Aimé Mpane – Between shadow and light: sculpting and painting humanity

The fine arts have no secrets for Aimé Mpane, a humanist with a message, the son of a sculptor and cabinet-maker, and a sculptor and painter himself.

The fine arts have no secrets for Aimé Mpane, a humanist with a message, the son of a sculptor and cabinet-maker, and a sculptor and painter himself. After studying at the Fine Arts Academy of Kinshasa, where he focused on painting, Mpane continued to La Cambre National School of Visual Arts, from which he graduated in 2000. The context in which Mpane lives—he resides in Belgium but remains deeply attached to his native Congo—drives him to create works that are at once critical, intellectual and profoundly humane. He addresses the major existential and material problems of our society without abandoning optimism and his interest for the human condition.

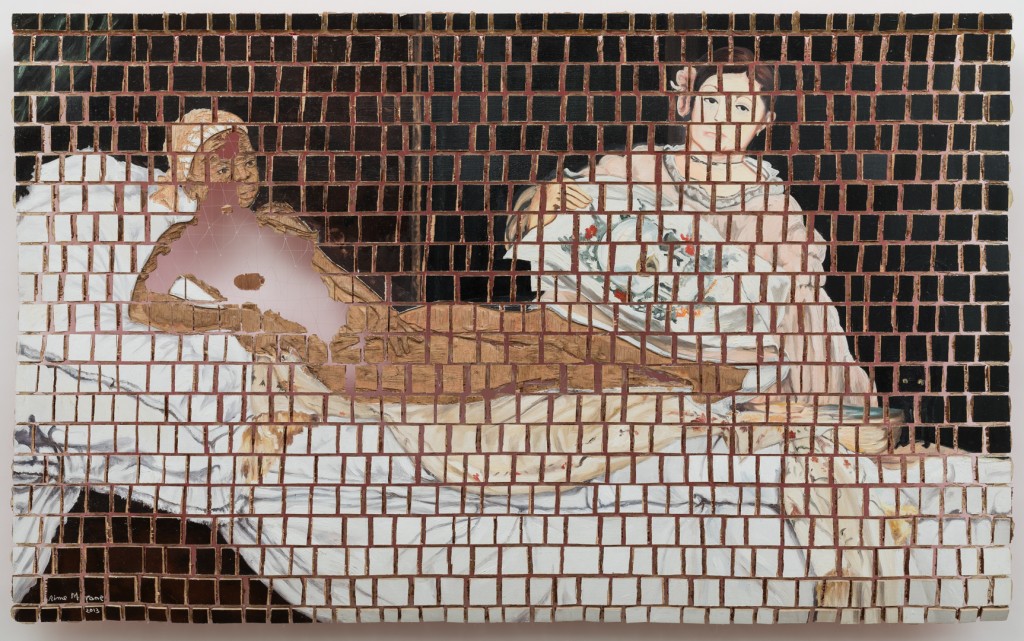

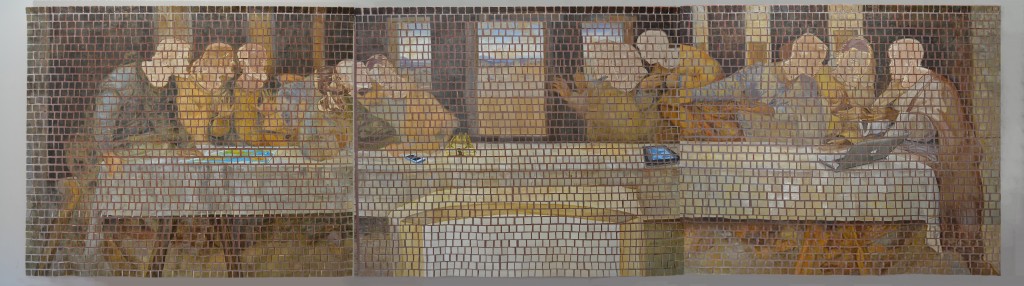

This humanist quest is present throughout his artistic oeuvre, in which Mpane associates objects and contemporary art and contextualises them in his installations using a universal language. Leaving behind the stigmas of the African continent to enter a territory of multiculturalism is at the heart of his artistic approach and his narrative. When I entered his Anderlecht studio, I found myself face to face with The Last Supper, revisited—not in Leonardo da Vinci’s original medium of tempera on gesso, but in Mpane’s unique mosaic-on-fishing-net technique. In some ways similar to a codex or a rolled parchment, this monumental pictorial work echoes his hollowed-out planar sculptures while bringing in the idea of a canvas painted by a grand master. Wending between academic painting and sculpture, Mpane’s path is unique within the field of fine arts. From matchsticks to cut wood pieces glued together, his materials may seem aligned with the ‘arte povera’ movement but are transcended by colour, whether on the reverse side for his mosaic-paintings, on both sides for his double-sided portraits, or in the space between two openface walls playing with emptiness and fullness. ‘I like using the colour red inside sculptures to define the invisible’, says Mpane. His large, reconstituted boards of small, glued wood pieces attached to a woven framework can be rolled up like carpets for travel. In this way, following a stint at a New York exhibition, Mpane’s Olympia will be displayed next to Manet’s painting at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. The same is true for his Last Supper, inspired by da Vinci’s painting preserved at the Santa Maria delle Grazie convent in Milan, which he designed at its current home, reinterpreting the original and incorporating new figures and his own story. ‘I break things down to put them back together. I didn’t want to choose the form of a painting, preferring instead a planar surface. I like brick walls and reproduce them as ‘trompe l’œil’, creating optical illusions. I had the idea of reinventing the mosaic, a technique dating back to antiquity which existed across civilisations, when I was looking at the wall made of small bricks that I stand across from in my studio in Brussels. I made the mosaic malleable, so it could be folded up and transported in a normal suitcase. It is light in terms of its structure, but it bears a cosmic message’, said Mpane.

