Under Cover

Working with textiles and decorative fabric elements, these five artists are creating and capturing body covers, face masks, suits and sculptures that speak of preservation, identity, transformation and surrender.

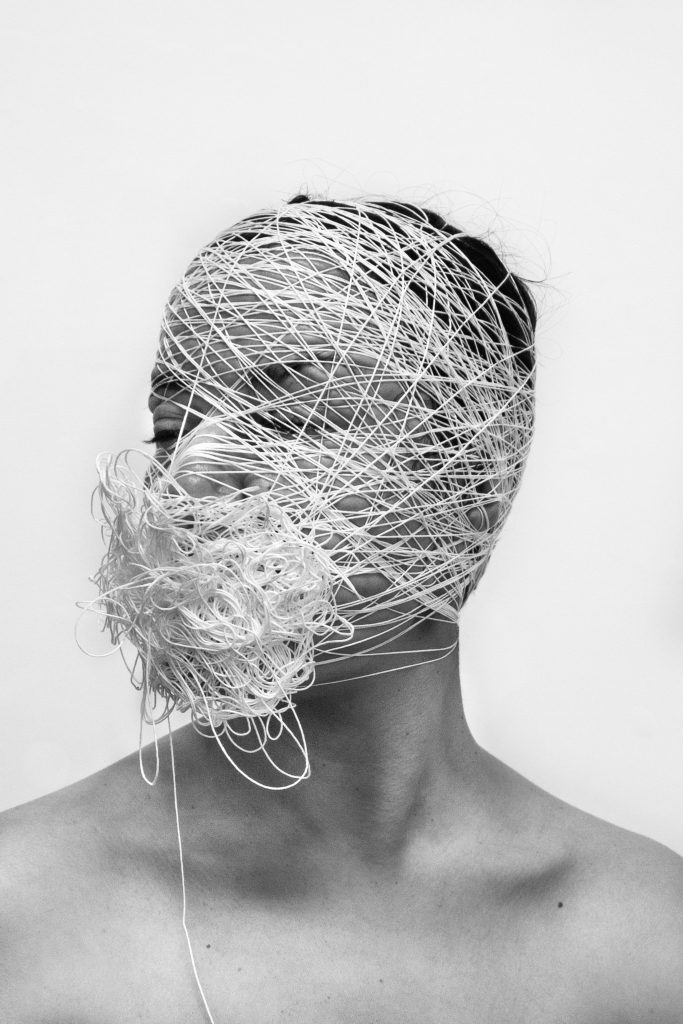

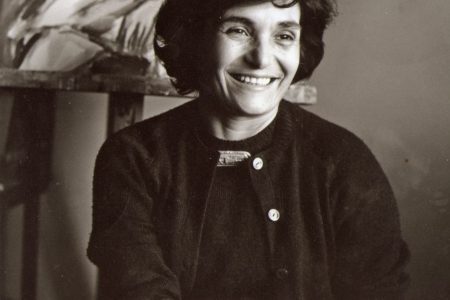

Damselfrau

Magnhild Kennedy, better known as Damselfrau, calls her masks “action-objects” – works that are guided by the materials she selects. The self-taught Norwegian artist, who resides in London, veers away from pre-planned decision-making or sketching. Rather, she allows her drawers and boxes piled with collected materials – from antique silks and sequins to colourful pom-poms, tea towels, tassels and lace – to dictate the making process. “I try to think as little as possible and just play,” she says.

“I love materials that have been around the block, and I like taking apart old clothes that have done their work. If they have been mended and sewn on through the years, even better.”

By giving all materials equal status, a combination of any texture, colour and embellishment becomes possible. It is thus that Damselfrau’s masks defy definition. There’s could be a touch of Baroque, hints of folkloric iconography, inklings of science fiction, or an under- current of fetishism.

“Masks are transformative,” says the maker, who keeps her creations open to interpretation. “There’s privacy and powerful expression in there.”

