Gold and Religious Rituals: The Cult of Syncretic Material

For our S/S 2022 issue, TLmag37:State of Gold, guest editor Marco Sammichelli wrote about how many contemporary items associated with religion and ritual are moving away from gold into more modern materials, but that gold’s power will always endure.

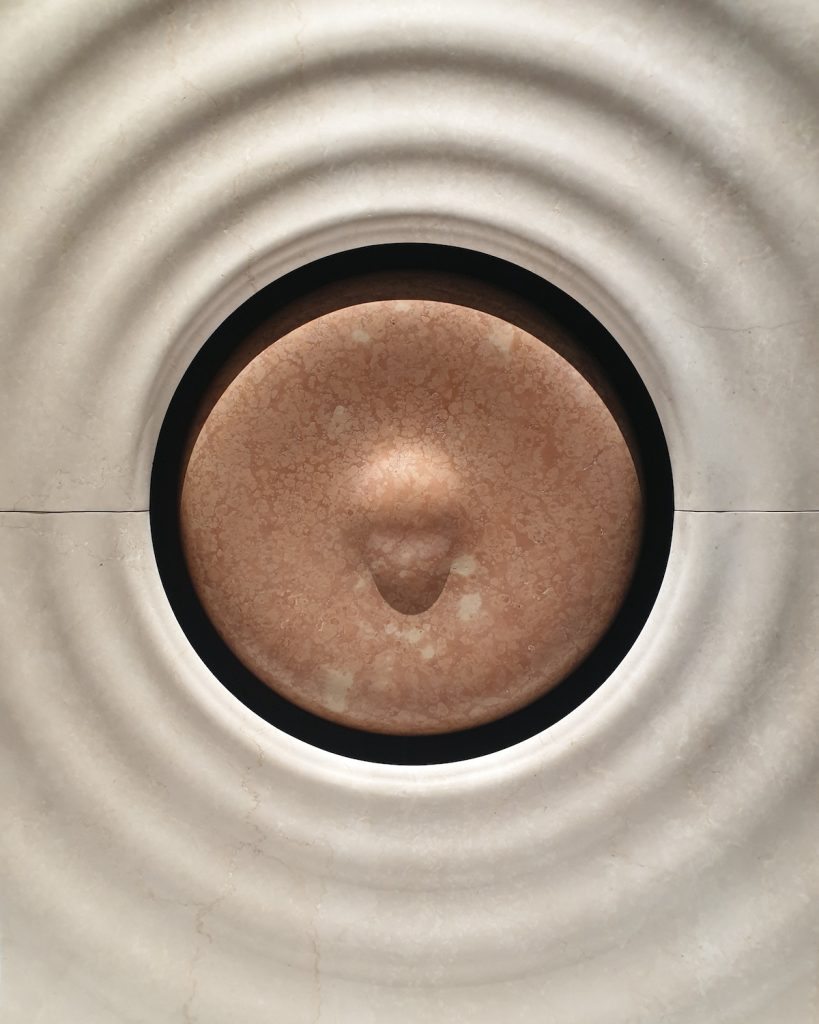

In the oldest monotheist religions, the use of gold was a constant. The value of the material was part of a message, one which needed to communicate the concepts of unity, power, charm and mystery. There is no church, mosque, synagogue or temple in which gold is not a decorative architectural element, or the protagonist used to create the ritualistic instruments, the icons of devotion, the focal points of liturgy or the ceremonial garments.

However, modernity seems to have definitively marked the fate of this material; with its rarity and redundancy, it is no longer used as much by artists, architects or their clients. And yet, gold has such deeply rooted traditions that it has not quite disappeared from the landscape of places of worship. On the contrary, its decline has been delayed precisely because of the consoling weight of the material’s rhetoric. God is light, sun and fire, and gold is the colour that best represents him: because it dominates darkness and manifests an immediate and comprehensible ideal of beauty. The gold melts within the symbol, which in turn becomes the driver of the ritual.

