The Archaeology of Colour

For TLmag38: Origins, Laura Daza Carreno wrote about the archaeology of colour and applying the study of ancient colourants and the knowledge of traditional colour making to better understand human evolution.

Some researchers argue that craft has existed from the moment humans started using tools, such as stones or utensils, because any use of tools involves the act of skilled making. Since prehistoric times, the connection between hand, brain and material has led to the development of human intelligence. Therefore, colour-craft has been crucial for the evolution of humanity.

We take it for granted that colour was once hand crafted in a detailed manner; that it had a unique story and magic behind it. Used to enhance humanity in different ways, through ornamentation, dyed on textiles, painted onto the bodies as ritual or permanently tattooed. Over the centuries, colour has been defined in many ways – as light, as a physical material, as a sensation. It can be said that each culture defined colour according to its history, environment, traditions and wisdom. It was an integral element across cultures, denoting meaning and social status – it was a desirable element in everyday life. For example, red, carries an important meaning in most of civilisations. Associated with the element of fire, blood, fertility and life force; early cultures used to extract this hue from iron oxides (hematite); minerals (cinnabar) and insects (cochineal and kermes).

Mineral pigments have been used for manufacturing colour for thousands of years. Many prehistoric and ancient pigments were humble and ordinary, with a glorious history in the world of art and pigment making – producing brilliant hues. Sources such as earths, clays, shells, charcoal and soot were easy to find, whereas other sources for colour were very sought after. Red ochre is a coloured earth considered to be the first pigment used by the oldest of civilisations (dating from around 350,000 BC.) Sinopia, (named after the city Sinop in Turkey), is one of the most important red earth pigments and widely used by Renaissance painters to outline their artworks before painting them.

Another example of natural earths is Burnt sienna, (terra di siena, in Italian), a yellow ochre known as raw sienna, and originally found in Tuscany. The rusted shade was obtained by a thermal processing of the material (raw sienna), which allows the colour to change. This phenomenon of colour transition has been known since the Palaeolithic Era, which not only makes it the first synthetic pigment but also the earliest form of pyro-technology.

Throughout history, alchemists, artists and chemists such as Cennino Cennini, Pliny the Elder and Vitruvius, have documented in traditional manuscripts, different alchemical processes, concoction recipes and methods for crafting pigments and dyes. Alchemy was a discipline that combined early science, craft and technology and through trial and error, led to breakthrough innovations in colour and colour-making.

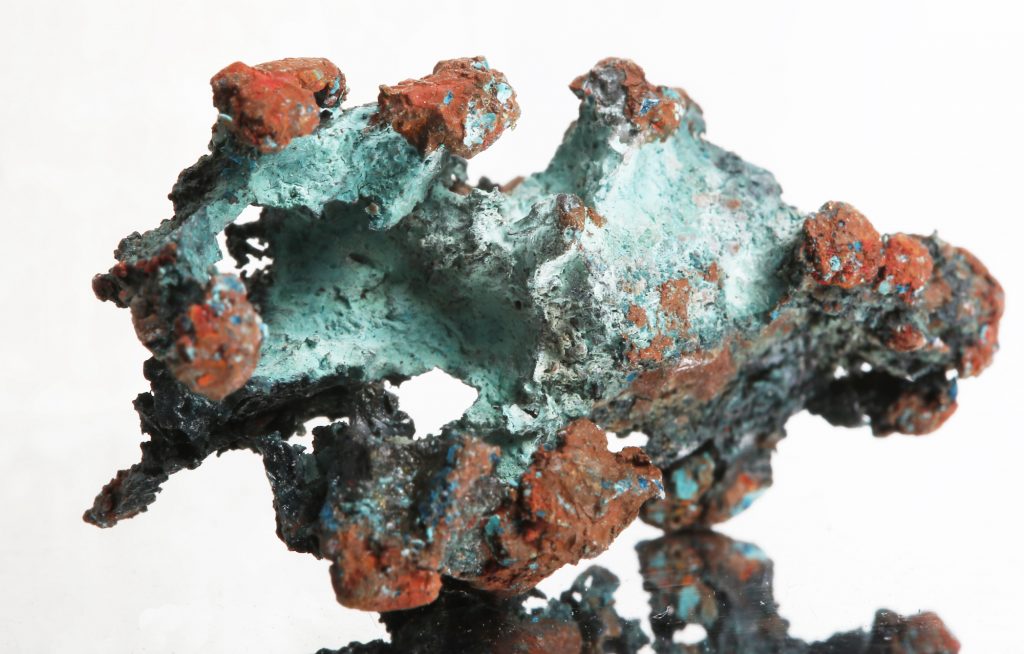

While the notion that Egyptians were masters in the art of fire – inventing alchemy, colour craft and glass manufacturing, some researchers assert that since Antiquity, Egyptian alchemists had known how to turn copper into Verdigris or lead sheets into a white powder known as Lead white. Verdigris is a man-made turquoise pigment that was manufactured using different recipes. The simplest one was through acetic acid applied onto copper sheets that were sealed in a container; the turquoise particles that arose were scraped off and collected by hand. This pigment was widely used by European artists for decorating Illuminated manuscripts and traditional maps.

