Static by Glenn Adamson

Friedman Benda gallery hosts celebrated curator Glenn Adamson. The Static exhibition explores how the turbulence of the 1980s impacted design and how that might make sense again today.

The timely relevance of one’s work can either be a welcomed surprise or the fruition of a nightmare. Foremost curator and theorist Glenn Adamson mounts Static at New York’s Friedman Benda gallery on the eve of the US presidential inauguration. Though not initially meant as political commentary, the exhibition explores a time when designers grappled with “a common feeling of rupture and disorientation;” not far flung from the current climate. Adamson brings together an eclectic range of works from different applications, movements, countries and decades. In doing so, he paints a full picture that draws us back into the Postmodern zeitgeist.

The 1980s were creatively chaotic. The decade was defined by various extremes: growth and decline, wealth and disparity, individualism and conformity. By titling his exhibition Static, the curator suggests that the era was marked by a sense of stagnation; a period lost in conflicting historical, cultural, and visual associations. Whereas today such a reality might allude to digital noise, pixelation or glitches, the 1980s revealed a plethora of stylistic attributions;pieced-together from new material values and assessed qualities.

The previous decades of the 1960s and 1970s saw the rise of conceptual and speculative design. No longer subject to the ‘form follows function’ dogma or the constraint of mass production, designers could operate like artists and use their medium to express meaning or message. However muddled by rampant commercialism and pure self-expression, such critical and political engagement remained prevalent throughout the 1980s.

In this spirit, Static is presented as a carefully arranged display of statement pieces. Alessandro Mendini’s Lassu sculpture (a chair mounted on a staircase and covered in an implosive array of coloured tape) is strategically juxtaposed with Ettore Sottsass’ Ventrinetta di Famiglia (a cabinet demonstrating the designer’s preference for consumer-grade materials like terrazzo laminate and in this case, coloured fluorescents.) Adamson explains that within the scope of Italian design, Mendini’s nihilism was like a setting sun while Sottsass’s exuberance was like a rising sun. It was Sottsass’ cabinet that inspired Adamson to choose his title. The graphic pattern of the laminate is similar to T.V. static. However, this poetic interpretation does not overpower his curatorial vision. Rather, it provides a perfect entry into understanding the playful and satirical nature of the works on show.

