Wanås Konst: Unhurried Experiences

TLmag talks to Elisabeth Millqvist, the artistic and co-director of Wanås Konst: a beautifully isolated Swedish sculpture park that breaks the behavioural barriers of the white cube – and whose open collaboration with artists ignites a refreshing approach to looking at and experiencing art.

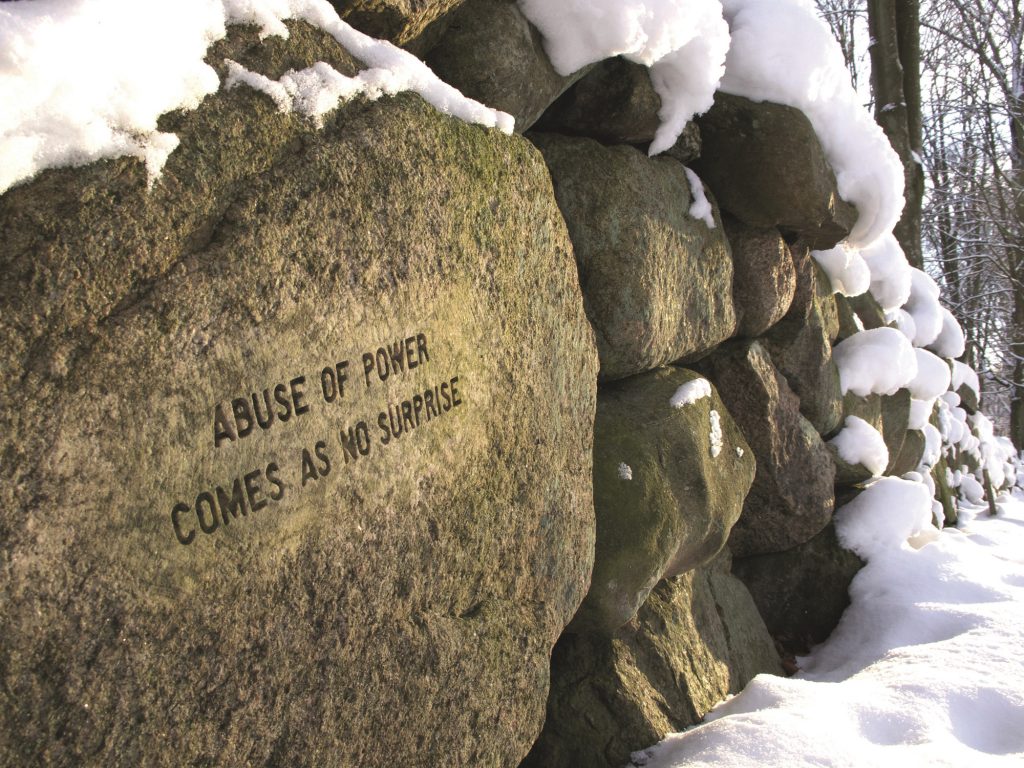

Hidden away beneath the tall Scandinavian trees of southern Sweden and covering over 40 hectares of land, Wanås Konst – Center for Art & Learning’s park (and main exhibition space) coexists amongst Wanås Restaurant Hotel, Wanås Estate as well as a privately owned 15th-century castle. Visited by approximately 80 000 visitors per year, this beloved park is also the permanent home to 70 works by the likes of Igshaan Adams, Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg, Yoko Ono and Jenny Holzer (just to name a few). Since its founding in 1987, more than 300 artists have been invited by this unique art institution to take part in temporary exhibitions, with a chance that their works might stay for good. This summer’s large scale temporary exhibition, titled ‘Not A Single Story II’, is a further development of the large exhibition that Wanås Konst’s leadership duo co-curated at the Nirox Foundation sculpture park outside Johannesburg in 2018. With a concentrated selection of artists and some new names, the exhibition is transformed into a new place and brings together artists and artworks that are influenced by location, history and identity. TLmag sat down with artistic and co-director Elisabeth Millqvist on her broad understanding of sculpture, maintaining a flexible practice, the opportunities and challenges that outdoor curating offers and the rare possibility of continuity that this newest exhibition has made possible.

TLmag: You became co-director of Wanås Konst, the sculpture park run by the Wanås Foundation, eight years ago. How did you go about building your own distinct exhibition programmes for a sculpture park that already had such a rich history and set artistic process?

