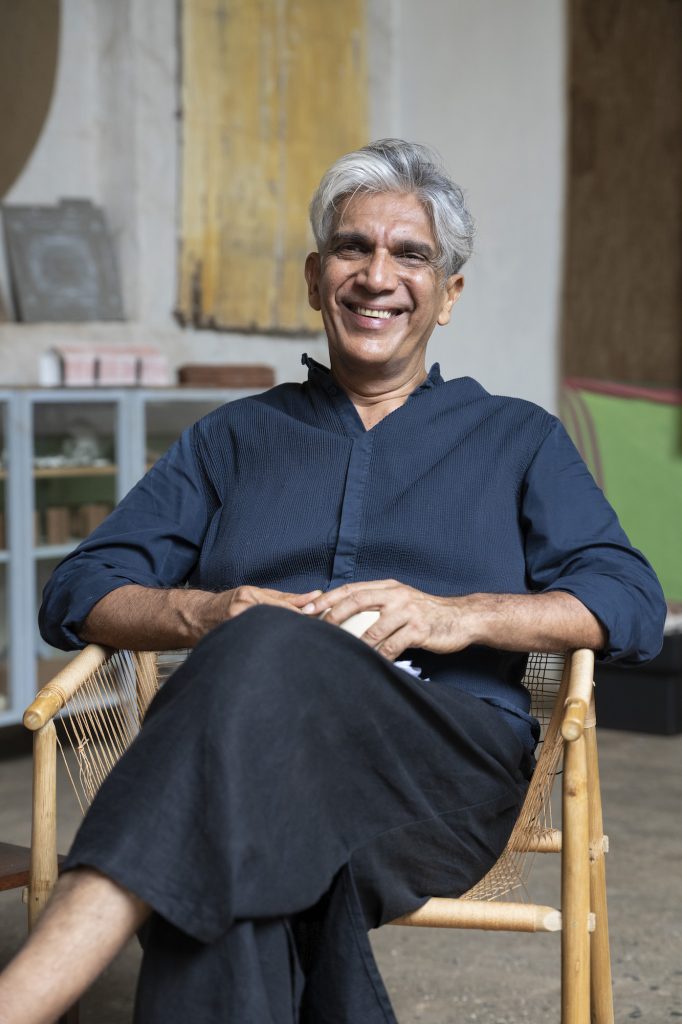

Bijoy Jain: The Breath of Life, A World of Being

For our 2023 issue: TLmag39: The Culture of the Object, Lise Coirier spoke with Bijoy Jain ahead of his solo exhibition at the Fondation Cartier in Paris, opening December 12, 2023.

This exhibition, titled “Breath of an Architect,” curated by Hervé Chandès and Juliette Lecorne, reveals intimate and emotional facets of the works of Indian architect Bijoy Jain. His work serves as a source of inspiration, contemplation, and quietude for everyone. Offering a space of silence and communion with the elements (water, air, earth, light), the suite of installations at the Fondation Cartier opens up to reverie and a promenade within Jean Nouvel’s building in Paris. Universal and cosmic, Jain is not the only central figure in this exploration of art and architecture. He connects us to the profound beauty emanating from artistic gestures by engaging in dialogue with two contemporary artists: Chinese painter HU Liu, who resides in Beijing, and Turkish-born Danish ceramist Alev Ebüzziya Siesbye, who lives in Paris. Take a breath! Slow down.

Lise Coirier: You were born in Mumbai, but did your family originate from this city? How would you define your roots, given that you have studied and worked in the US and in London and have taught at Mendrisio and Yale, among other places around the world? You have also received numerous awards across continents, such as the Dean’s Medal of the University of Washington in St. Louis (2021), the Alvar Aalto Medal (2020), and the Grande Médaille d’Or from the Académie Française d’Architecture (2014)… How do you feel now, and what might be the next step after receiving so much international recognition?

Bijoy Jain: My parents came to Bombay for their medical studies in the 1940s. The city, which became Mumbai in 1996, was much smaller then. My mother was from that region, and my father was from Rajasthan in northern India. I have never worked for recognition, but I have always been curious about the world. I was fortunate to be sent to the United States at the age of 14 due to my talent in swimming. Although it wasn’t easy, and I felt homesick, this exposure allowed me to travel across continents over the past decades and delve deeper into myself. This resonance I have felt toward energy and the osmosis of my body and soul formed in water may be directly related to my practice as an architect.

