Julie Richoz

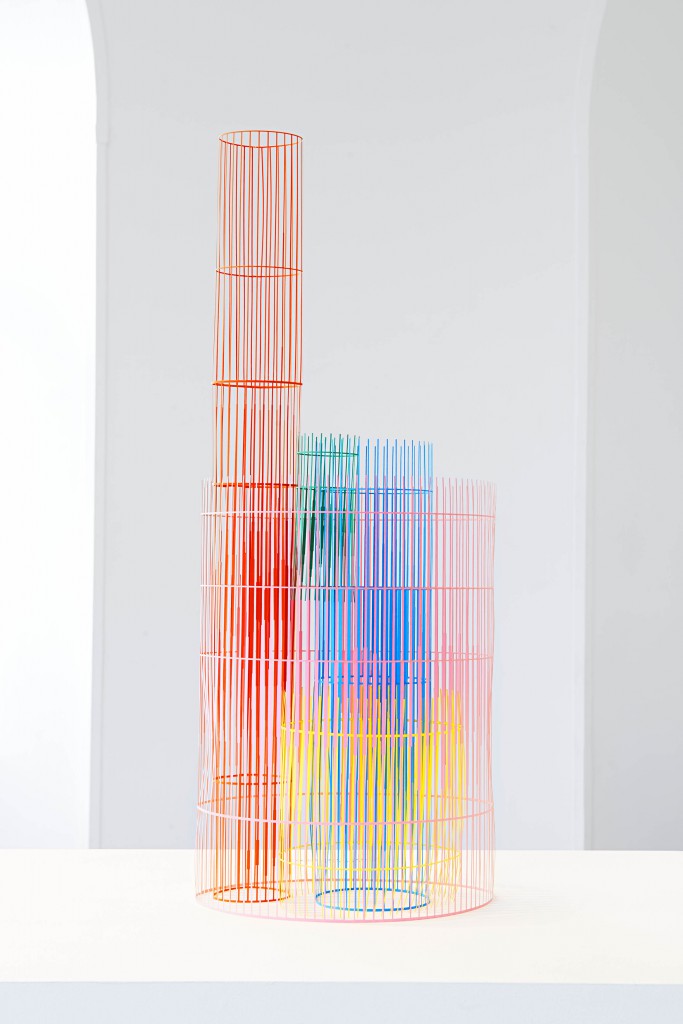

Allaying the presence of spring-steel in a delicately laced structure, the Thalie bowl for Artecnica echoes earlier speculative works like Armand: a series of paper cut-out cylinders that cover spectrum colour vibrations. Both are just a sampling of Swiss-French designer Julie Richoz’s ever-iterative oeuvre. The emerging talent has captivated the higher echelons of the craft-led design industry since establishing her own practice four years ago. Since then, she’s straddled the worlds of limited edition and contract market design; establishing a niche style all her own: bright colours and characteristic forms that challenge the convention of age-old materials, production methods and mandates to improve our everyday. Trained at the hallowed École Cantonale d’Art de Lausanne (ECAL) and with the venerated Pierre Charpin, the already prolific newcomer has garnered multiple accolades, including the 2012 Design Parade Grand Prix. TLmag spoke to Richoz about her practice.

TLmag: What first drew you to the prospect of design?

Julie Richoz: I’ve always felt comfortable with creative work. While other children played sports or danced on Wednesday afternoons, I attended art courses. Eventually, I put all my energy into getting into a special section of high school dedicated to the arts. There I discovered different practices: graphic and object design, architecture and fashion. I ultimately decided to pursue furniture. The field benefits from a large tool ‘palette’ used to express ideas, a range of materials, shapes, colours and contexts. Rather than spend all of my time behind a computer producing graphics, I opted for the more collective and manual nature of furniture design.

TLmag: How did studies at ECAL shape your interests?

J.R.: ECAL taught me to be rigorous and a perfectionist. The school has a ‘success-oriented’ approach, turning out fresh talent every year. ECAL’s strength is its growing network. During my studies, I engaged with influential teachers and imaginative students. Living and working in Paris today, I spend most of my time surrounded by fellow ECAL alumni. We’re almost like a Swiss mafia.

TLmag: Your use of form and colour shares some similarities with Pierre Charpin’s work. How did your apprenticeship with the Paris-based designer influence your practice?

J.R.: Pierre Charpin was my professor at ECAL. From the very beginning, I was attracted to his constructive approach. With an artistic background, Charpin’s focus has always been on materiality, colour, shape and proportion; a language of quality. We shared that sensibility early on. At the end his course, he offered me an internship that evolved into a three-year-long collaboration. Working as a small close-knit team, we had open discussions. Pulling from his experience, I was able to understand another generation’s perspective; how design has changed over time. This experience also trained me on how to run my own independent practice.

TLmag: Your work seems to reflect an understanding of form through geometry, mathematics, spatial voids, surface textures and logical aesthetics. From where do you pull inspiration for new work?

J.R.: It’s too easy to say that my designs derive from books, old Moroccan carpets, little chairs found at flea markets or even the Japanese philosophy of beauty. In reality, it’s hard to identify all the elements that lead to an idea. I rely on a mix of references; the blending of different images to achieve something new. Behind the influences that surround me, it’s important that I create my own narratives and material combinations. However, there are themes and formal elements that I continue to explore and that evolve from one project to another. I don’t see it as ‘recycling’ ideas but rather as a way to delve deeper. Sometimes an idea is strong enough that it doesn’t require that much ‘designing.’ But other times I have to conduct a lot research and refine the object step by step. Aesthetics follow a logic and in design, they simulate our surroundings. Though visual characteristics are defined by conception and manufacturing parameters, I like to push my designs even further while staying within reason.

TLmag: You’ve mentioned your affinity for Japanese design. How does this cultural reference interact with your Swiss background and appear in your designs?

J.R.: I travelled to Japan last year and discovered the context of objects I’ve long admired. They do every task – small or large – consciously and in ritual. Everything matters to them. Their quiet respectfulness is similar to the Swiss mentality. Japanese design is concerned with temporality; the aesthetic of fleeting moments. There’s a strong sense of simplicity and austerity that in a generous way, leaves room for personal interaction. These conditions strongly influence my work.

TLmag: What is the difference of working for and with semi-cultural initiatives like CIRVA, Sèvre, and InResidence versus commercial collaborations with Alessi or Artecnica?

J.R.: Residencies at CIRVA or Sèvres are valuable in developing a practice as they provide the time to create freely or conduct research. These experiences remain points of reference when I work on commercial projects. My role as a designer in these collaborations is to be a team player, working with others to realise a new product. The quality of discussion and varied input for different stakeholders is crucial. Recently, I worked with Danish heritage brand, Louis Poulsen, on a new Skyline pendant lamp, positioned for the contract market and mainly large spaces. This relationship was improved by the ability to work with skilled specialists. At the same time, a shared vision was important. The difference between cultural and commercial collaborations boils down to exceptions. The latter asks the designer to provide a service while the former provides one. I always try to balance both types of opportunities.

TLmag: What are you currently working on? What would you like to accomplish in the next ten years?

J.R.: I recently started a collaboration with Louis Vuitton. The world of fashion is unique with its own force of attraction. Developing physical products, this project has allowed me to explore new modes of expression. Other than that, I’ve continued working with different galleries and producing self-initiated designs. Ten years from now, I would like to have explored new professional experiences but still be working with the same approach I use today.