The New Establishment

Five contemporary artists helping to shape the global discourse around and market for contemporary African art.

In recent years, contemporary African artists have garnered fresh acclaim for their disruptive take on the key issues of our time. Drawing on traditional crafts, politics and elements of African and Western pop culture, these artists are defining contemporary art―proving that art from the African continent isn’t a trend, but an essential new way for us to see the world. Contemporary African creativity has now surpassed its niche status to become a mainstream movement that’s both commodifiable and fashionable. In 2013, 1-54 Contemporary Art Fair launched at Somerset House, London. Founded by Touria El Glaoui, the fair’s success was a landmark moment and it has since expanded to New York and has just launched its third location in Marrakech. In 2017, Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa launched in Cape Town―the largest non-profit art museum in Africa― and Ghana became a tourist destination by virtue of its prolific art scene, including the recently launched 1957 Gallery, ANO Centre for Cultural Research and the street art festival Chale Wote.

Today, the phrase ‘African art’ has become a common term. But of course it is no new thing. For decades, multidisciplinary African artists have been defining the contemporary art market. With it’s themes from the domestic to the political, their work has long found an enduring audience, interested in Africa as a cultural, social and business destination. “The continent of Africa has some of the most important visual traditions in the world,” says Touria El Glaoui. “There has always been an interest in African contemproary art but now that curators are considering African artists, there’s a demand for it.” 1-54’s success has been followed by likeminded fairs such as AKAA in Paris and ART X Lagos, not to mention the ongoing popularity of Cape Town Art Fair and Joburg Art Fair and regular auctions at Bonhams in London. In 2016, Bonhams saw an increase of five times the amount in African art sales over the last decade, to €50,000 profit. Here Africa is a huge continent and the art scenes within it are characterised by their location. In West Africa, particularly Ghana and Nigeria, young artists are emerging with radical practices such as performance and politics.In South Africa, native established artists have found a new international platform. At the centre of their trade is disruptive work that draws on the heritage crafts of African culture such as textiles, sculpture, performance, with 21st century themes to do with love, politics and war. Artists such as Paul Akomfrah, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, William Kentridge, Meschae Gaba, Abdoulaey Konaté and Julie Mehretu have cemented their status as international art world stars with work that riffs on the visual culture of Africa whilst referencing the western environments they live in and through. Akomfrah will be holding his first ever retrospective at The New Museum in New York this June. In the emerging arts scene, other younger artists such as Younes Baba Ali, Romuald Hazoumè, and Gocalo Mabunda draw on the traditional crafts of their hometowns and have achieved significant followings in the process. These and countless other artists have achieved both critical and market acclaim and Africa’s status as a new untapped arts destination is set to increase even further., Here e take a look at just a few of the movement’s key players, from established artists to radical new names.