L.C.: You established your first studio in 1996 before founding Studio Mumbai twenty years ago. Has the studio evolved as the framework for all your research and activities? How do you organize it on a daily basis? It seems that numerous experiments are taking place there within this interdisciplinary collective of architects, engineers, master builders, artisans, and artists from various parts of the world. How would you define your creative process?

B.J.: Studio Mumbai is spread worldwide; it’s an open-field studio. I have questioned how to build a structure that allows for transmission while maintaining its flexibility and human freedom. The practice at the studio is centred on presence and the repetition of gestures. Despite traveling extensively, I can easily work from my iPhone.

L.C.: The use of materials at your studio is diverse, but what is the common thread among them? Is it nature or grace? I have listed a number of them: bamboo, bricks, cotton threads, cow dung plaster, jute, karvi (made of bamboo, cow dung, jute, thread, lime, pigment), lime, natural pigments, plants (turmeric), silk cocoons, strings and yarns, stone, wood.

B.J.: The essential material is breath. The connection to natural and local materials combines in an economy of means where space and object are harmonized in a choreography of movement. We encounter the same phenomena in the East and the West. We are the only ones capable of discovering the grace of giving and receiving.

L.C.: Hand-carving sculpture through direct gesture appears to interest you particularly. Will this become an even stronger direction for your future, much like it was for Isamu Noguchi in connection with his deeper beliefs and Buddhism?

B.J.: I have recently been interested in setting up a small bronze foundry, which would lead me to work with metal and fire. This curiosity about craftsmanship is a way for me to map and explore this end- less new territory, which connects back to the roots of my Indian traditions, such as Chola and Gandara bronze sculptures. When hand-carving stone, what appeals to me more is the sound rather than the visual outcome. I am more interested in materiality as a source of deep haptic experience and consciousness. This journey of interest occurs when you discover something about yourself.

L.C.: How would you express the essence of your exhibition concept at Fondation Cartier in connection with the iconic building designed by French architect Jean Nouvel?