Elisabeth Millqvist (EM): I was interested in creating another relationship to the audience, and making that or giving their visit an unmissable presence. This idea of questioning whether the viewer can be more than ‘just’ a viewer, or if the line between artist and audience can be less strict and more flexible, felt quite essential to add. I think that is really well exemplified when you go to Yoko Ono’s ‘Wish Trees’; she makes the viewer a participant by working with instructions. I think that is important in our time, where we like to self-edit. Another approach is one I took over from artist ErwinWurm, who at one point said of his practice, that he decided to call everything he does a sculpture. I think we have that open-minded approach as well: what if we think of any work we situate as a sculpture. In a way, the remoteness of Wanås, combined with this way of thinking, has made it relatively easy for me to have a challenging and daring programme. I feel like nobody is looking over my shoulder, and we can take risks and really go for what we believe in.

TLmag: What does the process of choosing your artists look like?

EM: We mainly invite the artist ourselves, and that is basically how it has always been; in the beginning, it used to be a postcard or a letter, and today it’s mainly by e-mail. We get a lot of requests and suggestions, and even though most of the time these aren’t possible, we’re delighted to receive them because it’s another way, besides our own research, for us to stay up to date with what other artists’ are doing and what they’re up to. The whole process broadens our minds and allows us to yet again open another dialogue with the art scene at large.

We actually really like to be in contact with the artist directly and start a conversation. During this first meeting, we want to make it clear that we’re not interested in a specific artwork or in one particular site in line with the chosen artists production, but more interested in working together and exploring new avenues and opportunities. This is also the case because a lot of times, we also work with artists that are not (only) associated with outdoor or land-art. After initial contact, we ask them to come for a site visit and stay for at least one night, which is a central part of our practice. That way, they can explore the surroundings and see the place and nature in different kinds of light. After the site visit, we ask the artist to come back with an idea, and from there, we can discuss different possibilities; what kind of time frame is needed, when or how it will happen. We support with research and knowledge in production as well as with economical means — sometimes the artist has everything figured out, but we’ve found that usually an artwork starts with this one idea with at least 10 different people are involved in, and by the end of the year, the work is likely to be seen by at least 100.000 people. It really has its own journey.

TLmag: It sounds like the practice of Wanås Konst is quite flexible and artist specific…

EM: We really do like to remain quite flexible. After we set the time frame and start work on the project, we discuss and decide with the artist if they need to be here for a short time, visit sporadically over a period of time or if it’s better for them to work on the site for an extended period of time because they actually need to be present to create the work. It may seem a bit strange because we often have people wondering if it’s a residency or a commission. In one way it could be both, it could be one or the other, it could also be none of the above. We like to remain flexible and truly work in the artist’s and artwork’s best interest.

TLmag: What opportunities does outdoors curating offer you?

EM: It gives me access to, what I like to frame as, an unhurried art experience; it can take time, and that allows you for much more reflection and engagement. I also think that it increases accessibility. Most museums are very engaged in thinking about how to make their audience diverse through outreach programmes and advertising — but here, our biggest issue is that we’re in a remote location. Having said that, the way people can discover the work here increases its accessibility. Visiting Wanås’ sculpture park could be a stroll in a park, foraging for mushrooms or walking your dog — there is no residue of that intimidating feeling that many experience when visiting a white cube or museum. We don’t need to lower the thresholds because we have none. I think that this is very exciting, and for me, it has allowed me to think beyond “normal” exhibition formats and programming.

TLmag: And on the opposite side of that, what are the biggest challenges you face?

EM: Museums often like to control everything; the climate, the security, the visiting hours. Whereas, at Wanås Konst, we can have visitors at day or time they feel like coming — rain or shine. Yet, being outdoors does affect the works, and preserving them is a constant challenge. Materials like stone and bronze are durable materials, but many of the artworks in the park use other experimental materials as well. The questioning and thinking of how certain materials will age is really quite complicated and leads us to consider how we think about permanency in outdoor spaces. Sometimes, artists specifically ask us to allow their works to “naturally decay”, but I’ve found that even that is a difficult concept to grasp. If we find that a tree that has fallen on an artwork after a storm, is that natural decay?

Another thing is security. I’ve never been to a sculpture park where every one of the works is guarded, and it’s also not an option for us as the sculpture park is not fenced in. Yet, how can we install a work that people will want to interact with, without taking it apart or hurting themselves in the process?

TLmag: Could you walk us through the process of how an artwork comes to being a part of the site?

