Maria Lai: The Serious Game of Art

For our S/S 2021 issue: TLmag35: Tactile, Textile, Texture, Costanza Rinaldi wrote about the groundbreaking career of Maria Lai, a Sardinian born artist who used poetry and art as means to better understand life and its complexities, particularly as an independent woman of her generation.

“Behind me, I have thousands of years of silences, of attempts at poetry, of loom threads”. As a strong, independent woman, born and raised in Sardinia in the 1920s, when women were asked only to be a wife and mother, Maria Lai never allowed herself to be bewitched by great loves or trapped by traditions and customs. As her niece and heir, Maria Sofia Pisu, tells us today, hers was a true vocation for art, from the figurative one (that brought her national and international fame) to a philosophical thirst and a continuous search for the meaning of being human. Her public sculpture, Art takes us by the hand (2003), is probably the most notable message that Maria Lai left behind. On a large chalkboard like surface Lai has inscribed in child-like cursive, l’arte ci prende per mano (art takes us by the hand); it is a clear invitation to allow art to guide each one of us to understand the world. For Lai, art was a catalyst for encounters, an excellent pretext for learning about life and discovering the meaning of it. From the first Telai (Looms) to Tele cucite (Sewn canvases) and from Libri cuciti (Sewn books) to Geografie (Geographies), to the very last performative pieces, playfulness and imagination play a central part in the artist’s process.

Even if the game of art began during her youngest years in the Sardinian countryside, the turning point was in 1939 when she attended the Artistic High School in Rome. “For me, enrolling in Rome meant moving away from a patriarchal culture that made women prisoners. I was aware that the path of art was also the path of my emancipation,” she wrote in many interviews. Once she had finished her high school studies, while the war was beginning its first moments of terror, she didn’t return home but travelled north, first to Verona and after a short time to Venice, in 1943, where she enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts. Here, she met influential artistic personalities who profoundly marked her path, such as Arturo Martini. Her inclination for experimentation led her never to settle for one style, as many other artists did, but rather to push the boundaries further and further, not only using new materials but also different symbols and signs. When the war ended, she returned to the island where a period of reflection began, as if her spirit and thirst for art were not yet ready for Sardinia.