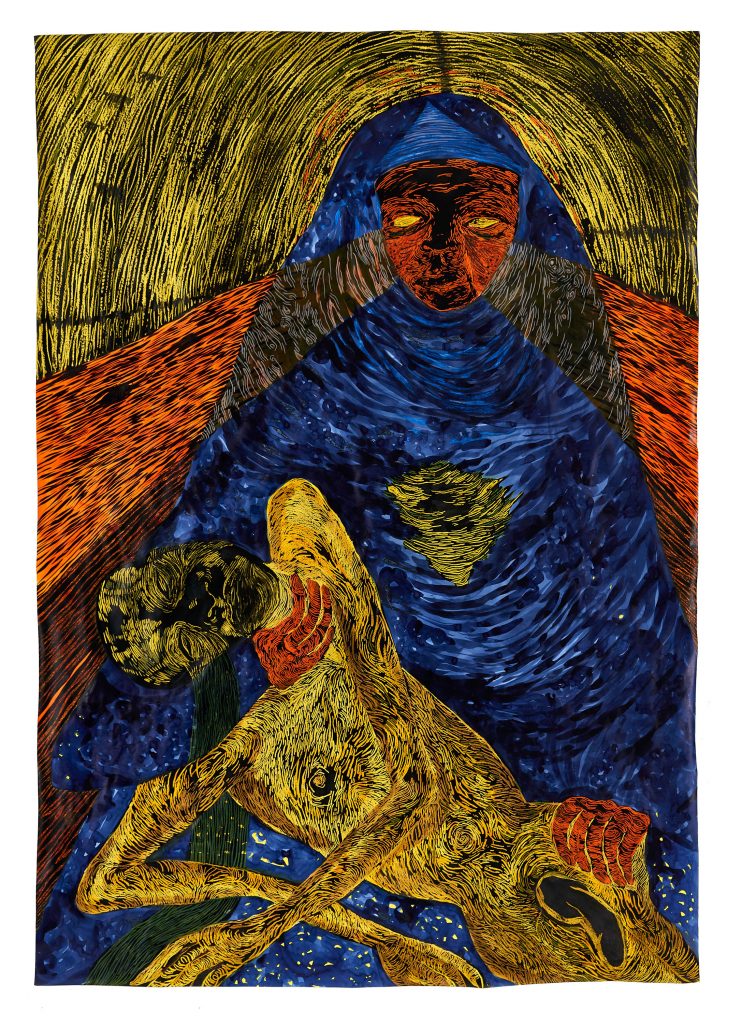

Njideka Akunyili Crosby

In Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s “Nwantinti,” 2012, a woman sits on a bed with the head of her white husband lying in her lap. The image is made out of paint, textiles and print made from photographs, typically taking three to four months to make. With it’s documentary-style take on the mundane nature of domestic life, it’s an image that epitomises the artist’s work, which spotlight’s the domestic lives of diaspora women and men, and has earned Crosby huge success. Her paintings are now on permanent display at Tate Modern, The Whitney and MoMA. Much of Crosby’s work deals with feelings of displacement, both in Nigeria and in the US. At four years old, the artist’s family moved from the small Nigerian town Crosby had been brought up in Enugu, to Lagos. She then herself moved in 1999 to study contemporary art in the United States at Swarthmore College and Yale, aged 16. Crosby’s work features elements from pop culture and current affairs in both these countries, including the 2016 painting “Ike Ya” which features a Bring Our Girls Home poster and “Mother and Child,” of the same year, which shows a picture of the artist’s own mother and herself as a baby. This modern and smart mix of contemporary Western art trends with the history of craft in Nigeria have earned the artist fans including the Obama’s.

