Talking about ‘I See That I See What You Don’t See’

In this expansive interview, TLmag talks to co-curator Angela Rui on the (unseen) thoughts and ideas behind the Dutch contribution to the XXII Triennale di Milano.

The XXII International Exhibition of La Triennale di Milano, titled Broken Nature: Design Takes on Human Survival, aims to investigate the potential role of design in restoring the relationships between human beings with their environments, including both natural and social ecosystems. The thematic exhibition, which has a particular focus on restorative design, is accompanied by 21 international participants — of which the Dutch one is led by Het Nieuwe Instituut (HNI). Transforming the general theme through a ‘national’ lens, the three curators of ‘I See That I See What You Don’t See’ — design curator and researcher Angela Rui, HNI’s director of Research Marina Otero Verzier and HNI’s head of Agency Francien van Westrenen — began to look at the Dutch landscape’s relationship to light as one of the most illuminated countries on the globe. Utilising design as a tool for criticality and aiming to change the minds and behaviours of their visitors through a layered, non-binary, picture of the multi-species relationship with darkness, the restorative essence of the Dutch Pavillion lies behind revealing the invisible bi-products of our design solutions.

Elaborating on the unseen thoughts and ideas behind the exhibition, TLmag sat down with co-curator Angela Rui — whose ‘humanist’ approach to curating questions if there is a way for humans to return to a more holistic way of intention and relating to our environments.

TLmag: The theme of XXII Triennale di Milano turned its attention to human existence and persistence with “Broken Nature: Design Takes on Human Survival”. What was your first response this?

Angela Rui (AR): I remember that when Paola Antonelli (the head curator of the XXII Triennale di Milano) first announced the theme of ‘Broken Nature’, she mentioned a precise focus about “surveying our species’ bonds with the complex systems in the world, and designing reparations when necessary, through objects, concepts, and new systems”. This statement really interested us, especially considering the initial paradigm of the project, one that had to start from a specific national condition or perspective. That’s when we understood that light pollution, or light in general, could possibly be a strategy to connect to the main topic — not only for its natural and artificial properties but also because its metaphorical properties can allow speculation through different perspectives. Actually, the Netherlands has become known as one of the most illuminated countries in the world, and this is not only an expression of its 24-hour economy with an emphasis on production and growth but also a reflection of our changing relationship with our environment. For instance, they are so intense that the sky above absorbs and reflects that light. As a consequence, our view of the stars became limited, and the lack of dark influences the natural flora and fauna around these productive areas. Basically, there is no natural darkness anymore, so in the pavilion, the ‘broken nature’ corresponds to the broken bonds between light and dark, where the consequences are enormous; for our bodily condition (no sleep, infertility, burn out), mental state (no vision of access to the cosmos that goes far beyond our own), nature around us (disturbed lives of animals, plants and the environment as a whole). To place oneself outside of this system is almost an act of resistance. Through this perspective, we also realised that we started to see and read the Dutch landscape as something that has been designed from day one — and began to question if this can be redesigned.

TLmag: Would this ‘redesigning’ of the Dutch landscape be restorative?

AR: Right now, design has to be restorative. We are at this moment in time where we are trying to look at this condition and make aware to others that we really have so much less time than we first thought. There are no second chances, and if we don’t act now – not only will animal species become extinct in nature, but so will we. We should train to think about the fact that our behaviour always has direct consequences — for birds, insects and all other animals and — in the greater expansion of that thought — for climate change. Everything is interconnected. What we observe today is that designers became activists: they are not only playing a social role, but are very aware of political crises and try to move through its gaps and failures, or at least opening up spaces for transgression and possible changes.

TLmag: How did that immediacy work itself out in the exhibition?

AR: An interesting focus that we’ve had in this exhibition is to change the perspective of our visitors through the designs that we showcased. The projects correspond to a series of parallaxes, as metaphors. In a philosophical sense, the apparent displacements of the point of observation, permit us to also see differently. We asked designers, artists and researchers alike to focus on different ways of approaching and revealing this ‘unseen’-ness concerning the consequences of our actions. In the exhibition, all the works have revealed a mechanism that evidences how the current modes of understanding the environment are designed — simultaneously showing how we may redesign them in the future.

