The Reluctant Specialist – The Evolving Practice of Ronan Bouroullec

For our S/S 2021 issue, TLmag35: Tactile / Textile / Texture, Zeniya Vreugdenhil interviewed Ronan Bouroullec to talk about the opening of the Bourse de Commerce, the designer’s connection with textiles, and how drawing helps keep him focused and creatively engergised.

It is difficult to describe the expansive nature of Ronan Bouroullec’s practice. With a career built over thirty years, the designer has worked alongside his brother Erwan to produce projects spanning – and frequently combining – the fields of industrial design, architecture, interiors, and exhibitions. Within this deeply collaborative and dynamic practice, Bouroullec has also stretched the constraints that characterise industrial design to create numerous technical and experimental textile projects. From collaborations with Kvadrat and Nanimarquina, to large-scale projects such as the interior of the Bourse de Commerce in Paris, Bouroullec approaches textiles with thoughtful observation and sensitivity to detail, creating flexible, atmospheric, and tactile designs. TLmag speaks with the designer about the joy of naivety, the necessity of a humble approach, and the intrinsic value of comfort that textiles lend a space.

TLmag: How do you describe your practice, and what is important to you in the projects you take on?

Ronan Bouroullec (RB): We are interested in a lot of subjects. I get stressed by the idea of repeating myself, which is probably the reason behind working across all of these different fields. Because we have had success, we can be patient and think about many types of projects, so the map of our practice is quite large. I think this is one of the beautiful aspects of this discipline, that as a designer I do not feel at all like a specialist. I like being a generalist, and working with specialists. I think it’s a question of attitude and being humble; with enough empathy, you can work across a lot of subjects. As someone who works with specialists, I try to help them reinvent some aspect of their technique, thoughts, or tools, and I try to approach this process with delicacy and humility.

TLmag: How do the roles and interests in your practice shift between yourself and Erwan?

RB: Erwan and I have been working together for almost twenty-five years. At the beginning Erwan was my assistant. It was a very enjoyable period when we were extremely naive, and starting to work for companies like Vitra. After some years, Erwan became my associate and since then, he and I have developed more specific interests. Erwan is focused on very technical projects, such as those with Samsung while I have a need to do a lot of different projects and to have physical results. I’ve become extremely interested in the question of the city, and how to open our work to a wider audience. Craft is also important to me, and the question of how to continue to challenge myself with new subjects and new approaches. As I said before, I am afraid of repeating myself. I think the most joyful period in this discipline for me was probably when I started; I like this position of being naive in front of a question and trying to escape all the specialist traps. The problem now, after thirty years of work, is that I’m starting to become a specialist. That’s why I need to be confronted by various types of questions at the same time. It keeps a certain freshness, or at least it’s my method to stay fascinated.

TLmag: I noticed that your drawings have served as inspiration in several of your textile projects. How does drawing influence your work?