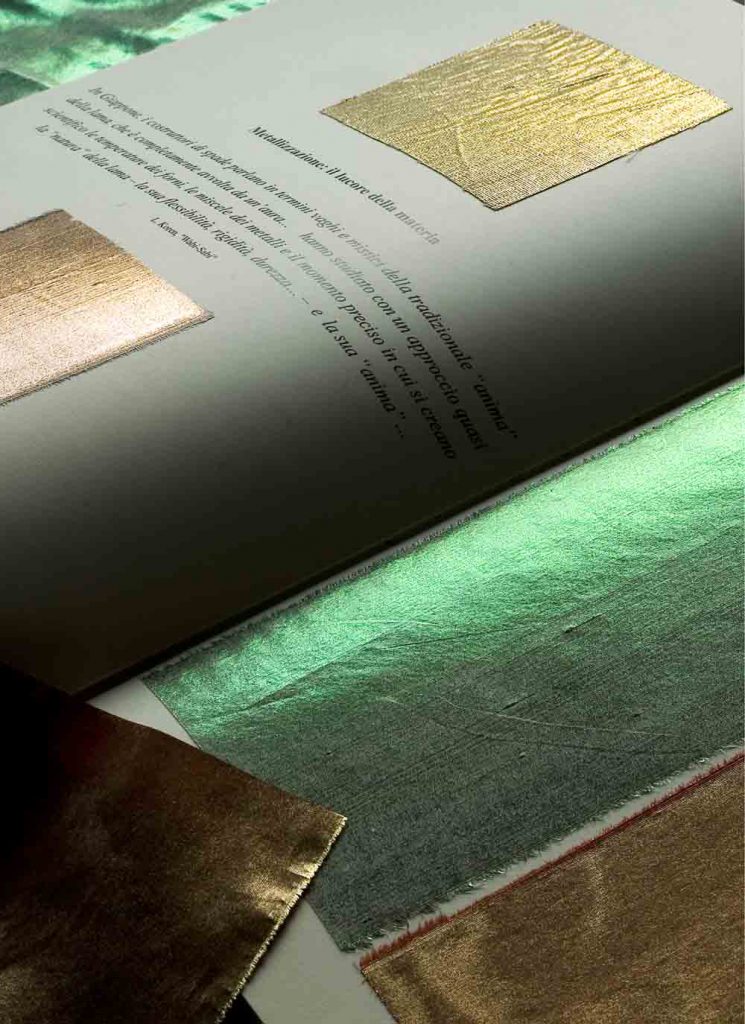

Among the most striking examples ever dreamed up by a creator is the work of textile designer Nanni Strada for the liturgical chasubles featured in a 2005 exhibition in Vicenza, Italy. Belgian theologian Julien Ries wrote that “the symbol is the orientation and principle of movement, the bearer of meaning, and the unifying force of the invisible and the visible. It constitutes a laboratory of energy with inexhaustible virtuality”. So much so that for some time, designers and artists have used the ritual to imagine enterprising ways of rewriting codes, materials and relationships, while respecting the message.

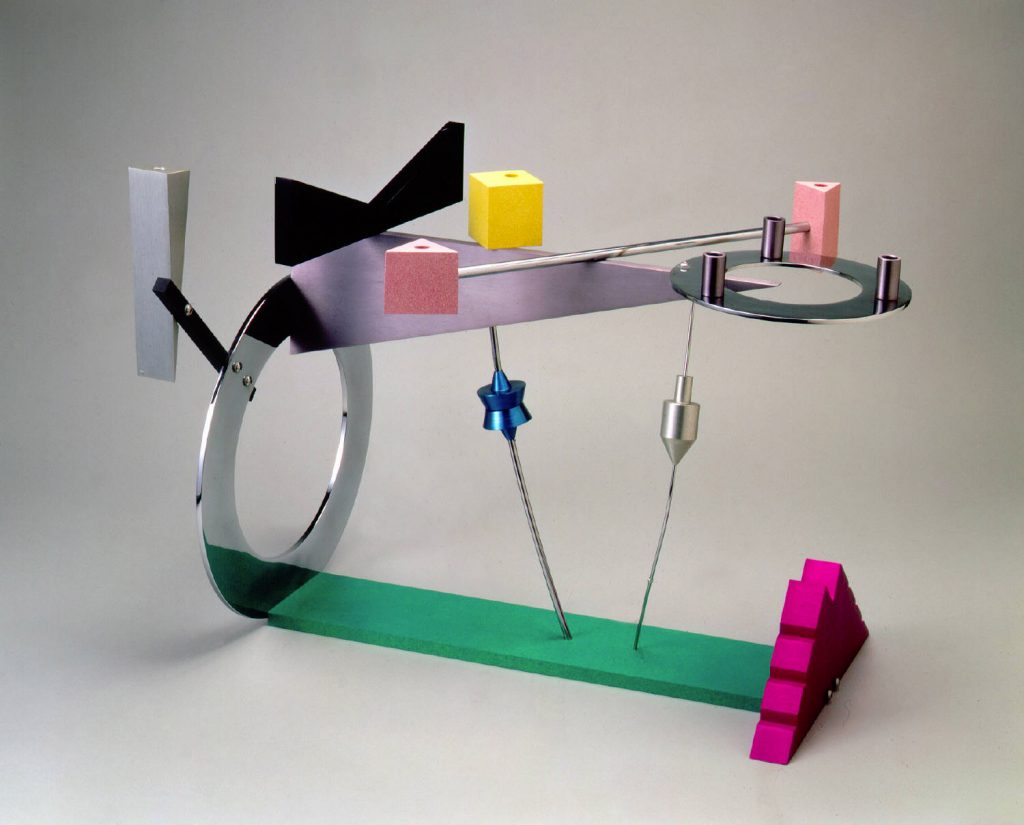

Another story relates to the set of objects that accompany traditional Jewish rituals, which has been the subject of experimentation since the 1980s. The drivers of this reflection have not been individual designers, but rather institutions such as the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, which collaborated on editions with Achille Castiglioni and Peter Shire, and New York’s Jewish Museum, with exhibitions such as “Reinventing Ritual: contemporary art and design in Jewish Life”, in 2009.