Through this idea of revealing through research, unveiling through an exhibition, design becomes restorative. We felt that the first step to fixing things is to be critical, and to ask your public to look at things through a different perspective — and hopefully change their minds and behaviours with you.

TLmag: The title, ‘I See That I See What You Don’t See’, is quite a tongue twister — could you tell us a bit more about it came about?

AR: We borrowed our title from a speech, then published in a booklet, given by Dr F.J. Verheijen in 1976 when he was awarded the chair in Comparative Physiology at the University of Utrecht. His dissertation focused on the influence of artificial light on animal behaviour, calling for a direct observation of nature, beyond the effects that it had on solely humans or from an only human vantage point. When we found this document, we thought it would be a fantastic opportunity to use its title and bring all the meanings that it had touched upon to our exhibition. What we understood from his thesis is that, in a way, those animals became us: the more productive-oriented our environment becomes, the more we need to protect ourselves from that.

TLmag: How can we protect ourselves then?

AR: That’s the tricky thing about the role and power of design. As you know, the market offers hundreds of gadgets, for example, to help us sleep better; like re-timer glasses, melatonin pills, weighted blankets, white noise’s devices, and a sea of app that help us to relax, disconnect, defining a sort of objectification of the self in accordance with social norms of health. We’re all exhausted because ‘being productive’ has become our only way of living. Instead of changing our behaviour and using less or turning off our phones, our behaviour has evolved to a point where our first response is to adopt the offers of the market as fast and disposable ‘solutions’. And these have been designed. Do we really want to live in a world in which we are entirely subjected to these conditions? And what’s more, those objects don’t address other species that are equally affected by the environment we are discussing.

TLmag: Could you walk me through the process of creating an exhibition about such a complex topic and the choice of featured works?

AR: From the beginning, it was clear to us that design should be presented as a critical practice that problematises conventional ways of inhabiting and experiencing the world founded on human control and exploitation of other bodies. So the works in the show present a layered, non-binary, picture of the multi-species relationship with darkness, imagined by designers, artists, researchers who set in motion critical responses to it.

For example, the first year students of the Social Design Masters programme at the Design Academy Eindhoven have presented an iPhone that performs a variety of applications and their push notifications, repetitive commands, gestures, and anxieties of our everyday experience. The audience sees the mobile phone invisibly browsing through a number of applications that are supposedly meant to restore our health and balance, but really that’s just another side of the same problem. Still surrounding this idea of the invisible but pervasive landscape of the digital, artist Danilo Correale travelled across New York, Manila, Bangalore and presented The Unsleep, an amazing photo-issue about outsourcing and night labour in call centres — a consequence of the need for 24/7 service in a western, capitalised world.

And last but not least, the documentarist and filmmaker Bregtje van der Haak displayed her collaborative project White Spots, which explores what is beyond the frontiers of the networked world to explore unwired landscapes, communities, and lifestyles, and questions the need to always be connected in one seamless, planetary “Tech-topia”. The work is also an application, which brings you to the so-called white spots dispersed onto the globe. It helps you to find the closest place where you cannot have a connection — and once arrived, you become invisible. We could even state that in some ways, invisibility becomes a quality in this world and a privilege.

TLmag: With the first step to restorativeness being to change people’s minds, could you tell me how has the reaction of the public has been?

