Fernando Laposse: Grassroots Design

For TLmag38: Origins, we spoke with Fernando Laposse about how his design practice has developed over the last several years in Mexico, where he works with local farmers using native plants such as corn and agave to create his contemporary design collections.

“It’s about using the example of this one village to see how much impact we can make in one location, with one community, and not water it down or dilute it to change the whole country or world. I think this is what change is going to be about. It’s a network of small initiatives rather than one massive solution fits all,” says Fernando Laposse about his design practice/ community-led business that is based between Mexico City, Puebla and London.

In 2015, Laposse, then living in London, went to Oaxaca on a 3-month residency, an experience that would take him on an eight year and counting journey into environmental activism, small farming, entrepreneurship and design. At the time he was in Oaxaca, painter and activist Francisco Toledo, who was based in city until his passing in 2019, and others, were pushing for a ban on GMOs in Mexico, an issue that Laposse could not help get involved with.

As humans we are constantly reinventing, trying to “advance” and speed things up, with the ironic twist that we never have enough time. In farming, the false allure of GMOs, powerful fertilizer’s and hybrid seeds for more efficient and “faster” farming has given way to soil erosion, monocultural produce and financial devastation for the small farmer. In Mexico, this was compounded by the 1994 NAFTA agreement, which along with corporate farming industry on the rise, nearly wiped out indigenous plants and biological diversity — particularly corn, a sacred plant for indigenous Mexican communities, if not the whole country. Interested in doing a project with heirloom corn, he began to think about the plant from a designer’s point of view: “What makes this corn special? It’s the colour — you cannot fake that. So, how do I celebrate this without taking the grain? The leaves,” he explains. The purples, pinks, creams and browns combined with the texture and size of the husk were perfect for a veneer, leading him to design Totomoxtle, a type of veneer that applies the techniques of wood marquetry to corn and which can be used on surfaces from furniture to walls.

When he was unable to find any native corn leaves at the central Oaxacan market, known as being one of the most traditional in Mexico, it was an eye opener at how serious the problem was, and he realised he would have to grow it himself if he wanted to pursue this idea. Laposse connected with Delfino Martinez, a long-time family friend in the village of Tonahuixtla, Puebla, an indigenous community that was suffering from the systemic problems that had crushed small farming.

“I see it as an economic problem… how can we make a small parallel economy that is not about the grain but will encourage farmers to continue planting? It is about design thinking but it is also thinking about economics, hand in hand, and really thinking system level,” says Laposse about the project behind Totomoxtle and his eventual collaboration with Delfino and the local community of Tonahuixtla.

Today, they are able to generate the same amount of income for the families with 1-square metre of Totomoxtle veneer than they would producing a whole hectare of grain. “I don’t own a square inch of this land, Laposse states, no one owns it. It’s communal”. They are not working with artisans either, but training people, mostly women, to learn the techniques required to make the product. “It’s about inventing our own techniques, our own crafts and our own practice” he says.

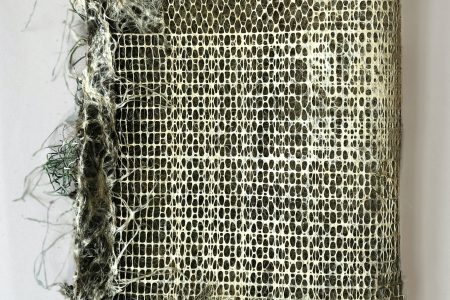

When he arrived in Tonahuixtla in 2015, the farmers were undertaking a new project of planting agaves to help regenerate the soil, which had been completely eroded. From this, Laposse began learning about the fibers of the agave plant that make sisal, once a booming industry in the 17th–18th centuries in the Yucatan. The hairs of the sisal plant reminded him of horse hair and “it made sense to design something animalistic. I let the material determine the form” he notes about his sisal collection, which includes the Pink Beasts and The Dogs series, which mimic animals and the cocooning form of animal dwellings.

“I don’t think it is accurate to say that I am looking at the past,” he says. According to recent records, about 15% of the population of Mexico is indigenous, which is about 20 million people. “That is a lot of people, and a lot of people who are still planting in this same way –so it’s not looking to the past – but at what they are still doing.” This distinction is critical; Something that has been done for thousands of years, yes it has history and heritage, but it’s still alive, and it is essential to understand that and learn from it if we are going to find solutions for the future of farming and the climate crisis.

Laposse and his studio are regularly experimenting with new materials connected to the land. As he says, “It’s about talking about how the global market can have crazy consequences on very localized communities. This is the essence of my work with every project that I do.”

@fernandolaposse

@sarahmyerscough