Senyi Awa Camara: The Spirit of Creation

Tracy Lynn Chemaly writes about the animistic and powerful ceramic sculptures of Senyi Awa Camara, whose work has crossed from her rural African village into the white walls of contemporary art galleries and museums in unexpected ways.

There is a legend living in Senegal. A legend born of a legend…

It starts in a past decade (the exact date remains unclear; some say it was the year 1939, others relate the tale to 1945), in the West African village of Diouwent, where a potter bore triplets. The myth that unfolds in the Diola community to which she belonged recounts how forest spirits abducted the three children, taking them deep into their foliage to keep them safe from harm. The villagers had interpreted the multiple births as an ominous sign, a disruption to the natural order of things, and were planning to reject at least one of the offspring.

There are no precise details about why the children returned to their home, but all accounts concur that they arrived back as exceptionally skilled potters. The spirits had guided the triplets in the art of creation, an intervention that saved their lives.

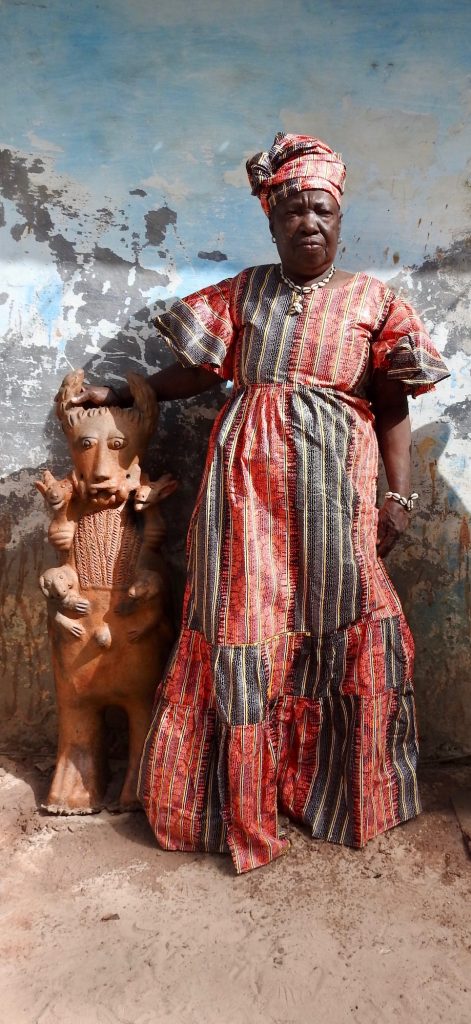

One of the triplets is Senyi Awa Camara, an artist who to this day transforms clay into totemic sculptures that appear to be informed by those same guiding spirits in one way or another. People who choose not to believe the tale of the forest spirits say that the potter was taught by her mother. Regardless, in the more than 75 years since her birth, Camara has progressed from making traditional utilitarian pottery and small sculptures which she sold at the market, to developing up to three-metre-tall mystical-looking animist forms. The latter have been shown in some of the art world’s most prestigious institutions – from the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao to the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris – and reside in the homes of global collectors bewitched by these curious artforms.

The success of Camara’s work is far removed from her humble lifestyle. She works from home, a tin-roof structure in the Senegalese town of Bignona, firing her terracotta pieces in an open-hearth kiln in her garden, tirelessly producing mammoth creations despite her age.

It was perhaps the time Camara spent with her first husband that most influenced the themes of her work. She was married while still a teenager, and suffered at least four traumatic miscarriages before her husband left her.

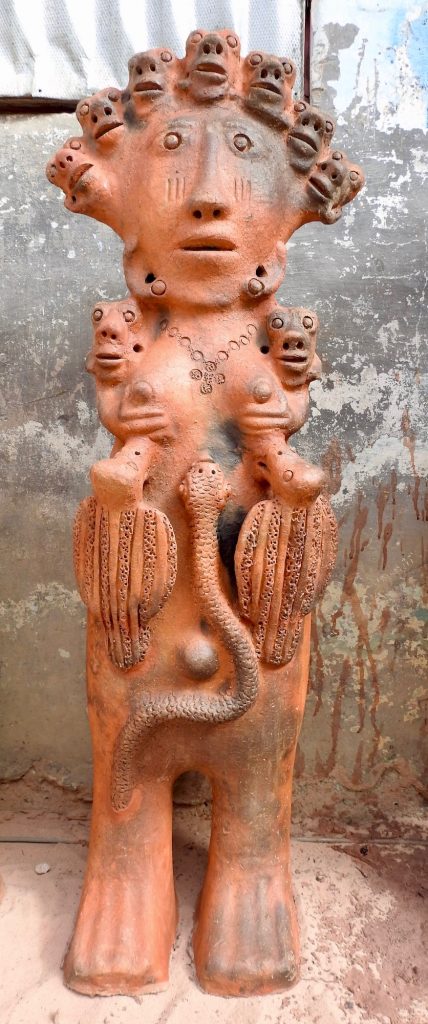

Her multi-limbed, many-breasted creatures, pregnant human bodies, clinging infants and undefinable animal-like forms depict these and other poignant moments in her life. By mythologizing her own history through these animist sculptures, the artist has found a way to capture universal tales of procreation and motherhood that strike a chord regardless of one’s heritage or spiritual inclination. Hers is a body of work connected to the human capacity to endure suffering, fear and loss, captured through clay, the elemental material that itself is bashed, prodded and manipulated.

Camara’s second husband, Samba Diallo, is credited for encouraging her to be a professional artist, and to embrace her talent despite ‘art’ being an unusual concept in her community. When he died in 2004, his wife’s work had already gained the international recognition he knew it deserved, showing at the Venice Biennale in 2001. That was 12 years after Camara’s sculptures were first seen outside of Senegal, in a group show at the Centre Pompidou in 1989, curated by Jean-Hubert Martin. In the exhibition, titled ‘Magicians of the Earth’, Camara’s work was noted for its spiritual, mystical and authentic qualities. Even when displayed far from the earth from which it is created – far removed from forest spirits and fires of creation – there seems to be a palpable energy felt in Camara’s sculptures.

Speaking only her village dialect of Diola, Camara does not participate in interviews. The closest one comes to meeting her is through Senegalese director Fatou Kandé Senghor’s 2015 documentary, Giving Birth. In it, Camara is depicted as shy yet eccentric, wearing colourful accessories and expressing a love of kung-fu films. It is through one of her apprentices that we come to understand her unique artform. Despite working daily alongside the master, the young apprentice is unable to learn from Camara. In his hands, the same pottery crumbles. Camara’s skill is too deeply ingrained to be taught, he says. “It’s a gift.” A gift that Camara still believes comes from the spirits.

Before commencing with a work of art, she makes sacrifices to these spirits, asking for the piece’s subject to appear in a dream. It usually does. When it happens, Camara locks herself in her studio and gets to work, forming the shapes that emerge from her mind.

The stories of The Potter of Casamance, as Camara is known in her region, will be relayed for generations to come, through legend and oral village tales, and through mythical clay creatures embedded with the spirit of creation.

www.baronian.eu

@baronian.gallery