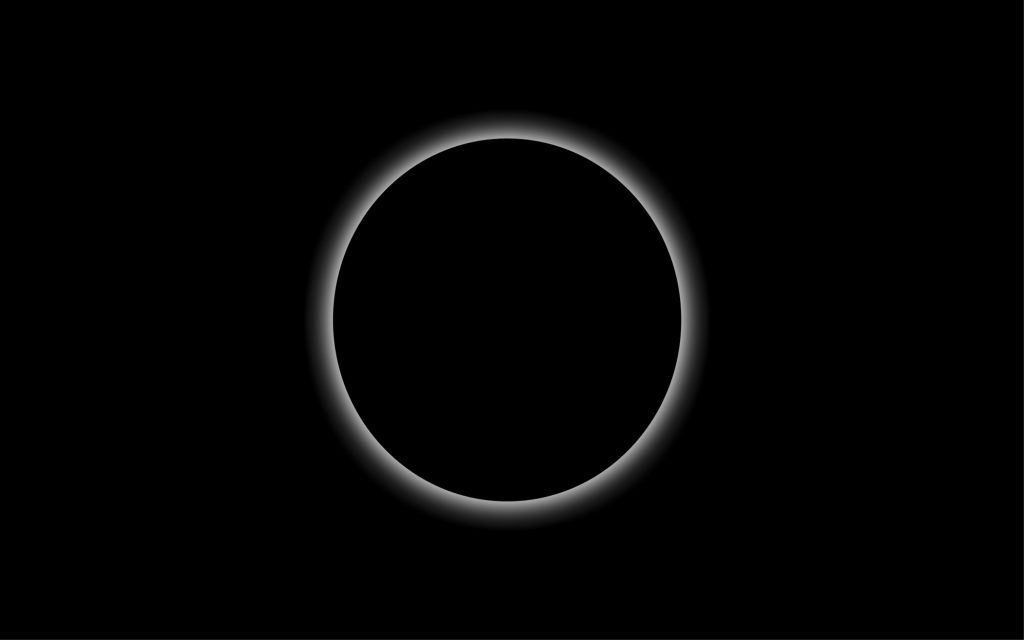

AR: The first response that we saw was when people entered the space: it’s a round and dark space, a so-called Panorama. Originally designed to create the illusion of a complete vision of the world, the spatial model of the panorama designed by Olivier Goethals for the exhibition becomes a medium that articulates a fragmented, incomplete representation of contemporary landscapes (like the automated, digital, infrastructural, cosmic ones).

It has to be interpreted also as a carrier and archive of research, illustrated and animated by Rudy Guedj, who have been amazing in ordering and translating all the information produced by the initial research. As visitors walked into this circular, almost black, space, they felt lost and unbalanced from the very first moment. Then, they become witness to moments of discovery and information on a specific condition of darkness — subsequently, dioramas, projections, or smooth screens reveal scenarios we don’t generally get, or choose, to see.

Other than that, there were a few other elements that we saw visitors responded quite well to: the iPhone kept being used or touched (even though that wasn’t allowed) and there were long lines of people wanting to try out Lucy McRae’s Compression Cradle. In this case, the designer enquired the intangibility of the pervasive effects of digital on our lives, that from one side gives us the impression that we are hyper-connected, and from the other make us just feel more lonely,

Willing to design a restorative experience, she created a “squeezing machine” that assists in altering the gene expression of oxytocin — a hormone released in the brain that’s responsible for building trust and couple bonding. It basically helps us humans restore those broken bonds not only within us and our bodies, but between individuals as well.

TLmag: After the Triennale, the presentation will travel to Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam in October later this year…

AR: The project doesn’t end here, it just started a conversation on possible relations or contradictions between light and dark, seeing and not seeing, their cultural value and how design can interact with all that by visualising challenges and inequalities as well as a not-yet recognised collective common good. HNI and the exhibition designers are now figuring out how the exhibition will be translated into their space. The structure will probably be very similar, but the idea behind is to maybe expand on some of the works, sometimes also through the public program that includes different typologies of events. As a curator, it will be interesting to see how some works can be differently translated into new outcomes and mediums, which underlines the power of knowledge’s production as an abstract machine that can be guided, set in motion and performed in a variety of modes.

Join Danilo Correale – contributor to ‘I See That I See What You Don’t See’ – on June 20, 2019, for his artist talk “Uchronia: Acts of Resistance Over a Spaceless Time”. With contributions by Erica Petrillo and moderated by Angela Rui.

Broken Nature will take place until September 1, 2019, and is curated by Paola Antonelli, senior curator of Architecture and Design and director of Research & Development at The Museum of Modern Art. ‘I See That I See What You Don’t See’ will travel to Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam in October 2019

https://triennale2019.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/en

Cover Photo: Panorama I See That I See What You Don’t See, Rudy Guedj, 2019. Photo: Daria Scagliola.