The Silent Call of Emirati Design

In terms of international visibility, Dubai-born designer Khalid Shafar is leading the pack: Czech brand Lasvit recently unveiled a prayer-inspired light installation, their first collaboration together

Dubai-born Khalid Shafar launched his design studio in 2010, with no peers around him. At the time, he had to explain to his fellow countrymen, unaccustomed to the idea of a local industrial designer, that his work went beyond that of a carpenter.

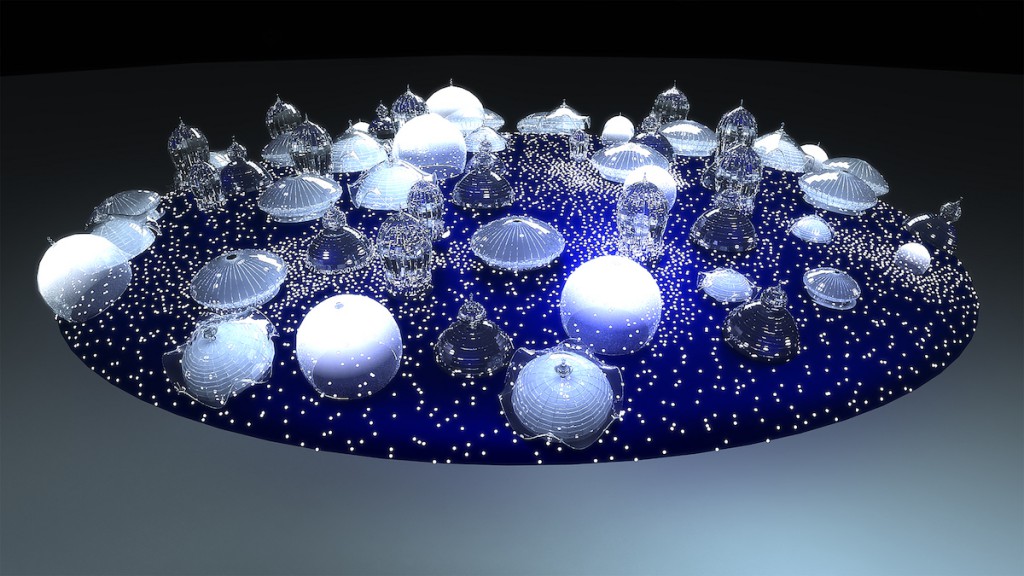

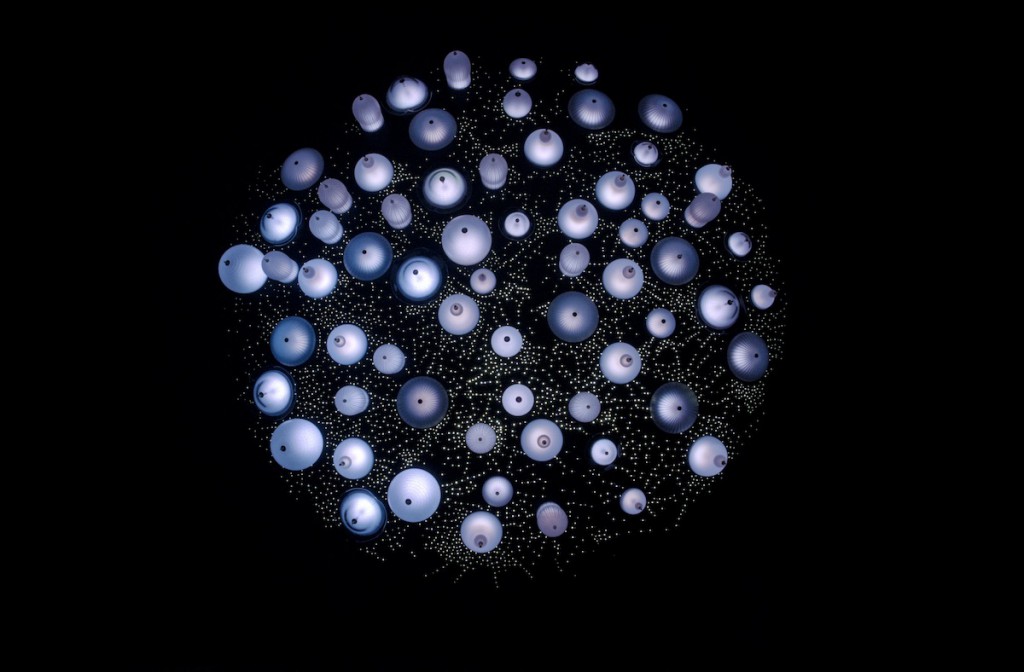

His bet paid off: his list of international collaborators now includes the Campana brothers, Kartell and Moissonnier. Recently, Lasvit became the latest name on that list: during this year’s Dubai Design Week, the Czech glassmaking company unveiled Silent Call, a dynamic light installation conceived by Shafar.

Dubai’s skyline has often been accused of mimicry, superficiality and ignoring the genius loci; Shafar responded by proudly devising a multicoloured textile pattern inspired by the outline of the Burj Khalifa. He turned the headbands of the traditional male attire into a room divider, the trunk sprouts of the endemic palm tree into a furniture collection and the conventional custom of sitting cross-legged into a lounge chair.

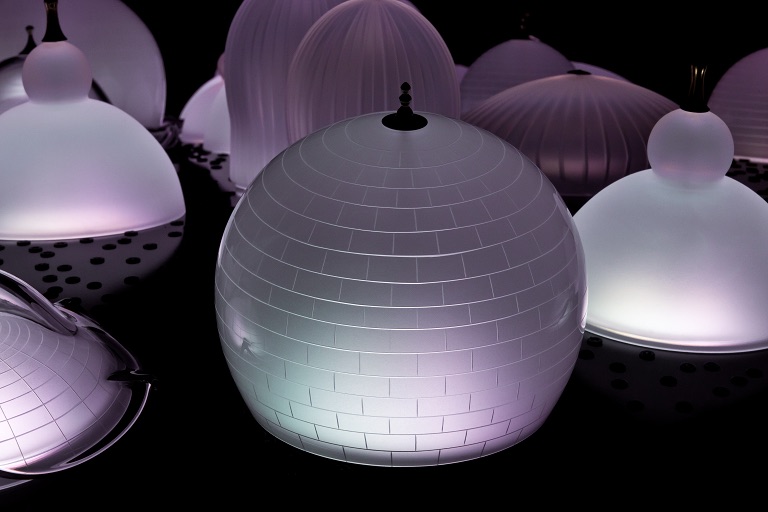

Silent Call is a continuation of that modus operandi: the designer turned the domes of five mosques around the globe -the UAE, Russia, Malaysia, Germany and Denmark— into an installation that, according to the tenets of Islam, calls for prayer five times a day. In Muslim countries, salah times are announced