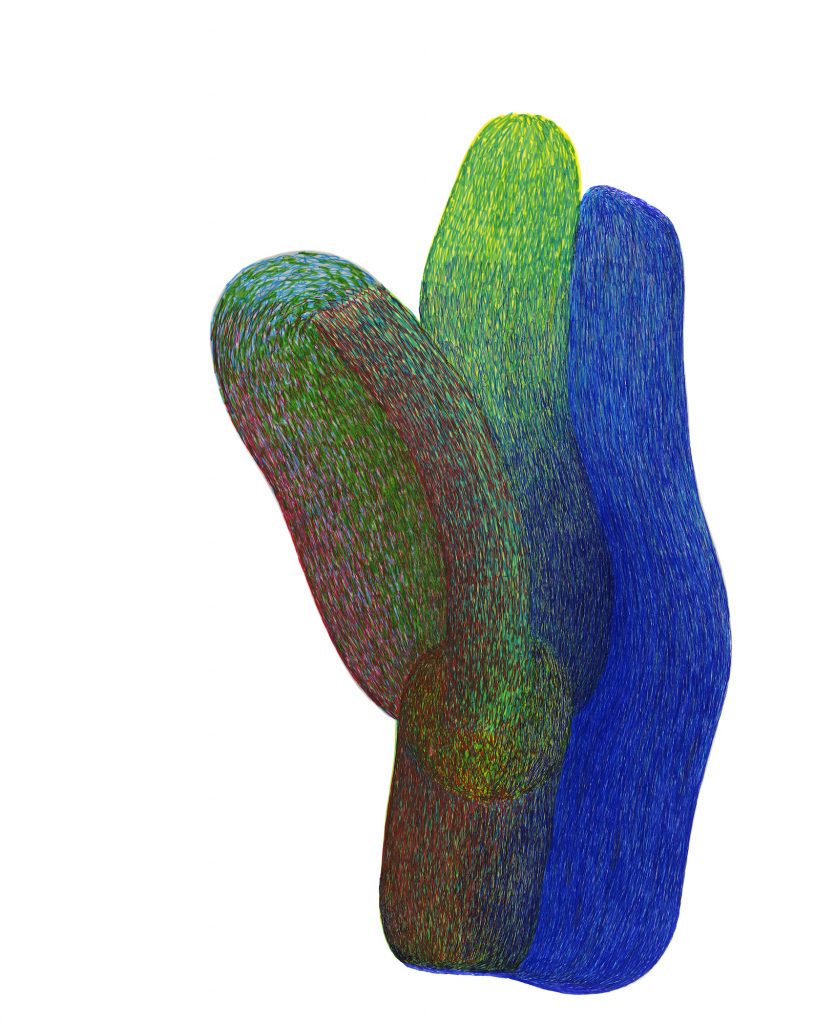

RB: In industrial design, the timeline between the starting point of an idea and its existence as a real object is years. It involves a lot of people, and a lot of discussions. It’s a long journey, and I like having constraints, but it can be a very frustrating discipline. Drawing has always been a sort of companion for me; a way to beat melancholy or sadness. I like this very direct way of expressing things; it’s a pleasure. It was always more of a secret aspect of my work, but then we decided to start showing them as part of our research.

TLmag: You’re originally from Brittany, where I understand there is a strong tradition of embroidery and textile crafts. Do you think that this was perhaps one of the starting points for your interest in textiles?

RB: We grew up in the countryside in Brittany, which is a part of France with a very specific regional language and craft. It was only when I left the countryside that I understood how important these surroundings and culture were for me. The textiles and embroidery were there, but I think I was influenced more by a certain countryside way of life: when something is broken, you try to repair it; when you go to buy something new, you choose it carefully. So, I grew up in this type of family, with this type of ethos, and even though I was against it at the time, I think it was the most important thing that I learned as a kid.

TLmag: Many of your textile works are based around the idea of partitioning space, and they also have a very integral sense of balance, structure, and scale. What is your perspective on the relationship between architecture and textiles?

RB: Partitioning space has been a theme in our work since the beginning; every year we work on new solutions, new typologies, new projects. The first project based on this was when we were invited to design the Kvadrat showroom in Sweden. When Kvadrat first invited us, we refused because we thought we weren’t good interior designers. They came back, and it’s always flattering when someone insists on working with you, and we eventually agreed. That was the first time we produced a wall system in textile. It was called North Tiles. What was interesting was that when you entered the space, sound was completely absorbed. We also think a lot about the atmospheric quality of space. Sometimes this is forgotten in architecture – how to feel well in a space. This project was the first time that we found something new that generated a very high value of comfort. For me, textile has always been something very important, because it immediately generates a quality of life, which is one of the most important aims of our discipline. It’s really a question of how to create and build new environments. Aspects like the quality of sound, the way the light is filtered or not, the quantity of light entering, and the variation of texture are so important to consider.

TLmag: At what point do you feel most energised within a project? What brings you the most joy?

RB: I try to have patience and excitement for each project. I am so lucky to have a lot of requests and to be able to choose which projects I accept. This morning I was speaking with a chair manufacturer in Japan. It seems banal, to design a wooden chair, but when it’s done with good people, and with so much patience and quality, it’s a treasure. I’m also working on a pavilion to present an art piece by a friend, but there is no money at all so we need to do something marvellous with nothing, and I like that a lot. We just finished a project for the new Francois Pinault Foundation in Paris, at the Bourse de Commerce. This project is a mix between urban and industrial or interior design, because we designed the space around the building, and also everything inside, from the carpet to the curtains, the chairs to the chandeliers. It took three or four years, and as a project it is representative of our various abilities as a design firm.

TLmag: How does the way you see or approach the process of textiles change?

RB: Textiles are the only material which I do not understand technically at all. If I design a wooden chair, I know exactly how to assemble the pieces of wood. Very often the quality of a design lies in the use of materials or the way of linking the piece together. Connections hold a lot of importance, and are a big part of the vocabulary of our work. But textiles are something that my brain is too small to understand. It’s very satisfying for me, bizarrely, because when I design textiles or carpets we share our guidelines and very precise drawings, and these are translated by a textile engineer. Sometimes I become stressed because I have to find a different way of translating things. In this way, we build textile projects in a totally different way than the others, but this is also what I like about working with textiles – it’s full of mystery and surprise. It’s a magical process.

Galeriekreo.com

@galeriekreo