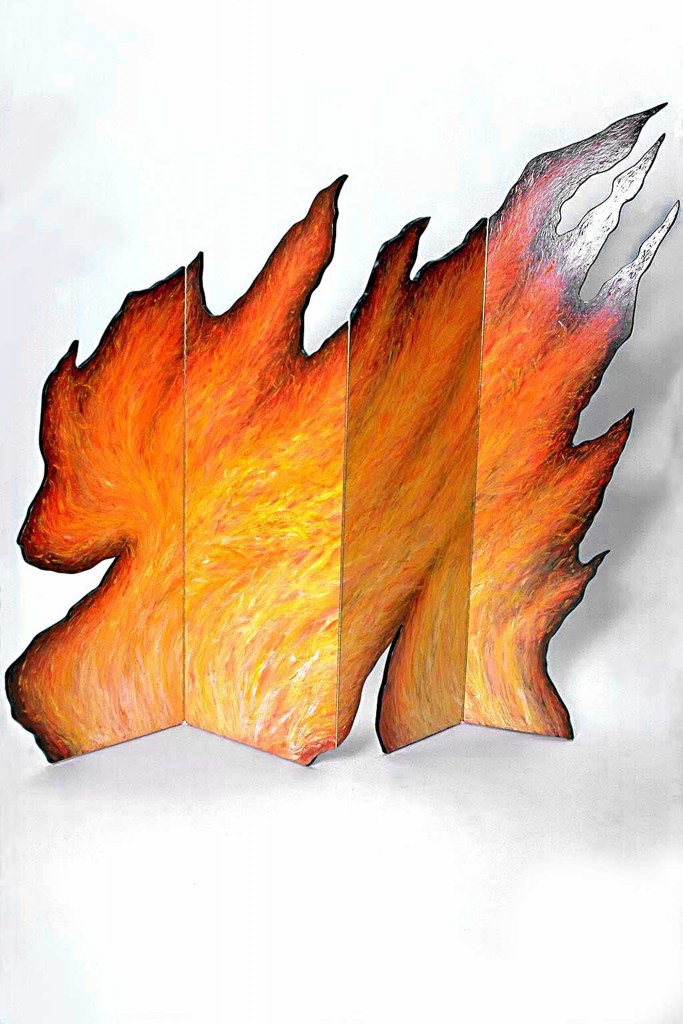

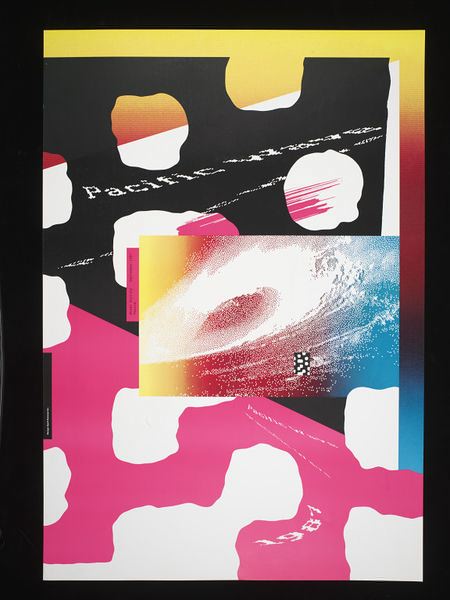

Adamson also puts a strong emphasis on the work of Gaetano Pesce; New York’s city’s adoptive son. As one of the forefathers of Italian Radical Design, Pesce’s oeuvre demonstrates how Postmodernist employed historical and cultural references in their work. Expanding its geographic range, Static also presents works byWolfgang Lauberscheimer of the German Pentagon movement. Other lesser known names include British legend Danny Lane, American talent Howard Meister and Californian graphic design innovator April Greiman. By mounting a dynamic historical survey, Adamson asks us to consider how we might foreshadow the near future? Will creatives fall victim to growing extremes, limitations, and stylistic perplexity or – like in 1970s and 1980s New York City – thrive under pressure?

Static – till 11 February

Friedman Benda

515 W 26th St.

New York, NY, US

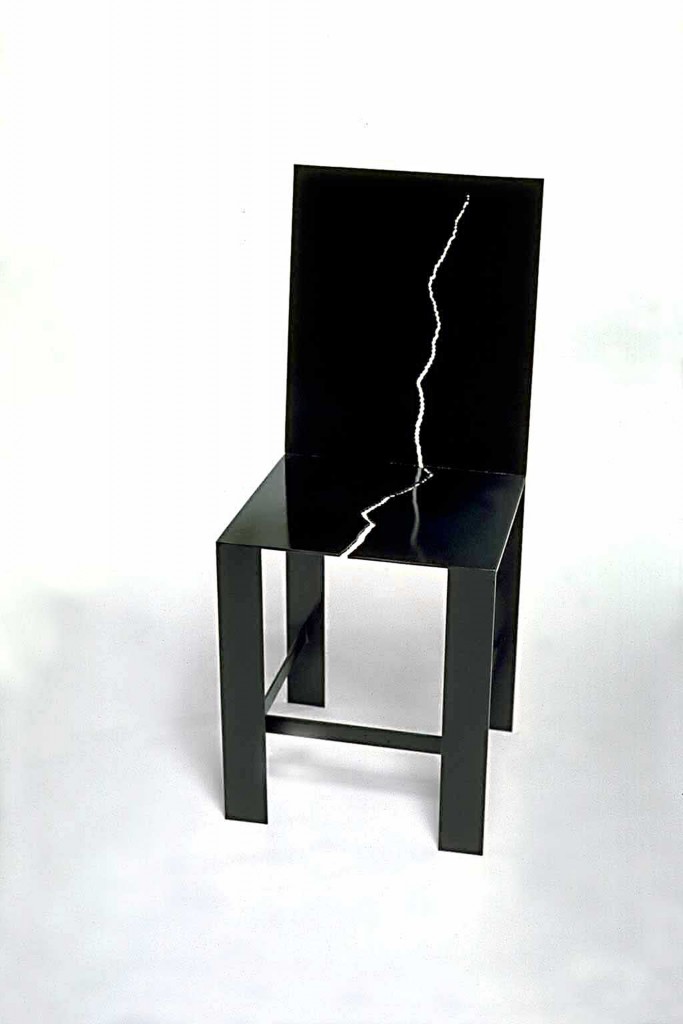

Pratt Chair by Gaetano Pesce (1984)

Cone Table by Ron Arad (1986)