EM: We think that art and artist’s voices are essential in our society, so being in close dialogue with artists and offering them an opportunity like this is vital to what we do. Like I said before, it’s of the utmost importance to us that artists come to the area and see it for themselves — and we also ask for the artworks to be constructed on-site usually. We think this not only creates a stronger relationship between the artist and our site but also our visitor’s relation to the artwork. Art doesn’t just “happen” — it’s an extraordinary thing to be able to come to the sculpture park and follow the process of this artwork’s creation.

TLmag: How do you feel that this connection with site and nature, combined with the isolation of Wanås itself, influences the methodology of your artists?

EM: I think that it makes the artists feel a bit more experimental — a bit braver. Because they’re so distant from their everyday surroundings, so they get the courage to try out something new or something they’ve been wanting to do, but life got in the way of it. I think this isolation-like quality not only influences the artists a lot but our visitors as well. When visiting a museum or gallery, people often just stick around for a short amount of time: they make the round and then continue to run their errands, meet with friends. Here, it’s more likely that they’ll wander around, take the wrong path and end up being here for hours on end, and finding works serendipitously. I think that’s a fantastic quality.

TLmag: Earlier this month Wanås Konst opened its latest exhibition titled ‘Not A Single Story II’. How does this temporary exhibition situate itself with the permanent artworks in the park?

EM: Our new exhibitions always have a big presence, and we make sure they get a lot of attention. It also has a bit more of a fluid presence in a way. It’s an exciting environment to be in because the works on permanent display and the new exhibitions always come together organically. As existing work will always be standing right alongside the more temporary pieces, it will become a part of the dialogue. That’s why, as a curator, you never really know if people see the temporary exhibition as how we envisioned it.

TLmag: This exhibition is a further development of a substantial exhibition that you co-curated at the Nirox Foundation sculpture park outside Johannesburg last year. How did this collaboration come about, and what led to the creation of this second chapter?

EM: In the last five years we’ve had this dialogue with Nirox Foundation and, last year, they invited us to make an exhibition at their sculpture park outside of Johannesburg. That was such an exciting opportunity for us, and it felt crucial for us that, in a country with such a charged history as South Africa, we Europeans should not come in and tell others what we want to do. Instead, we used our know-how, as people who run a sculpture park and followed our tradition of starting off with the history and place of the site, the land, itself and the sculpture park’s male-dominated history. From there, we found that there were specific issues that we wanted to challenge while still wanting artists to have the freedom to create whatever they wanted to. That’s how we came about calling the exhibition Not A Single Story, relating to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichi’s TED talk ‘The Danger of A Single Story’, to really show the need for multiple perspectives. After having done that exhibition last year in May, there were so many exciting processes that took place, so we got a possibility and decided to go for making another version of it in our sculpture park. In a way, it was almost inherent in the title, not a single story, to make another chapter.

TLmag: How has the first exhibition, that was situated in South Africa, been translated into its Scandinavian context?

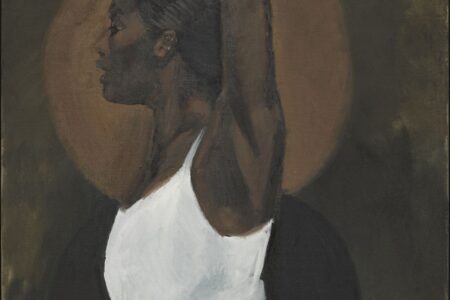

EM: This continuation is incredibly rare. Usually, when we work on a new idea, we only have one iteration of the artists’ work. Once it’s done, we see what could have worked better, or the artist realised what aspect of the work they wished they had focused on more, but we can only internally learn from that. Here, we made a concentrated version of the first exhibition with 8 instead of 25 artists. The selected artists (Latifa Echakhch, Peter Geschwind & Gunilla Klingberg, Lungiswa Gqunta, Lubaina Himid, Marcia Kure, Santiago Mostyn and Anike Joyce Sadiq) were the ones that, at the end of the first iteration, they happened across an exciting part of their process that could be further explored. In Sweden, ‘Not A Single Story’ get’s a slightly different content, I think it connects to a dialogue of resisting opposition between the “us” and “them” discourse, highlights issues concerning multiple identities and brings forward the implications of what histories that are told and which ones are invisible.

Wanås Konstsculpture park is open daily, all year round, from 10:00 to 17:00. The Art Gallery and indoor installations are open March – December. ‘Not A Single Story II’ will be on view until November 3, 2019.