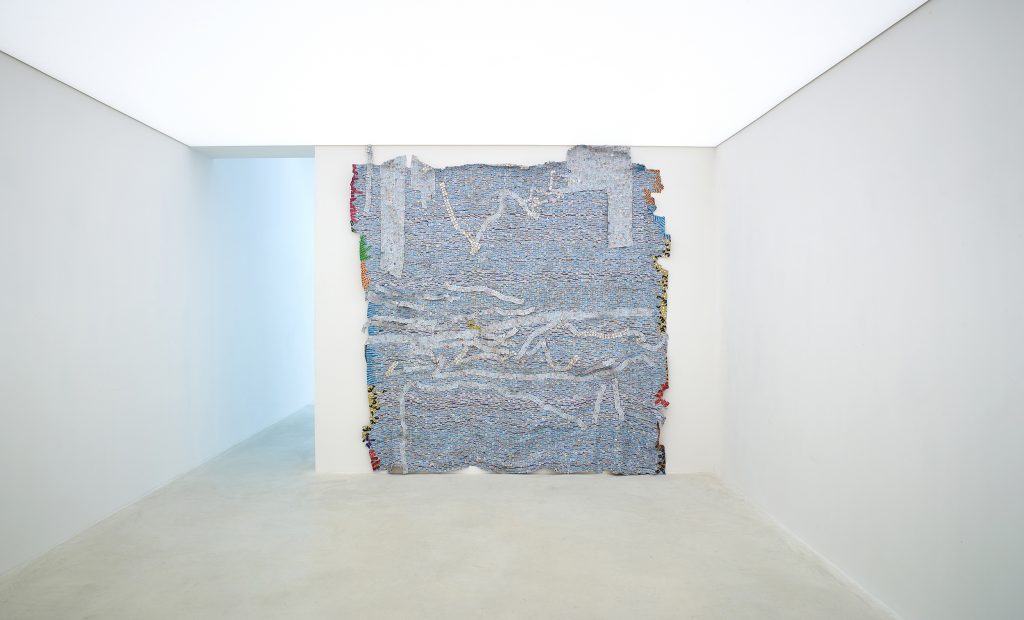

El Anatsui

Ghanaian sculptor and painter El Anatsui achieved mainstream success before there was even a market for contemporary African art, and has since blazed a trail for a new generation of young African artists. Anatsui began his career in Lagos, Nigeria, by re-purposing the petrol cans that local Nigerian communities use to transport water from wells to their homes, making them into elaborate handmade wall hangings with metal bottle caps and textiles, then stitching them all together with wire so that the works come to resemble quilts. One of his most famous iterations of this craft, “Man’s Cloth,” 2008, is in the permanent collection of the British Museum. El Anatsui was also the recipient of the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 56th Biennale di Venezia. The artist has spent the majority of his career living and working in Lagos but he travels frequently to Europe and the US to exhibit. Most recently he took temporary residency in Antwerp, Belgium, where from October 2017 to January 2018 he unveiled seven new large scale works at Axel Vervoordt Gallery in the exhibition Proximately. Using Nigerian household refuse such as plastic bags, bottles and metal, the artist used his trademark craft style to draw attention to the sustainability crisis in West Africa.