It may seem difficult to grasp other sources for colour from the animal, plant and mineral world and imagine how they obtained those glorious hues. Bizarre as it may seem, alchemists extracted pigments from sea snails, shells, urine, blood, plants, resins, toxic minerals and metals. But let’s push the boundaries even further. A particular brown shade was extracted from Egyptian mummies – human and animal parts were ground up and mixed with myrrh and pitch. Mummy brown, Egyptian mummy or caput mortuum (which means “dead head” in Latin) was a pigment favoured and sought after by Pre-Raphaelite painters in Europe. Its source was kept secret for many years; it then disappeared entirely from art for ethical reasons, and also, because the scarcity of Egyptian mummies.

From the Medieval colour palette, a more delicate but powerful colour pigment comes from a Mediterranean spice. Saffron, crocus sativus, was used as both a dye and pigment; able to colour liquid, skin, hair and cloth with the ability to dye ten times more of its own weight. Used across many cultures for dyeing, flavouring, perfumery, medicinal purposes and painting – including to imitate gold leaf to illuminate the pages of manuscripts.

We can perhaps envision another Medieval red pigment called Dragonsblood, believed to be obtained from coagulated dragon blood, but in reality, it was a tree resin. Alchemists used peculiar names to identify their colours in order to create a sense of mystery and magic. Many of the recipes found in old manuscripts were kept secret for copyright protection so that just a few had access to them and understood the language in which they were written.

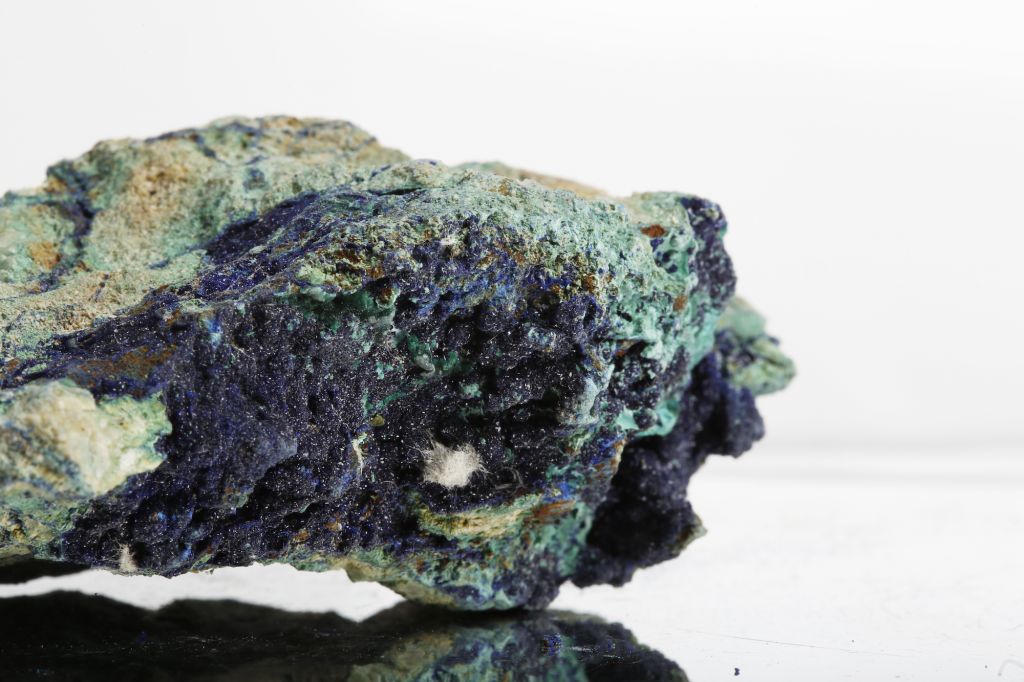

Imagine a rock or gemstone grounded, pulverized and sieved multiple times in order to obtain the finest particle size ideal to turn it into paint. Egyptians were the first ones to introduce powdered Malachite (green pigment) and Azurite (blue pigment). Both are copper carbonate minerals historically used in amulets, jewellery, cosmetics, paint and eye shadow. Some researchers affirm that these were the first green and blue colours ever used and invented by humans.

Azurite stone was less expensive to use, making it a good substitute for Lapis lazuli, a luxurious gemstone that makes ultramarine blue. A ground-up form of the mineral lapis lazuli, which was imported from Badakhshan in Afghanistan, makes ultramarine blue, the most expensive blue pigment since the Middle Ages.

On the contrary, shades and hues are manufactured today in a completely different manner. As colour historian and scientist Spike Bucklow says, “In modern times, we have divorced colour from its origins, using it for commercial advantage”, meaning artists have forgotten the ancestry, the craft of extracting and distilling vibrant hues. Ready-made paints are available today in art shops and colour is easily replicated.

But thinking about the archaeology of colour might clarify some of the arguments around the idea of the Egyptians as pioneers and masters in many ways, especially as colour alchemists. That the tracing of historical colours allows a better understanding of its provenance, as colours had a relationship with its place of origin. And that there is a wide and hidden history of colourants, dyes and pigments, still unknown to many and it is relevant to bring it into people’s awareness in order to understand our human history.

@studio.laura.daza

@lauradazacarreno