@damselfrau

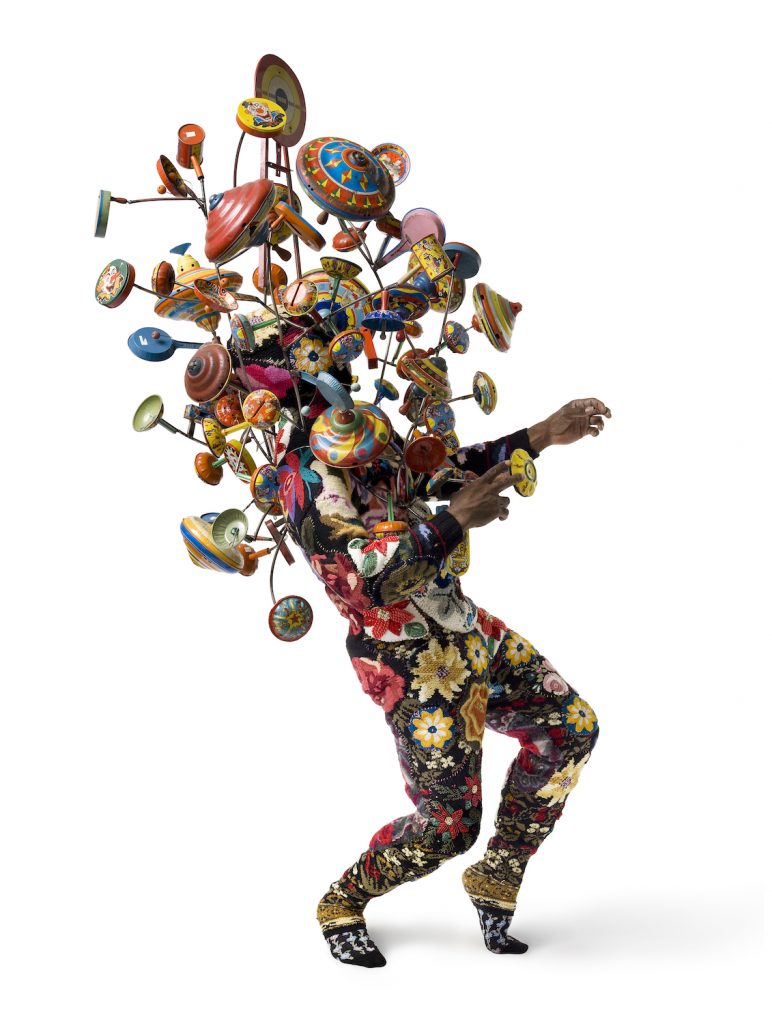

Nick Cave

US multi-disciplinary artist Nick Cave has created more than 500 Soundsuits since his first in 1992. Although that debut piece was made of twigs, he has since fashioned Soundsuits from found and fabricated materials that range from crocheted doilies to mix-and- match upholstery, pipe cleaners, buttons and synthetic raffia. Much of the time these Soundsuits are donned as performance pieces, their materials sashaying around moving bodies, creating subtle sounds. Such animation, often accompanied by rhythmic music, calls to mind ceremonial dances found around the world, allowing the colourful suits to represent an eclectic multi-culturalism that conceals race, gender and class. “When you wear them, you are shielded. Your identity is no longer relevant,” says Cave. “It’s really liberating if you know how to surrender.”

By surrendering to the suit – even as a viewer – one opens oneself up to the unfamiliar, a theme that is ever-present in this other-worldly work of figurative sculpture. “I want people to look at what surrounds them differently,” says Cave. “In negotiating the potential of a material we can make it extraordinary, and this allows us to think of other ways we can exist in the world.”

