Maastricht: The Materiality of the Invisible

This autumn, three Maastricht institutions mount a joint exhibition, exploring the potential of artistic interpretation as a viable means of digging up archaeological truth. TLmag spoke to Van Eyck artistic programme director and co-curator Huib Haye van der Werf about the transcendent showcase.

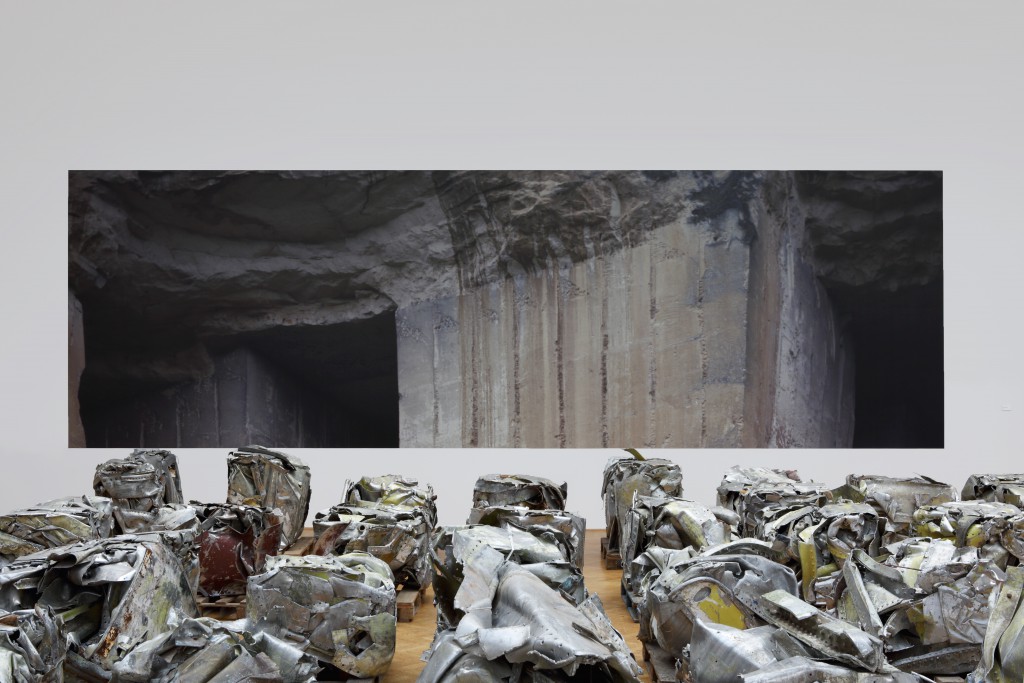

Revealing how artistic interpretation can articulate the reevaluated qualities of archeological praxis that are emerging today, The Materiality of the Invisible exhibition (on view till 26 November) spreads across three varied yet aligned Maastricht institutions: the Jan van Eyck Academie, Marres: Huis voor Hedendaagse Cultuur (House of Contemporary Culture), and Bureau Europa. Coinciding with the European Association of Archeologists (EAA) annual conference – this past September – the citywide showcase presents the work of 35 artists. Each addresses the fluid definition of archeological investigation from different vantage points and expressive mediums. The various works on view draw from the past and present to peal back underlying layers of contemporary cultural, social, and political relevance. No less evident is rich materiality and tactile forms. Working within the frame of the ongoing European project NEARCH (New scenarios for a community involved archaeology), curators Lex ter Braak, Huib Haye van der Werf (Van Eyck), Valentijn Byvanck (Marres), and Saskia van Stein (Bureau Europa) developed the multi-venue exhibition around six collaborative projects, developed by talents working with archaeological initiatives and academic departments. TLmag spoke to van der Werf about the exhibition and ongoing project.

TLmag: From where did the idea for this exhibition derive?

Huib Haye van der Werf: It was initiated by the different partners who joined the NEARCH project, including those focusing on artistic practice: Le Centquatre-Paris and us, the Jan van Eyck Academie in Maastricht. With our Parisian counterpart, we offered our very specific expertise to question some of the circumstances that archaeology – as an investigative discipline – is wrestling with at the moment. We explored how interpretation can uncover information and how such results can become valuable and presentable knowledge.

TLmag: Talk about the importance of communication and dissemination. What audience does this project and subsequent exhibition target?