by the cry of a muezzin from a mosque, but Shafar and Lasvit devised a timing, dimming and chromatic system to turn voice into light. As he explained, the main audience is “travellers and worshippers who are inside buildings where calls to prayer may not be heard.” It is, just like Dubai, a piece that negotiates Islamic principles, an influx of global outlooks and adventurous building technology.

We spoke with Shafar about his mission as an Emirati designer, the importance of an educational initiative like the DIDI school and the future of the MENA creative scene.

TLmag: Given the current political mood, why did you think it was conceptually important to include references to the Muslim communities in Germany and Denmark in the piece?

Khalid Shafar: My choice of referencing the mosques in Germany and Denmark was not supporting any religious communities or beliefs. I was simply focusing on Islamic architecture as a pure architectural movement that inspires designers across the globe, and the mosque being its crown.

My selection for all five mosques was due to the unique shapes of their domes, that collectively present an appealing composition. Silent Call is not a religious installation; it’s a universal work that engages people from different backgrounds and cultures rather than focus on a particular religious group. The calling for prayer program function integrated within Silent Call was chosen due to my observations of our current busy lifestyles, and individuals needed to be reminded by prayer times.

TLmag: What type of feedback have you heard about the emotional impact of pieces such as Silent Call and Win, Love, Victory?