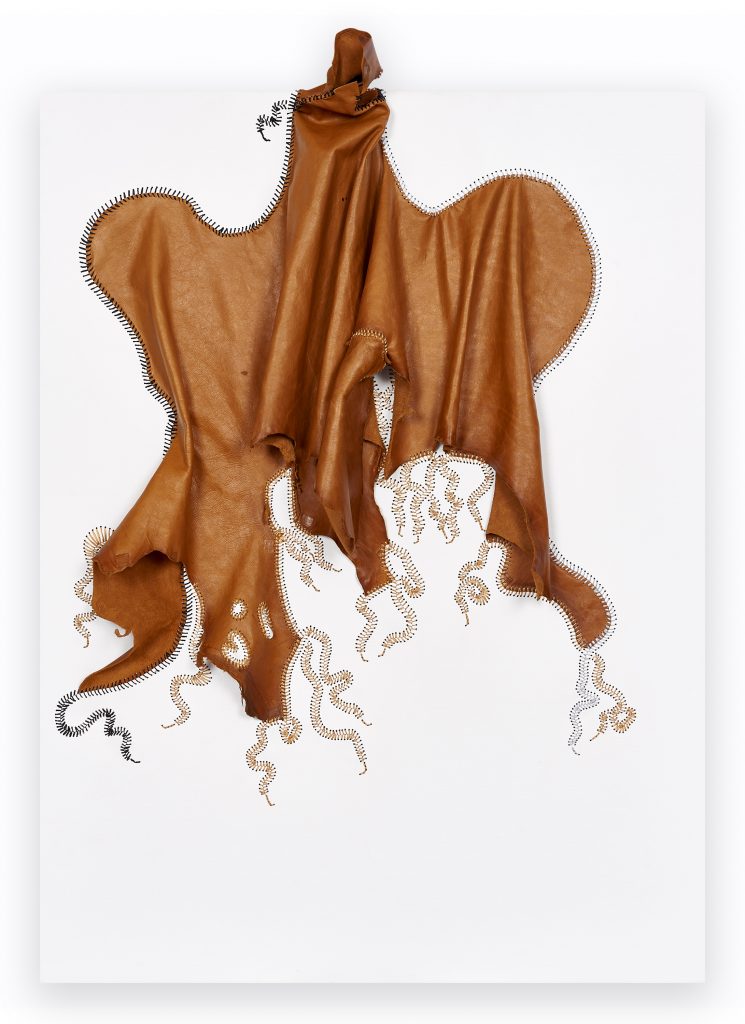

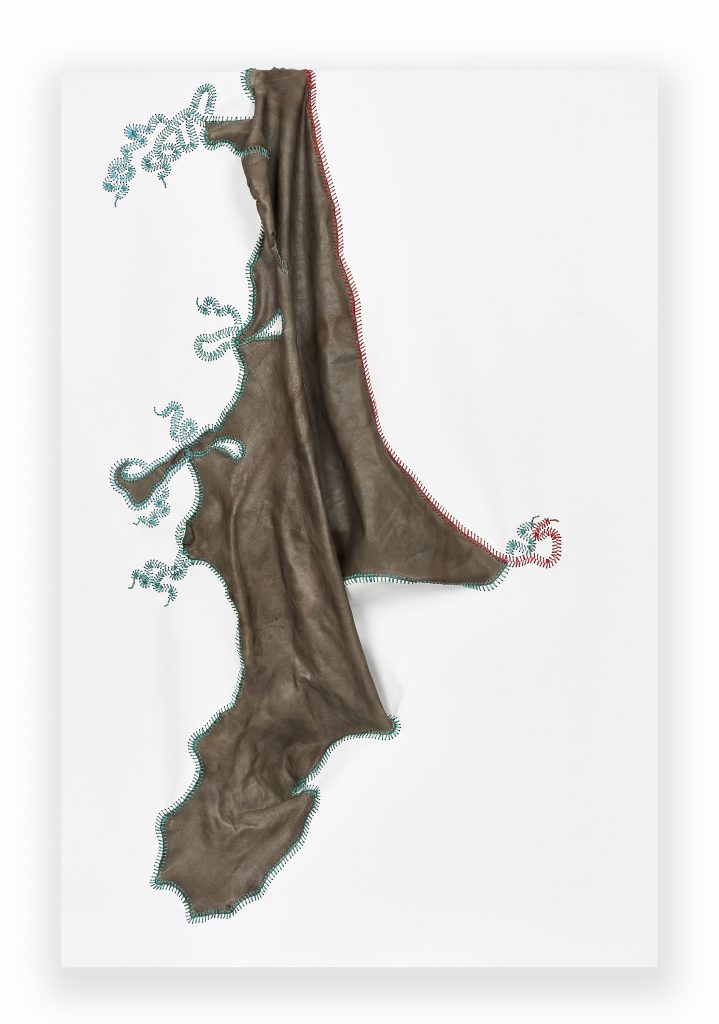

Nicholas Hlobo

Cape Town born, Johannesburg-based Nicholas Hlobo describes his work as an exploration of what it means to be a millennial South African man. His medium is predominantly in mixed media installations made from found objects that the artist then assembles into large shapes and words using lace and tulle to conjure a subversive visual mood that’s part feminine, part masculine. Much of Hlobo’s work uses the Xhosa language, and he draws frequently on the rituals of his Xhosa roots to explore the complexities of his African identity. It has proved a winning formula–sculptures such as “Visual Diary,” 2010, which uses household Xhosa phrases, made waves on the international art scene. Gallery representation at Lehmann Maupin and fresh interest from collectors followed. In 2008, Hlobo’s status as an artist with international crossover was solidified with an exhibition of his work at Tate Modern in London. Since then, he’s continued to challenge contemporary thought on some of the most pressing issues for African people. His imposing bird-like sculpture “Iimpundulu Zonke Ziyandilandela”, 2011, greets visitors as they enter Zeitz MOCAA. Most recently, he’s been interested in natural Afro Caribbean hair, a subject he talked about in his 2017 Performa commission The Parable of the Sower: “Referencing hairstyles from West Africa—from a long time ago…will help us reimagine the present and the future,” he said of the work.