@nickcaveart

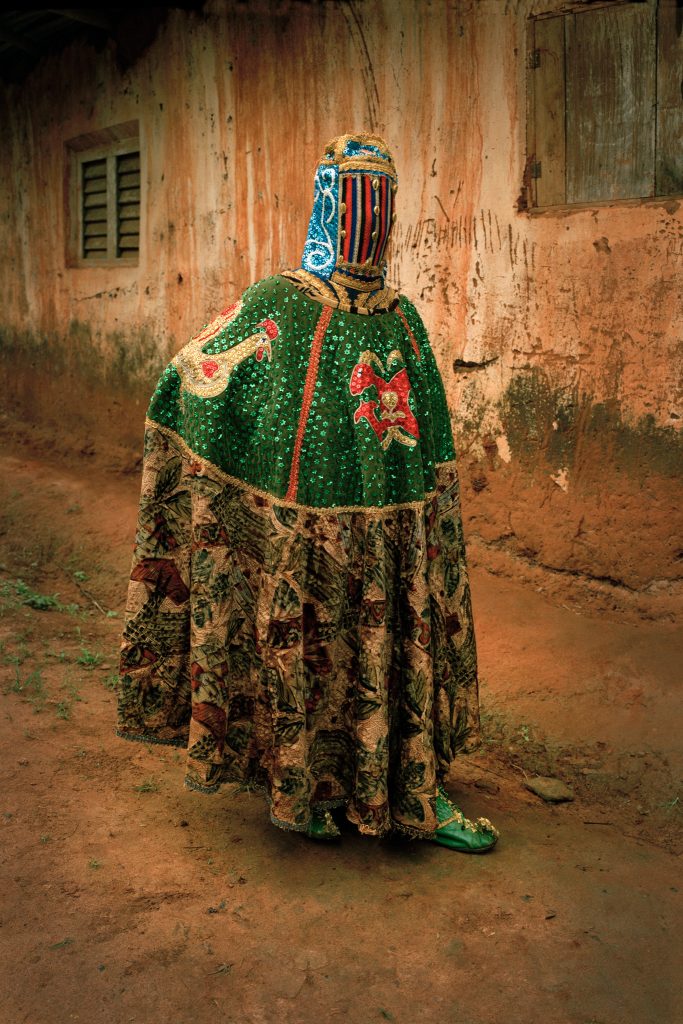

Leonce Raphael Agbodjelou

Even while working as an assistant to his famous photographer father, Leonce Raphael Agbodjelou was drawn to the textiles and textures of his West African homeland Benin. “We would put together outdoor studios using painted backgrounds and local textiles where clients would pose and show off,” explains the man who is now revered as a photographer in his own right. “Fashion, costume and props like plastic flowers are very common in West Africa, and have always been used in the traditional studios to show style and taste.” Agbodjelou continues to use rich African fabrics as backdrops, and his subjects – everyday people in Benin’s capital of Porto-Novo – are usually dressed in equally enticing textiles, caught between tradition and modernisation. It is a colourful way for the photographer to document the vibrancy of his culture.

This dynamism is no more evident than in Agbodjelou’s Egungun series, in which he has immortalised the Yoruba performers who guide the deceased into the spirit world and protect their communities from misfortune. For the photos, the Egungun, cloaked in masks and dazzlingly embroidered robes, stand in front of textural mud-brick walls, in poses that hint to their humanity.

Says Agbodjelou, “I have grown up among these traditions, and I want my photographs to resonate with the cultural understanding of an insider.”