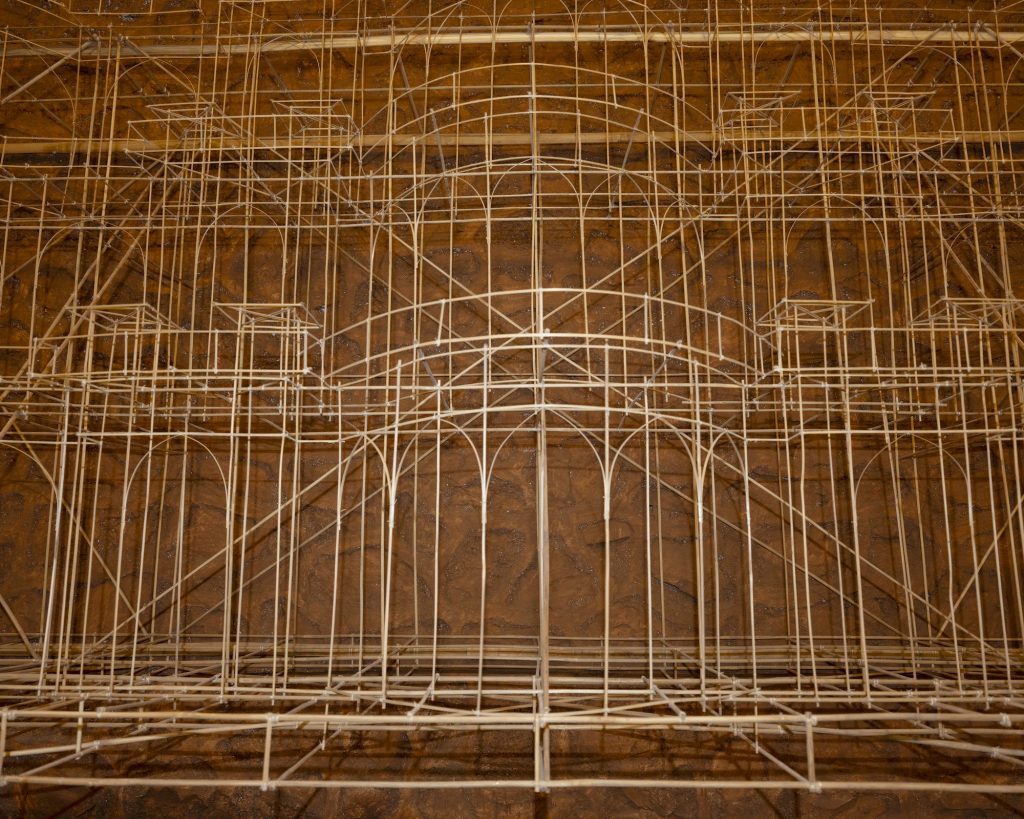

B.J.: My goal for this exhibition is to return to the foundations of Jean Nouvel’s building, removing walls and respecting the architect’s original vision. It’s a conversation with the architecture of Fondation Cartier and its garden, where all the layers blend to provide depth and meaning. Despite being enclosed, the inside and the outside meld to perceive the air, light, and the surrounding elements. Visitors will become inhabitants of the space, conceived as a transitional realm, like a room, a place, an ‘invisible city’ to quote Italo Calvino, composed of memory and desire, bridging the past and the present. I envision it with artefacts and fragments in which we find the foundation as a shelter. In an era of displacement, inhabiting a home, a refuge, is the essence of being. This exhibition at Fondation Cartier is not about the hand and natural materials but about how things can be crafted with breath. Everything I bring into these installa- tions is handmade, without relying on the Industrial Revolution and digital technologies. They are solely dependent on human breath, earth, water, and light.

L.C.: The creation of things is at the core of your life as an architect, not only in terms of buildings but also art for the inhabitants. How would you define your holistic values, philosophy, and approach to space, the environment, and materials?

B.J.: The inanimate comes to life thanks to the breath that flows back and forth. As human beings, we understand the inevitability of our destiny: we need to create a place for affection, care, and transition. By nurturing oneself, even when surrounded by all the world’s events, you maintain energy, and sentiment becomes the centre of gravity for your body and thoughts. Being aware of the karma surrounding you and impermanence, your relationship with life and death undergoes a profound transformation. You can test your capacity to breathe and blend air and light in a natural way to slow down.

L.C: Rooted in the relationship between humanity and nature, gesture becomes a source of experimentation from which beauty and grace emerge. Can you discuss the various modes of expression you are exploring, much like an archaeologist? By engaging in a dialogue with artists Alev Ebüzziya Siesbye and HU Liu, how do you involve people in your immersive installations?

B.J.: The exhibition offers multiple unique points of view and expressions. In a comparable ritual and repetitive mastery of gesture, Chinese artist HU Liu creates monochrome black works on paper using hundreds of graphite pencils, while Turkish-born Danish ceramist living in Paris, Alev Ebüzziya Siesbye, explores the weightlessness of clay, crafting vessels glazed in saturated pigments. All of them resonate deeply with materials, the play of light and shadow, and the perception of space in a unique sensory experience. For example, a stone oil lamp, one of our emblematic works, echoes early works in HU Liu’s career, where the artist dug into the mountains of Shaanxi province to fashion oil lamps. Architectural fragments, stone and terracotta sculptures, brick, bamboo, pigment, and threads intertwine into transitory and ephemeral structures that are both limitless and intimate. This land- scape is imbued with ethos, shaped by humans but in constant motion. “Breath of an Architect” brings together these forces, inviting an emotional relationship with space.

L.C.: Can you tell us more about the film co-produced by the duo Ila Bêka & Louise Lemoine in collaboration with Fondation Cartier? How does it reveal a different portrait of the Mumbai Megalopolis that we wouldn’t perceive as tourists?

B.J.: While the exhibition space is conceived as inhabited by a civilization in an unknown time, this movie, shot in the heart of Mumbai, was intense and filmed during the hottest and most humid period of the year. It felt like a scene from a Goya painting, driven by its own energy. It was “À bout de souffle” (breathless).

LC: “Breath of an Architect” is a beautiful exhibition, named after your book designed by Japanese art director Taku Satoh. What makes this book so special?

B.J.: More than a mere record, it conveys thoughts and sensitivity across continents with a sense of shared freedom.

Bijoy Jain / Studio Mumbai, “Breath of an Architect”, with artists Alev Ebüzziya Siesbye and HU Liu, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, France, December 9, 2023 – April 21, 2024. Catalog published by Fondation Cartier, December 2023

@fondation cartier

www.fondation.cartier.com

www.studiomumbai.com