Tasting the Faroe Islands: KOKS

The young chef, Poul Andrias Ziska, distils the flavours of the Faroese Islands into a much-praised, experimental restaurant.

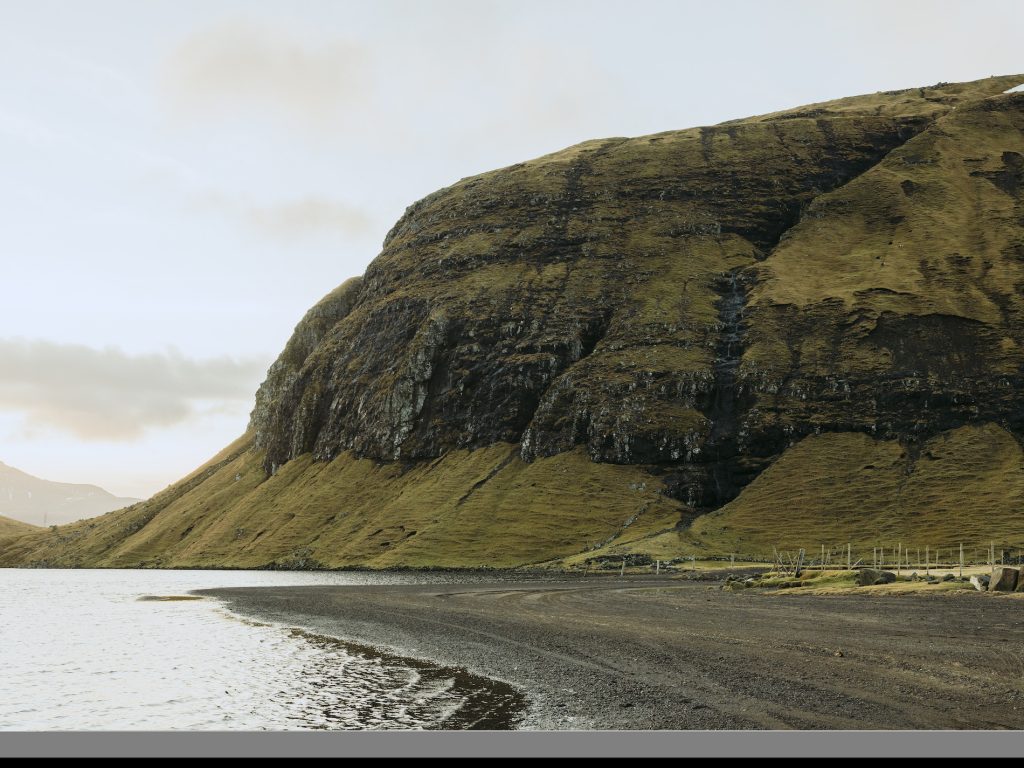

So remote is KOKS, in the Faroe Islands, that diners can’t drive there. At the restaurant’s fermenting house, clients leave their vehicles. “There’s a river to drive through so it’s better we pick people up,” explains Poul Andrias Ziska, chef and proprietor of the 26-seat restaurant, which is housed in a turf-roofed farmhouse alone above a lake. Against this backdrop, Ziska, who grew up in nearby Tórshavn on Streymoy Island, shows an unwavering commitment to sustainable and indigenous produce. Two hundred miles north of Scotland and only 540 miles3, it would be easy to assume the Faroese culinary repertoire is limiting for a Michelin-starred chef like Ziska. Yet with waters stretching thousands of miles and a vast coastline, these 18 islands, where no trees grow, are surprisingly abundant and rich in natural resources. “Come September, about 95% of the ingredients are from the land and sea here,” says Ziska, with pride.

“There’s a make-do “survivalist” mentality when it comes to sustenance,” he explains. “The Faroese have always preserved, people aren’t proud of it, it’s from necessity to make food last longer,” he says, defining life here. Almost every inhabitant has a shed, for example, where they hang joints of lamb and fish from the eaves, for days, if not months. This technique, known as raest, results in wrinkled, punchy-flavoured putrefied meats. Whereas in restaurants further south in Europe, the comestibles would be cured before air-drying, here the salty Atlantic sea winds are left to effortlessly preserve.

Ziska’s ambition is to trophy such atavistic methods and ingredients throughout his 17-course tasting menu. What’s unique is his experimentation. At KOKS, you might find months-aged fermented lamb tricked out with crisp reindeer lichen, a local mushroom emulsion and pickled berries. Diners are invited to sprinkle over carefully-dried seaweeds with umami nuances. Considering the refined menu, it would be reasonable to assume a chef, who predominantly serves visitors from abroad, might shy away from plating up seabirds like fulmar and gannet, a staple among the islands’ inhabitants. But KOKS menu is both creative and uncompromising, placing them centre-stage. “Traditionally, fulmar would be boiled. But I make a dish where I panfry it, serving it pink. It comes with pickled rosehip petals, elderberries, and beetroot sauce in Sichuan pepper.”

As well as looking to the past, Ziska, who has worked at legendary restaurants like Spain’s, Mugaritz, and Denmark’s, Noma, before moving home, is fascinated with exploring new flavour profiles on these shorelines. Like Rene Redzepi of Noma and other global illuminati, new gastronomic potential enthrals him. “We source a lot of flora and fauna here that local people haven’t heard about.” Today, he’s intrigued by a seaweed discovery. “People haven’t heard of this and it could grow anywhere, but we’ve found a parasite seaweed that grows on bladderwrack and tastes of truffles.”

For plant matter, the landscape is equally alluring. Adding to the regular supply of potato, turnip, kohlrabi and rhubarb (root veg thrive on the islands because they can shelter beneath the soil), freshly foraged botanicals –– arctic-alpine plants, wildflowers, grasses, moss and lichen – are utilised at KOKS. Over a thousand years, dating as far back as the Viking settlers of the ninth and tenth century, it’s clear every mountain and meadow on these rugged islands have been unturned and scoured for food. What remains so bewitching is these harsh hinterlands appear resiliently untouched.

This piece is republished from TLmag’s Spring/Summer 2019 edition, TLmag31: Islands of Creation.

@ koks_restaurant