KS: Some connect emotionally with the pieces and others conceptually. For Silent Call, the attachment and interaction between the audience and the installation was beyond emotional. Even if individuals didn’t perform such prayers, they highly appreciate the concept and thinking behind the function. This makes some appreciate design and understand how design contributes to life enhancement and can support individual needs.

TLmag: You’ve said before that the local market didn’t quite understand what your work entailed. How have you helped change that perception about product design since you started?

KS: My persistence and pursuit to continue what I started in 2010, as well as my continued supply of creative work within my domain, have helped educate the same audience that once considered me a carpenter and now appreciate me as an international design practitioner.

I made sure to present, showcase and create works that challenge my audience and invite them to rethink the design process and its importance. An example is The Nomad installation, which delved in old architecture methodologies and brought back historical references into today’s lifestyle. It challenged architects today and the way they reference old architecture through a sole aesthetic approach rather than a functional one.

TLmag: So, do you see any short-term changes in the global horizon for MENA-based designers?

KS: We’ve had the fast growth of major destinations and events like Dubai Design District and the up-and-coming design weeks across the region, such as Dubai, Riyadh, Beirut and Amman —and let’s not forget the powerful impact of the major milestone that is the opening of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, as well as the creative year between the UAE and the UK. So I foresee definite changes and expansions for MENA-based designers in new markets and industries. Collaboration is a potential ride to the global horizon. My Silent Call installation, for example, is a great sign of international interest in the region and its creative force. Many more are soon to come.

TLmag: With d3 and its programmed expansion, as well as the Dubai Design Week, the Emirati design community is receiving a strong push –but right now it might seem like a cart-before-horse situation. How do you see it?

KS: I believe each [person and institution] has its own role in completing and contributing to this design ecosystem; that’s why I believe d3’s role is more about laying down the proper infrastructure for the community and the industry to grow and connect. It builds an environment that will encourage the creative force to work together to build a strong industry and supply more work on an international standard.

On the other hand, Dubai Design Week helps build design communities and audiences through education and events that contribute to raise awareness about design coming from this region. Design weeks also create trade and exchange opportunities between individuals, brands and organisations, and they are a platform for the younger creative force to showcase and expose their work to a wider audience within a specific period of time. The organic growth of any design community should be considered anywhere in the world, and time is a major factor in this. We need to be patient to reap the fruits —we can’t expect a well maintained design force ready in a speed similar to setting up a space or building a district. There is nothing wrong with having the cart while we prepare the horse to drive it.

TLmag: How do you think initiatives such as the ambitious DIDI school are going to contribute to this panorama?

KS: I think education is crucial in any industry, and design is no different. We didn’t have any solid in-house design educational programs that we could rely on to build up a creative force, the designers of the future. Most used to get some sort of design education abroad in Europe or the US [Ed’s note: Shafad himself studied in London’s Central Saint Martins]. With the establishment of DIDI, I hope we are stepping into a new era of design backed by education, rather than design stemming out of only passion. I am a strong believer in the idea that a designer should have some sort of design education before pursuing any design practice. With your design only, you can respond to a need or present a new “Wow!” product. However, with your design and your design education, you can do that and also educate and inform your audience and a future generation of designers.

TLmag: Over and over, your hometown has served as an explicit inspiration for your pieces. My impression during my first visit to Dubai was that its current iteration is more of a cultural importer rather than a raw creator. Why is communicating a loving-the-local stance such a big part of your design work?

KS: Your impression is similar to that of many who visit us from different parts of the world, and it’s logical, as the UAE is only 46 years old. We don’t have those historical and ancient buildings from old civilisations still standing within our cities as proof of our old existence, like major European cities do. Yet culture exists within the city lifestyle and its people, but it depends on how you define culture. For us, culture is how we used our past to live today and plan for the future. It’s different than history, and it’s more attributed to our local Emirati traditions and way of living.

As for me drawing from this in my design work, I believe that what for many is an unseen and unknown culture has not been exposed enough before. We have a treasure trove of inspirations that local designers could work with and export. With our new lifestyle, many old crafts and techniques are vanishing and I feel that my mission as a design practitioner is to maintain and sustain this, or at least preserve its story for the future.