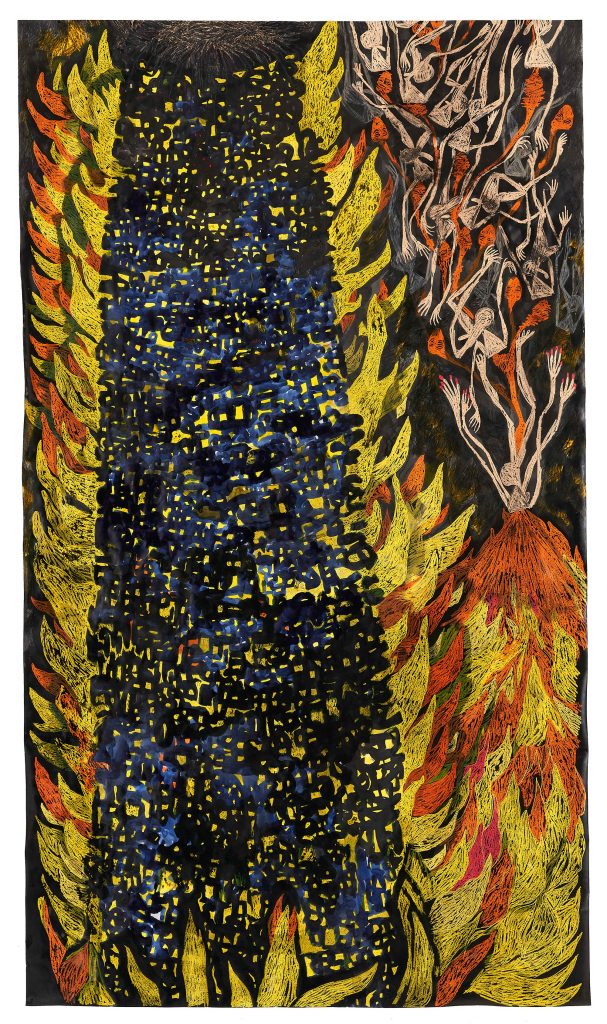

Lady Skollie

The experience of growing up as a mixed race woman in post-apartheid Cape Town, South Africa, underpins the work of Lady Skollie, otherwise known as Laura Windovogel. After a teacher noticed her talent for painting at aged six, she was sent to a Model C school—schooling institutions that had been designated for white children only until the end of apartheid in 1994—and she was one of the first black students to attend. Skollie stayed at the school until she was 18 and when she left she went on to create political paintings that reflect the realities of women’s lives in South Africa. Works like “Pink dick: sometimes I reluctantly reflect of all the times I’ve allowed my pussy to be colonised,” 2016, deal with the race issues that still endure 24 years after apartheid and the continued racism in South Africa. In particular, the artist is interested in starting new conversations about rape culture in her home country. Her 2016 painting “Cut-cut, kill-kill, stab-stab” deals with the gaslighting of womens faces when they’re reporting cases of sexual assault to the police. Represented by Tyburn Gallery in London, Windovel is creating new work that looks at the original South African Khoisan tribespeople and “the traditions of Khoisan storytelling, imagining a world of cave drawings depicting our pain”, she says.