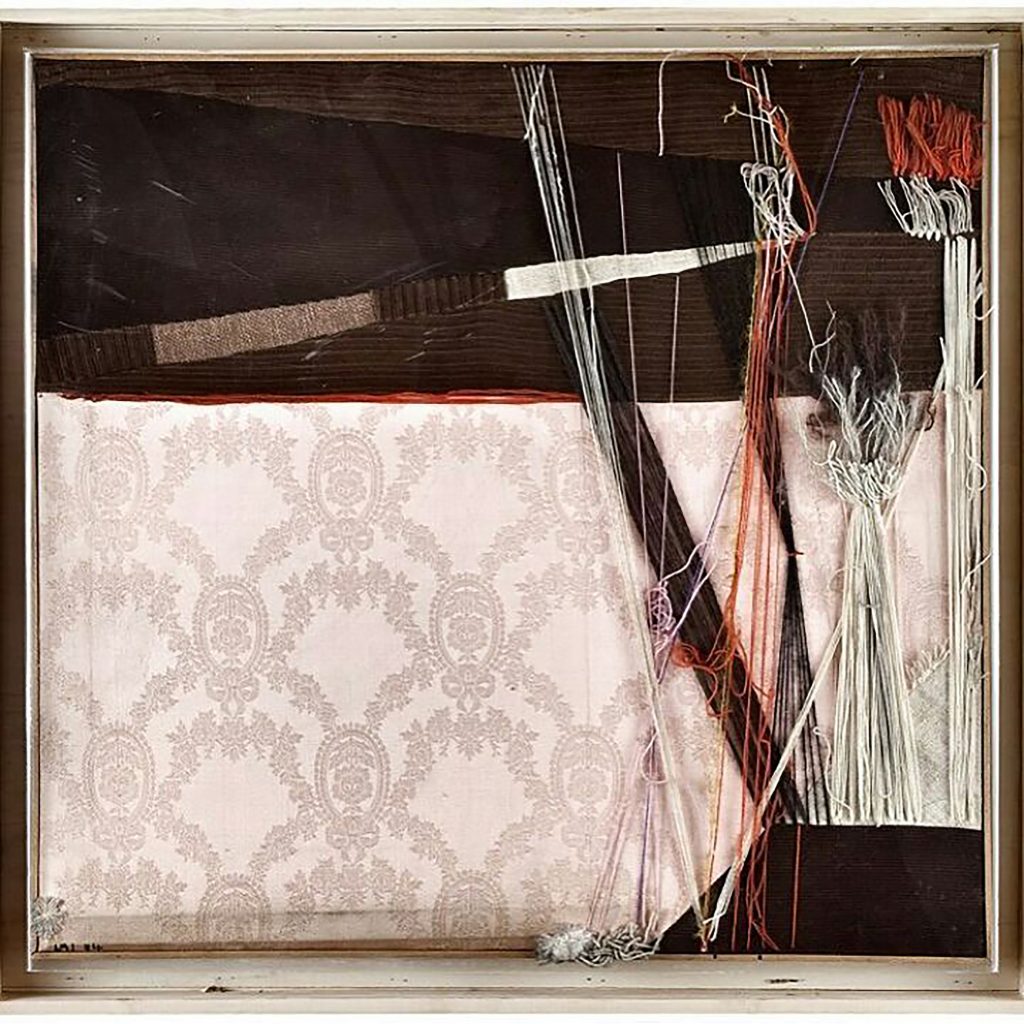

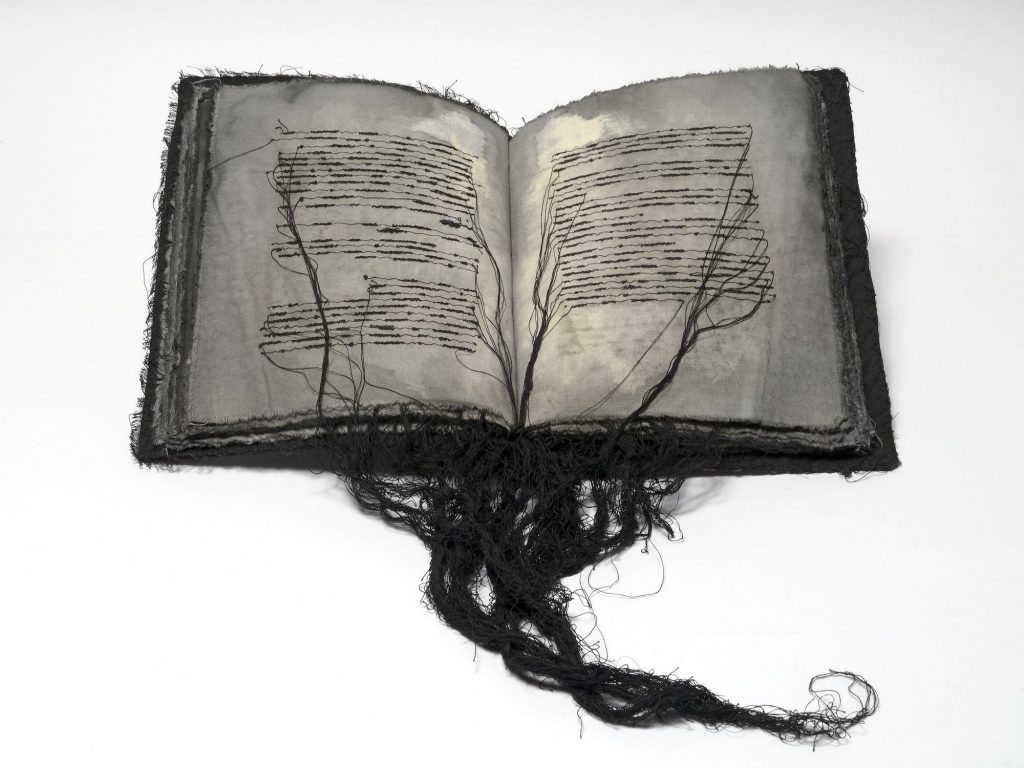

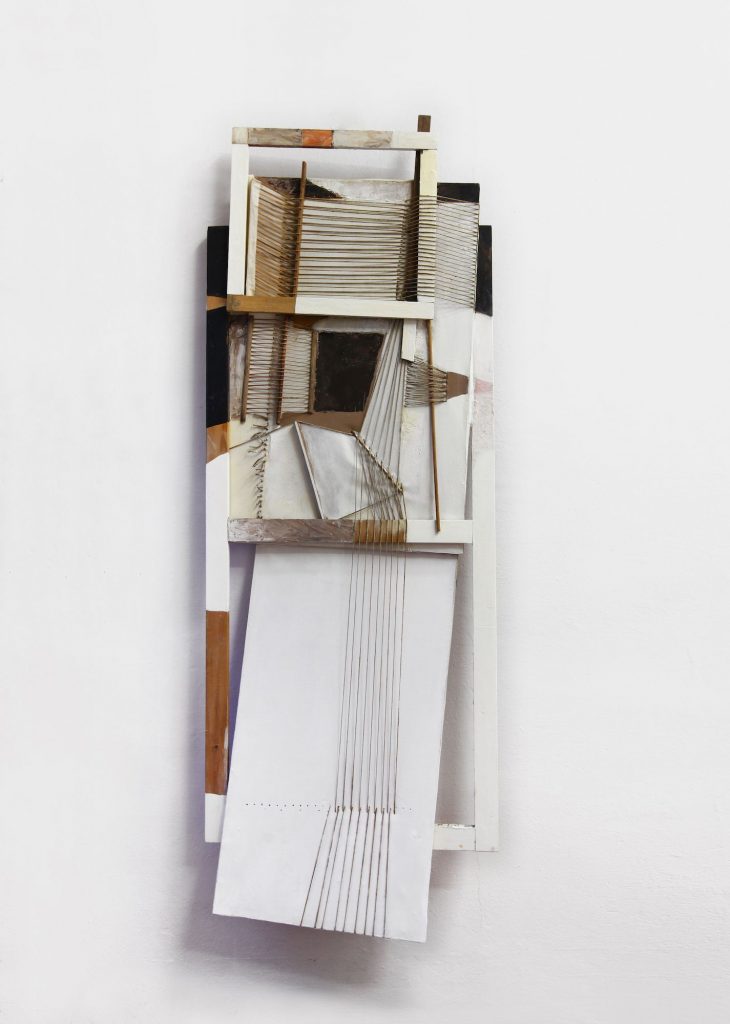

When she returned to Rome at the end of the 1950s, the fruits of her time in Sardinia began to emerge with the first Telai series, soon to be joined by Libri Cuciti and Geografie. “The astral maps responded to the need for a relationship with the infinite. Stitched books, on the contrary, ask to be held in the hands, touched, leafed through page by page, more attentively”, she said in her biography. If the Telai result from that introspective time, Libri Cuciti are its silent guardians, intimate treasure cases of legends, fairy tales and stories composed of fabrics, canvases, pieces of jeans and transparent film. “Using myths and legends,” says her niece, “was expedient to get as many people as possible to understand art and, above all, the importance of art in human growth. The use of fairy tales worked to capture attention, tell mysteries and desires that cannot be expressed otherwise. Sardinian fairy tales are little known in the world and so were the right vessel to create a dialogue about art so that people would ask themselves what art is and why we should approach art.” Geografie is a series of exceptional works in which the thread becomes the trace of visionary map-making and imaginative routes; they are invitations to travel and an expression of the artist’s need to reconnect to a boundless universe.

Towards the end of the 1970s, Maria Lai took a further step in her artistic practice, creating outdoor installations that offered her a new platform to play with scale and dimension. An early example is La casa cucita (The Stitched House) made in Selargius, Sardinia in 1979. A few years later, when asked to create a war memorial for the small village of Ulassai, Maria Lai went a step