This last initiative, curated by Daniel Blasco, had the task of shaking up a consolidated panorama, and in particular of reopening the debate on the formal manifestation of the spiritual encounter through an attitude aiming at absorbing contemporary themes. This notably includes recycling, gender politics, and the relationships between different ethnic communities, which can be found in the classic and always disturbing works of Lella Vignelli, JT Waldman and Martin Wilner. Rethinking ritual tools in this light offers design and art new possibilities for mediation; they are challenges to the rhythm of information.

Don Giuliano Zanchi, theologian and director of the Diocesan Museum in Bergamo, is clear on this point, maintaining that “the linguistic horizon frequented today by the aesthetics of lightness has at least been and gone. This is a fact that is even embarrassingly obvious. The glittering costume jewellery of church interiors and artefacts does not testify to a communication strategy but to an uncertain identity.

Today’s Catholicism needs axes that keep it in an authentic alliance with man. Design creativity is certainly one of them. But the instinct of a creative world that is easily brought to address church matters with the bland attentions of a higher subject, inclined to mechanically apply pre-established criteria, disinclined to rephrase its questions in the presence of other intentions, to integrate the aesthetic expectations of different forms of experience, does not bode well either. The symbolic experience at play in the sacred space requires aesthetic solutions that cannot simply be replaced by the automatic import of standards or models from a commercial catalogue.”

Reminding us of the continuing validity of this approach is a precious object that can be found in a splendid museum dedicated to sacred art, designed by Peter Zumthor in 2007. “This small crucifix from the 11th century, now in Cologne’s Kolumba Museum, is truly a one-of-a-kind object,” explains Riccardo Falcinelli, a specialist in colour and visual communication. “The body of Christ is cast in metal, while the head is made from a lapis lazuli portrait dating from the first century: so more than a thousand years old.

This is a typical choice for a goldsmith, just like setting a hard stone in a metal support. But there is more to it: the Hellenistic head is a woman’s face, mounted not only on a male body but on that of Christ. For the anonymous medieval sculptor, the conflict of sexual genders, the contrast of materials and colours (golden body and blue face), is neither alienating nor outlandish. What matters is the overlay of an ancient and precious colour on a modern base, which makes its spirituality meaningful. In short, the face of Christ exerts a spell that makes sense, because it is expensive, prestigious, and distant.”

This piece, commissioned by the Archbishop of Cologne in 1049, is known as Herimann’s Cross. The female head in lapis lazuli placed in the place of the face of Christ is an extreme and enigmatic testimony to the practice of reusing antiques that was already fashionable in the Middle Ages. Although the current state is not original, this work is like other crosses of the time, yet at the same time is original thanks to the choice to complete the body of Christ with a female head.

The face of Christ/the woman attests to an important fact: a truly surprising absence of scandal and conditioning for the time. The relationship between them and the black is an often-recurring theme in Islamic iconography. Here too, yellow gold is synonymous with light, while the combination of green and black is considered sacred, is found in alphabets and scriptures, and appears systematically in the mathematics of mosque shapes.

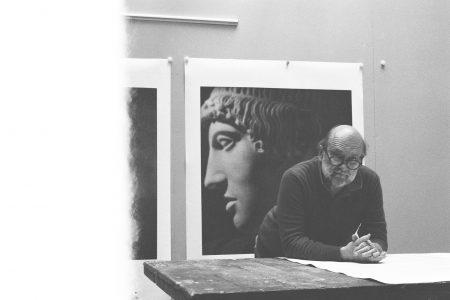

Sufi mystic, psychotherapist, Quranist and artist Gabriele Mandel Khan produced boundless literature on these themes, inspiring other artists such as Jean Cocteau and Henri Matisse in Europe and the Middle East, as well as designers including Isao Hosoe and Lorenzo Palmeri, precisely because of their ability to retain the aesthetics and architecture of thought. When mathematician and theologian Pavel Florensky published his essay The Pillar and the Ground of Truth, in 1914, he wrote that “no formula can encompass all the fullness of life”; the mystery of the sacred is not the result of the impoverishment of the vital experience, whether by ignorance or oppression, but rather more radically by the excess of life, with its multiple and contradictory manifestations.

Florensky continues: “The closer one is to God, the more distinct are the contradictions.” The various monotheistic religions put the meaning of the sacred into objects, colours, shapes and specific moments. In this perspective, thanks also to the logic of the arts, the sense of the sacred and the right exercise of reason point in the same direction. Almost as if to prove that the more one uses reason, the greater the sense of the sacred.

Algerian artist Adel Abdessemed, in exile in the United States, found a provocative antidote in a work that is powerful because it is syncretic. “God is Design” is a video animation based on more than 3,000 black and white drawings of ornamental motifs and symbols from the three major monotheistic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), as well as graphemes referring to the morphology of human cells. Frenetic patterns and reconciled differences, but also acquired certainties that cancel each other out.