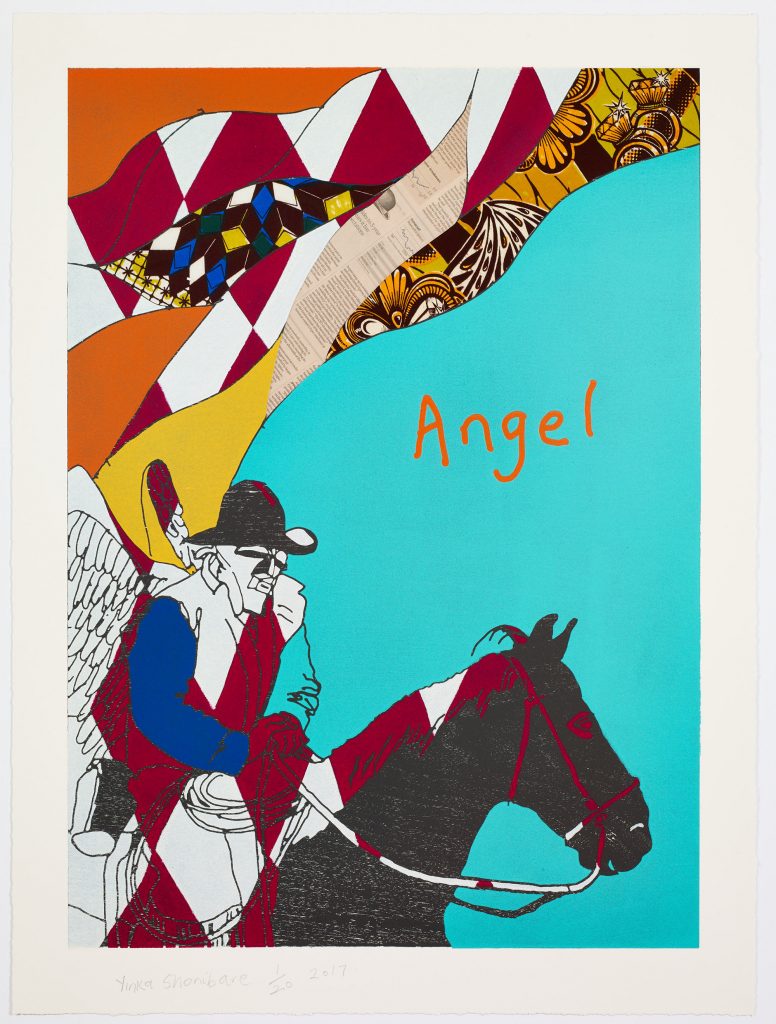

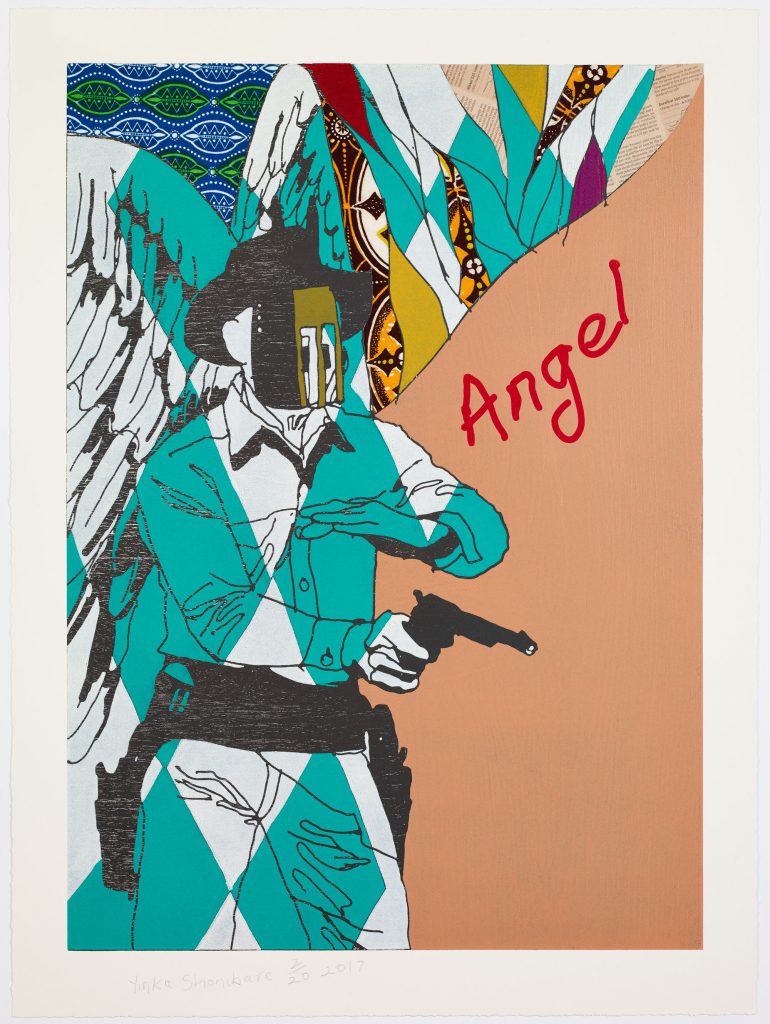

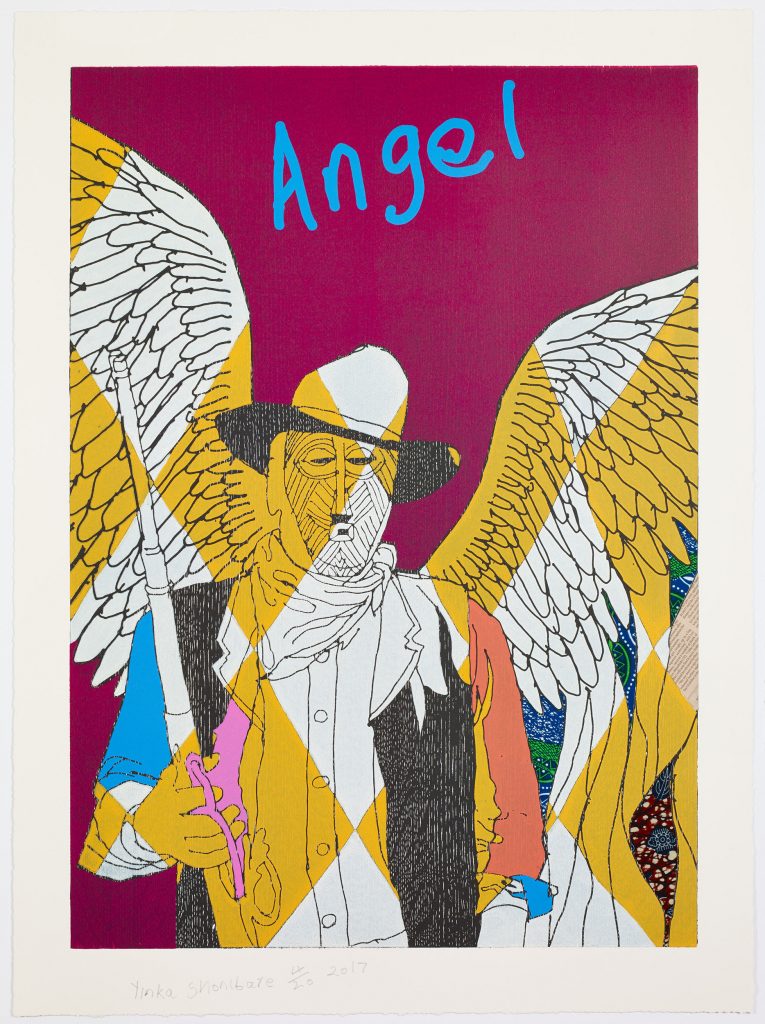

Yinka Shonibare MBE

A key part of the 1990s YBA scene, Yinka Shonibare MBE has been nominated for the Turner Prize, been elected Royal Academician by the Royal Academy of Arts and in 2010 was invited to create an installation on the fourth plinth in Trafalgar square, for which he presented Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle. Born in London, his parents moved the family to Lagos, Nigeria, when he was three. Shonibare moved back to London to study art aged 17 and since then he’s dealt with the complex and often violent histories of England and it’s abuse of West African people. Through one of his most recent works, “Cowboy Angels,” 2017, a series of woodcuts, he continues to discuss the enduring theme of African identity in the West. “’Cowboy Angels’ is the beginning of a series in which icons of power are being deconstructed by replacing their faces with African masks,” he says of the work. “The series will produce further prints exploring further deconstructions of power.” In March 2018, the artist revealed his new public work Wind Sculpture (SG) in New York’s Central Park in the middle of Doris C. Freedman plaza. “The work was inspired by ‘Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle’. The sails – which are made using my batik textiles, also more generally evoke a transatlantic migration, such as the African diaspora,” Shonibare comments. Made with support of the Public Art Fund, the 23-foot work is one of his most adventurous public outdoor sculptures and is among a series of similar pieces around the world. “In a way this work is also a kind of celebration and a tribute as well to migrants,” he says.