www.jackbellgallery.com/artists/25-leonce-raphael-agbodjelou/overview

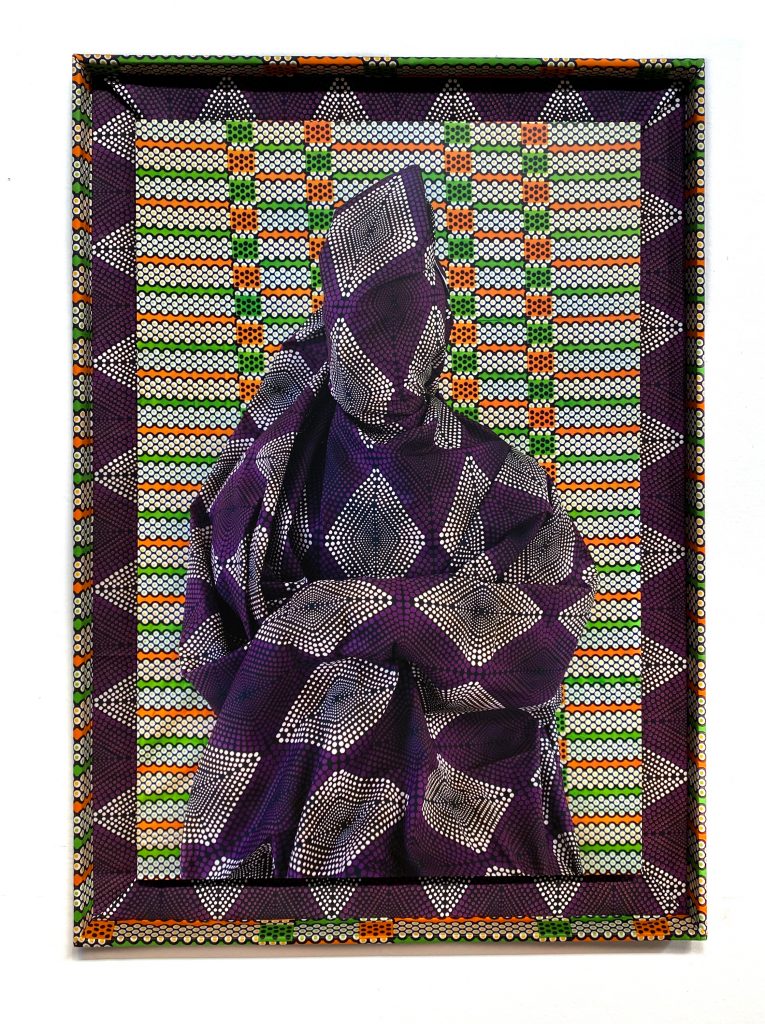

Alia Ali

That Alia Ali has received a Creative Activism Award from the Cultures of Resistance Network speaks to the artist’s pursuit of social justice through her conversation-sparking forms of expression. Living between Los Angeles and Marrakesh, and armed with a BA in Studio Art and Middle Eastern Studies, and an MFA in Photography and Media, Ali produces photographs, videos and installations that reflect on issues of identity.

“My work explores cultural binaries, challenges culturally sanctioned oppression and confronts the dualistic barriers of conflicted notions of gender, politics, media and citizenship,” she says.

Through her art, which uses pattern and textiles as its message, Ali encourages viewers to confront their prejudices, addressing the politicisation of the body, histories of colonisation, imperialism, sexism and racism, moving past language to offer an experiential look into self, culture and nation.

“I believe that textile is significant to all of us,” she explains. “We are born into it, we sleep in it, we eat on it, we define ourselves by it, we shield ourselves with it and, eventually, we die in it. While it unites us, it also divides us physically and symbolically.”

Through her use of such materials, she highlights the fabricated barriers in society that can both segregate and connect us. “What do we fear discovering beneath the cloth?” she asks.

@studio.alia.ali

Troy Emery

“Fake taxidermy” is how Melbourne-based artist Troy Emery describes the animal-form sculptural work he produces.

“I’ve always been fascinated by natural history museums and how we can learn from and aesthetically appreciate such exhibitions,” he says of his inspiration. “In these environments, taxidermy is presented as a preserved symbol of extinction… a strange duality.” In his own play on duality, he covers fibreglass forms (usually produced for the taxidermy trade) in vibrant textiles, using the hand-worked values of craft to merge with the formal qualities of sculptural art. Dressed in domestic decoration and fabrics often reserved for dance costumes – ranging from pompoms and fringing to tinsel and sequins – the somewhat amorphous shapes are stripped of any classification, and are transformed into lost animals that warrant preservation in museum displays. “When the pelt covers the form, it becomes like a trophy of an endangered or extinct mythological creature, which could be both an artefact and an artwork,” says Emery.

Emery’s oeuvre has crossed boundaries into fashion, with the artist producing an evocative capsule collection for Melbourne Fashion Week last year. His is also regularly commissioned by Hermès for its luxurious window displays.

@troyemery

This article originally appeared in our Spring/Summer 2021 issue: TLmag35: Tactile/Textile/Texture

Cover image by Damselfrau