Ups and Downs of the Guangzhou Triennial with Angelique Spaninks

We catch up with Angelique Spaninks, co-curator of the 6th Guangzhou Triennial, to discuss biotechnology, digital realities, censorship and the practice of international curating

Data stored in the DNA of shiny soapy bubbles. Cloud machines. Semi-autonomous robots. A room that shrinks you or turns you into a giant. An immersive scientific laboratory full of strange objects and images.

These are just a few of the intriguing and thought-provoking sights that visitors to the 6th Guangzhou Triennial will find themselves confronted with. Hosted at the Guangdong Museum of Art, the exhibition reflects upon the implications of developments and progress in the digital and biotechnological worlds.

The exhibition’s title ‘As We May Think: Feedforward’ references the 1945 seminal essay by American engineer Vannevar Bush titled ‘As We May Think’ in which he imagined a universal communications apparatus which he called a Memex. He predicted that this machine could store and easily share all the world’s information. Just a few decades later, we are living in Bush’s imagined reality with the internet touching each and every aspect of our lives, morphing and shifting how we live in the information and Anthropocene age. Co-curator Angelique Spaninks tells TLmag “Using the ‘As We May Think’ essay we thought we could apply it to this century and see how technology and culture are developing now.”

Exploring this idea are three sections of the exhibition by three international curators. The first section Inside the Stack: Art in the Digital curated by art historian Philipp Ziegler explores the fundamental questions of the digital space as a new form of reality. It looks into the past, contemporary and speculative future versions of the digital world as conceived by artists. Section two, Evolutions of Kin, by Eindhoven-based curator Angelique Spaninks considers the ethical conundrums of technological invention and intervention and considers what it means to consider humans and non-humans on an equal level. The final section, Machines are not Alone, acknowledges the plural meanings behind the word ‘Machine’ and considers the natural environment as a form of machine with systems, ecologies, thoughts and relationships. Chinese/American curator ZHANG Ga imagines a radical rethinking of what it means to be post-human in a world of machines.

Logically, one would expect these three sections to be split across the three levels of the museum but Spaninks explains “we decided quite quickly that we did not want to split the sections across the three levels. It would have been very easy to say “each gets their own level and you can do your own thing”, but from the start we wanted it to grow organically together. We think it is very important that these lines of thought weave together over all floors and therefore considered how we could arrange it so that it becomes one story, with different chapters that refer to each other. It made it quite an organic curatorial pressure cooker process.”

Despite the organic nature of the pieces and visions coming together, the curatorial process was complicated when, three weeks before the Triennial was set to open, five works were censored by the government. “Censorship is common in China but this was not clear to us and also not clear to the museum itself why the restriction happened,” said Spaninks.

