and create the shapes and colours, and lights in my images. When making still lives, the set dressing is the important thing that you need to focus on. When I did that myself in the beginning, it was almost as though I was ‘playing the architect’: building at a micro-level. Currently, I work with set dressers and stylists and it feels less like that, now its more about building that abstract imagery. This step was a goal, along with abstracting objects and taking them out of their daily context. It was also about discovering the possibilities to create light yourself instead of having to constantly seek it out and register it. Ultimately, still life photography shows many similarities with architectural photography. It’s something for the non-spontaneous photographer with an eye for detail.

TLmag: At the same time, your series ‘Silent Objects, Still Interiors’ doesn’t feel very stylised, the settings just seems as though they were found that way and were well observed. Could you tell us more about it?

FV: After graduating, I started shooting for architects and magazines quite quickly. I had never really explored that very much: I found it a challenge to deliver technically perfect imagery and to look very closely to the reality and then register this as objectively as possible. Ultimately, subjectivity creeps into the oeuvre after a while, because you develop your own style. That actually happened very unconsciously to me. I still really love to do documentary and lifestyle photography for my commercial assignments, but I am also starting to ask myself too many questions. More specifically, questions about the consumption of architecture and design. This work started by photographing everyday objects, and not with products that had to be sold. For ‘Silent Object, Still Interiors’ I felt like doing personal work with the settings that I prefer to photograph: interiors and architecture. To approach these everyday objects in the same way that I would a commercial assignment. I think this series should be a start for new work. Maybe even a new chapter…

TLmag: The images in this series feel very personal, as though you’re first seeing/experiencing your everyday environment through your photographs. As this series is ongoing, how has lockdown impacted this work?

FV: I started the series ‘Silent Objects, Still Interiors’ at the beginning of this year, just before the lockdown. The intention was to shoot a lot, but that was only partly successful because I also wanted to photograph at many people’s homes. In these times it’s not that easy to visit people. I only photographed for a while at home and in the city. The lockdown forced me to look in another direction. It was a tool to look differently, to avert my gaze from my way of looking at the city, interiors and architecture in general. And of course, there was a lot more time to think about those things and to reflect.

TLmag: In your text that accompanied the series in TLmag 33: The New Age of Humanism, you stated how the images that you were prompted to create in the past were influenced by capitalistic tendencies that prevail within the architectural and design world. What is the function of photography, within those fields – how do you think this series goes against or informs about those tendencies?

FV: Obviously, photography is a very important marketing tool for architecture and design. However, I don’t want to look for absurdities or a “photogenic chaos” of mass consumption — as this often gives an oversimplified answer that usually represents the opposite of what I’m aiming for. I am interested in the positive power of architecture and design, and want to look for a way to create poetry with what surrounds us – with all its exaggerations, mistakes and flaws.

This is what I tried to do with my still lives: creating poetry with everyday objects. It’s not the perfect “pinterest” image, the perfect view or the ingenious tower that I am looking for. I want to translate what I see and how I feel about it. In this work, I am simply questioning these tendencies: it’s a bit like a love-hate relationship. That’s a feeling that I’m not sure can be translated into photography. These questions are a tool to take a critical look at what I’m making. To really counter the sentiments I had written down completely, I think it would be better to stop shooting interiors and architecture at all. It’s like walking on a tightrope, and looking for balance.

This interview is an extension of Frederik’s article in TLmag33: The New Age of Humanism.

https://www.frederikvercruysse.com/