further, proposing a public art action similar to performance art. “A work for the living, not for the dead,” was her answer, and after a year spent in dialogue with the townspeople, Legarsi alla montagna came to life – a potent yet straightforward action that included the entire community. On 8th September 1981, Maria Lai connected the village to the mountain above with a ribbon made of jean material, blue like the one that saved a little girl from the collapse of a cave in an ancient legend. The yarn, a constant throughout the artist’s work, on this occasion became a 26-kilometre-long ribbon, and what had always been her individual artistic gesture here became a collective gesture. Legarsi alla montagna remains an emblematic work for its both its scale and ambition and her ability to successfully bring in nature, looms, fairy tales, books, legends and people. After this experience, her art was ready to explode with urban and environmental interventions, inside and outside her island. La strada del rito (The ritual road) and Le capre cucite (Stitched goats), made in Ulassai in 1992, are other significant examples.

“Art was a game for her, but a very serious game, full of meanings and educational messages,” says her niece today, adding: “as in her Gioco delle carte, in which the instruction booklet was nothing more than a pretext to provoke questions, to make the mind grow, to add threads to a larger design.” Pleasantly ambitious, extremely intelligent and severe with others and herself, Maria Lai has always strived for completeness in art, which can only be achieved through endless practice and great sincerity. Looking at her body of work today, the red thread that flows through it is the exquisite grace with which she managed to make each work present in its time and equally a harbinger of messages for the years to come.