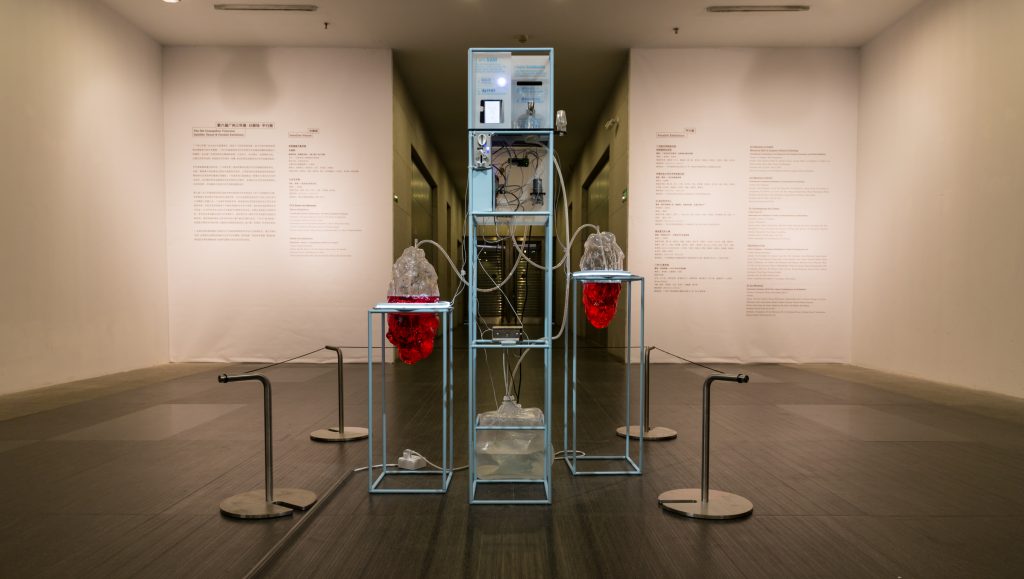

Works banned included American artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s T3511 which is a film about a post-genomic love story. The curators and artist suggest this may have been restricted based on recent controversies about Chinese Scientist He Jiankui who announced his creation of the world’s first genetically edited babies, a set of twins he made resistant to the HIV virus and was widely condemned for unethical and reckless practice. However, Lynn Hershman-Leeson’s laboratory-like installation entitled Infinite Engine was still allowed in the show. It also examines genetic manipulation creating a scenario in which both the bright and dark possibilities of this biohacking can be considered.

Angelique Spaninks explains that the censorship “was very difficult for the museum because they are a state museum so they are part of the censorship system in some way. But I had the feeling that they were sticking their necks out to do something that was new and relevant and timely for what China is doing now from a cultural perspective and from a more general perspective with the ambition of China to become a world leader in science and in technology before 2050 or if possible before 2030. If you want that as a nation you should also be open to this more cultural and critical thought and these discussions about it and if you are not, then it becomes difficult.”

Reflecting on the extensive media coverage that the censorship caused after being covered by the New York Times Spaninks felt, on the one hand, it was good as it facilitated a discussion about issues of information control and cultural repression; however, on the other hand, it dominated the coverage of the exhibition in Western media and therefore the exhibition itself and its reception in China remained unexplored.

The Triennial is a unique event on the calendar of the Guangdong Museum of Art which usually shows more traditional artworks and caters to an audience used to paintings or more traditional contemporary Chinese art. Therefore the exhibition was both an opportunity and challenge to try something different with a lot of multimedia and installation based works. Spaninks recalls that she was pleased with the reaction at the opening which was “super eager” with “the 60 people on the tour staying for the full 2.5 hours wanting to know more and more”.

Works such as Arne Hendriks’ Incredible Shrinking Man, which explores the possibility of shrinking everyone down to 50 centimeters to solve earth’s problems and question the dominant rhetoric of growth as a measure of success, captivated the audience. Describing this piece in the show, Spaninks says “His whole research was there – 80 posters with a lot of reflections on them and a lot of scientific facts. But in addition, we also built an Ames room which looks like a regular room but it is distorted in ways that make it possible to experience shrinking quite literally. The optical illusion of the room is that on one side of the room you are really big and on the other, you are really small. That worked really well and all the visitors wanted to go in.”

The site-specific installation which was another bureaucratic difficulty as generally in China must be submitted 3 months before the exhibition. Working on-site “is not done there which I totally understand based on their control system but that is exactly how I want to work. I think it creates the opportunity to open up much more interesting experiments, thoughts and debates rather than showing what is already ready.” Spaninks also challenged the status quo of curating in China by including a range of artists and designers from young practitioners to very established ones and “more women than men because usually it is not the case” she noted that “at the opening, I was one of the few women there.”

The MacGuffin installation and film entitled The Guangzhou Wedding of Things was another work developed on-site, specifically for the ‘As We May Think: Feedforward’. In this piece, they staged weddings between Chinese and African objects to celebrate and highlight the communities present but often unacknowledged in the city. They sourced objects in collaboration with students from the city over a two week period. The objects collected included Joss Paper Lacoste Shoes, Nigerian Karaoke Mics, Guangzhou Anti Radiation Maternity Aprons and Chinese Wigs for the African market.

Dealing with the complex topics of digital spaces and biotech advancements, a dystopian vision is often the outcome. However, the three curators of the exhibition paint an entangled picture of these fields through their selection of works with ethical dilemmas, potentiality, possible complications and both positive and negative implications being explored by the artists and designers. Overall, Spaninks leaves us with a sense of possibility in her description of the thinking embodied in the exhibition: “You can tell the catastrophic and the dark sides of the digital and bio-technologic and I think a lot of art focuses on this side of it, but there is also the other side. The side of hope. It can change so much. That is, it can also change for the good.”

‘As We May Think: Feedforward’ will be on display until March 10

Cover image: Charlotte Jarvis, Music of the Spheres, DNA; soap solution; bubble machines, variable dimension, 2013 – 2015