H.H.v.d.W: The question of how a wider audience might understand this material is important. For the exhibition, we published a guide that allows the general public to navigate the different projects on view at the three venues. However the initiative was originally developed for the archeologist community; having reached a point where they were willing to explore the potential of external input and dialogue with other disciplines like the arts.

TLmag: How were the archaeological institutions involved able to surmount the challenges that come with interdisciplinary discourse; in other words, allowing artists to enter their ranks? What was the nature of these collaborations?

H.H.v.d.W: We put out a call for artistic practices willing to work with archeological institutions and faculties, more than and just individual experts. From about 350 applicants, we chose 6 talents. One example was Columbian artist Leyla Cárdenas, who worked with York University. She found that operating within the archaeological context, informed a new direction in her approach more than it reflected back on the field itself. Her work is on view at Bureau Europa.

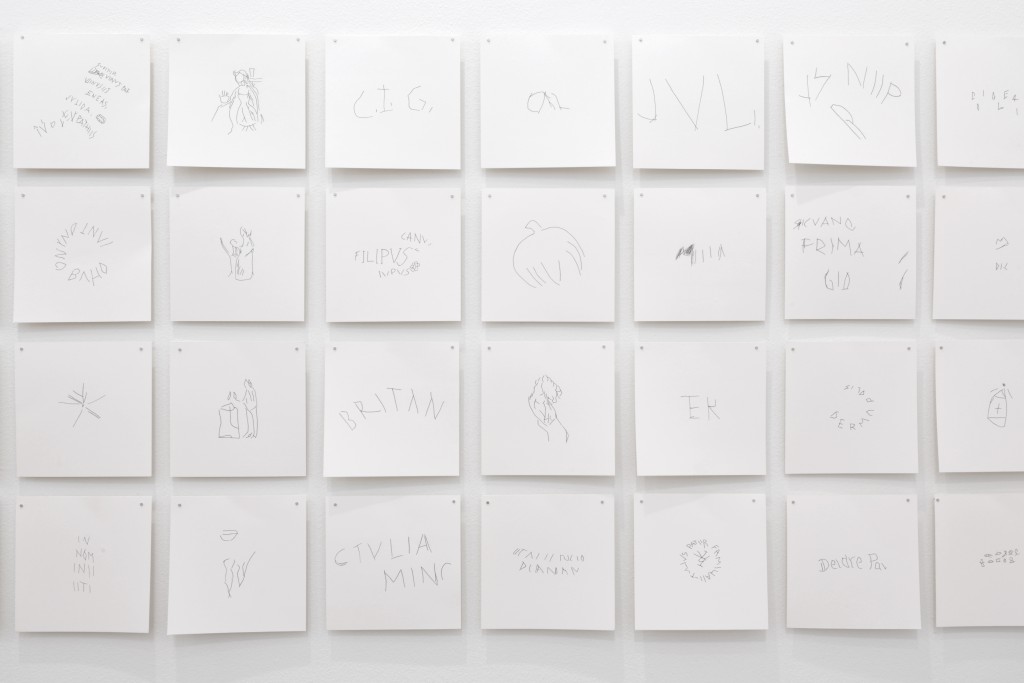

The quality of mutually beneficial cross-pollination was much more evident in the work of the Basque and Dutch talents Iratxe Jaio and Klaas van Gorkum, collaborating with Spanish platform Insipid. The duo’s work was actually quite crucial in establishing a new archeological discovery; one that has political implications. The archeologists they worked with were actually quite keen to present these findings within an artistic guise; providing them with an explicit format to deal with that tension. From a dig-site in the Spanish Basque Country, Jaio and van Gorkum explored the recent discovery of ceramic shards that featured different types of script. The scientific conclusion that came out of one of these examples challenged the Spanish government’s definition of when Basque language began. The issue was surfaced thanks to the autonomy assumed by the artists. The archaeologists suddenly had a new voice. However, they were quickly fired after presenting their conclusion. Their replacements sought to alter the facts in favour of government directives. They determined that the first result was a forgery and in turn a criminal act. The project is a series of 200 relief drawings taken from the clay shards in question called Sticks and Stone. The second part of the project is a video documenting the dig and featuring an interview with the first archaeologists about their contentions with Madrid. Both are on view at the Van Eyck. Due to its charged association, we had to be very careful in how we exhibited this work.

When considering where the constructive tension between art and archeology lie in the overall exhibition project, it’s important to think about the conditions of truth. It’s not an artist’s obligation to adhere to this quality but to interpret the knowledge and resources that they come by. In that same way, the audience should also be free to come to their own conclusions without too much predetermined steerage from the artist or curator. The deeper archeological question that arose early on in this project was how we could affirm truth through the inferences the artists would make about the larger sociological or economical implication of historical objects.

TLmag: Because the works are blatant interpretations, they are perhaps more accessible; allowing visitors to draw their own conclusions. If looking at the history of antiquarianism, the way in which objects have been displaced from their original context into isolated museological contexts, the notion of truth can then also be altered. Returning to your point about presentation, how did these factors influence your curatorial vision?

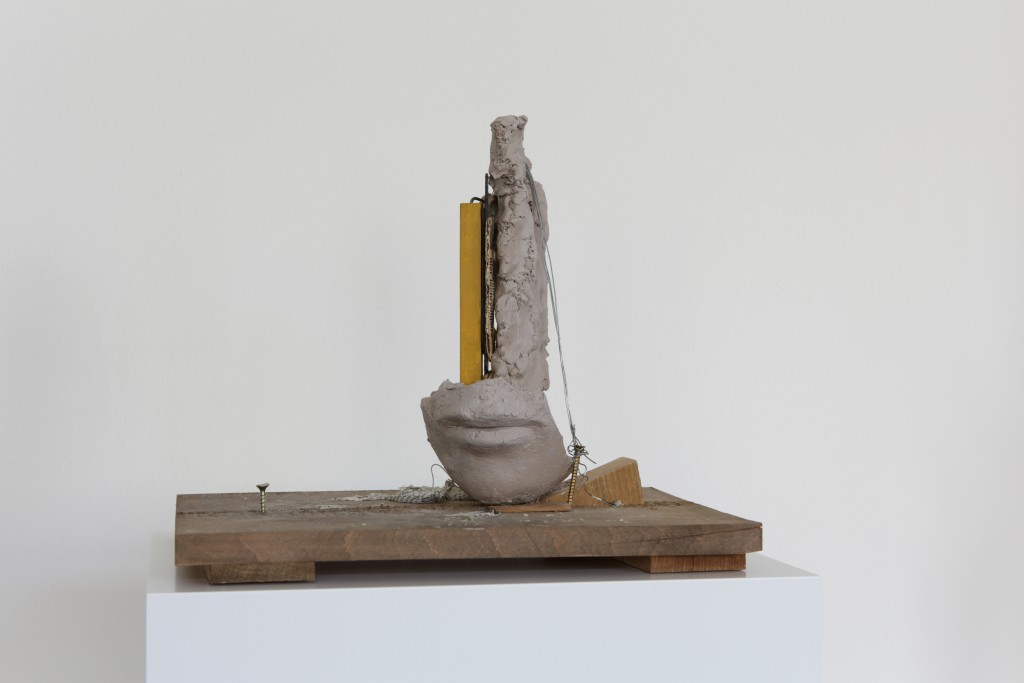

H.H.v.d.W: We had the luxury to display the results of different collaborative projects that allready explored these fundamental questions. All of the core artists made very informed and layered works. Around that, we decided to exhibit speculative and prototypical research-led works by other talents to then reinforce and ground the potency of what the six main projects express. A work by Daniel Knorr investigates the fact that before the Berlin Wall fell, the East German secret police attempted to burn and bury important documents. What the artist uncovered – based on that preliminary knowledge – were, essentially, petrified stones. Viscerally and metaphorically, one wants to take the stones and try to unfold them; to unearth the hidden information they contain. This piece is a good example of how the exhibition is both concerned with research and materiality.

TLmag: What do each of the three exhibiting institutions add to the equation?

H.H.v.d.W: Within the guide that we published for the overall exhibition, we don’t stipulate different house styles or sensibilities. Still, you can sense a difference. We kept that in mind. In general terms, describing the distribution of works in this exhibition, I would categorise the Van Eyck as driven by poetry. Marres, I would argue, also contains a poetic tinge but the works on show are more explicitly conceptual, in an avant-garde tradition. At Bureau Europa, the projects on view are more tactile. With our shared mandate for The Materiality of the Invisible exhibition, we all look to confront archeology by suggesting that there needs to be more room for interpretation.

The Materiality of the Invisible: till 26 November

Maastricht, the Netherlands:

– Jan Van Eyck Academie: Academieplein 1,

– Marres, Huis voor Hedendaagse Cultuur: Capucijnenstraat 98

– Burreau Europa: Boschstraat 9