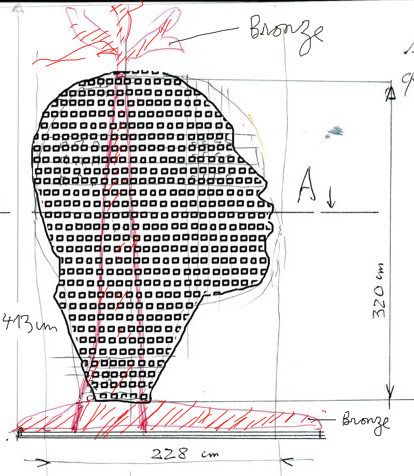

He continued, ‘When the Tervuren Museum sent out a call for proposals for a monumental sculpture to celebrate its renovation and reopening at the end of this year, I designed a project that lies outside of the context of the Congo and decolonisation. I call it Congo, Nouveau Souffle (Congo, New Breath). I wanted to share a positive image of my country, and I played on a vision of contrasts. The rotunda [of the museum, where the sculpture will be displayed] inspired my use of transparency by evoking memory and light. The portrait of Leopold II and the crown of palms that surrounds him gave me the idea of a large, budding plant that reaches toward hope and clarity. A face sits at the centre of the sculpture. Traces of the past live on, but without classical references.’ With this monumental work inspired by current airport sculptures, Mpane has used a great economy of means, despite the colossal implementation work involved. ‘I don’t make the wood three-dimensional using an already rounded part. I cut the contours from a board to create a human form, tracing the profile with rounded shapes. From each side of the two corridors, viewers can see the sculpture from afar. It’s like seeing a tree. The bronze flows between the walls all the way to the ground to embody the negative energy leaving the human being, while the crown of branches symbolises the human journey toward light. The transparency of the sculpture, which is painted red inside, lends it light, majesty and symbolism.’

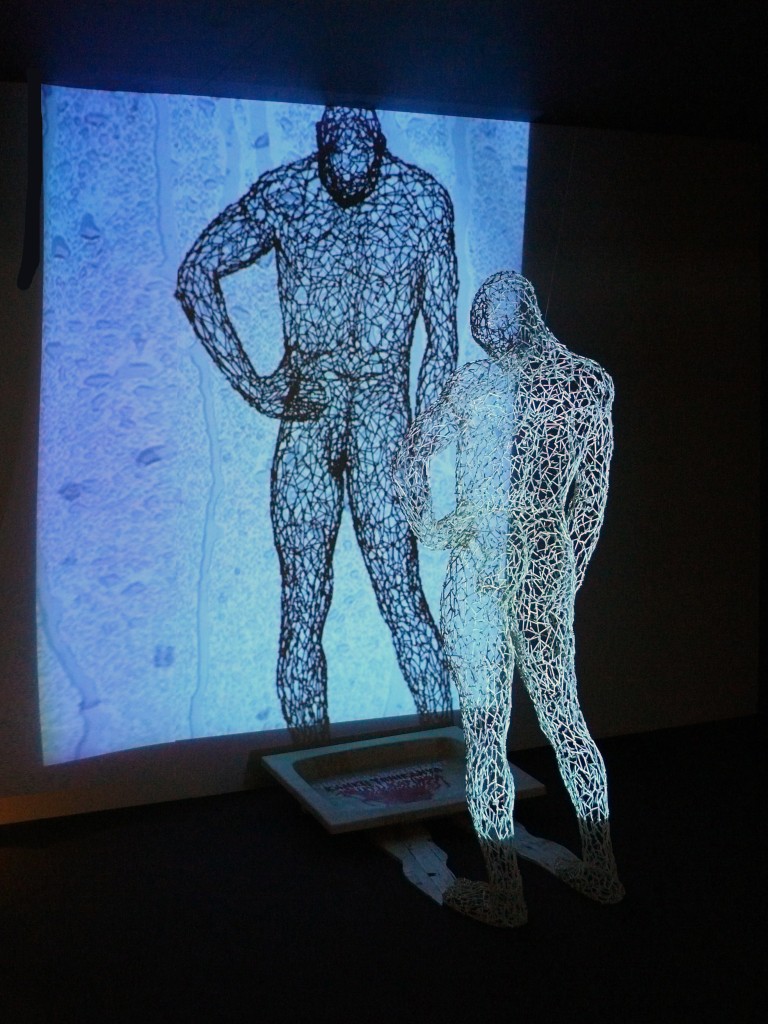

Having recently installed one of his sculptures in front of the entry to the Belgian embassy in Kinshasa, Mpane explained the work in terms of human relationships. ‘My concept was of two men meeting, a white man and a black man. Since the building’s façade is largely transparent, the hollowed wooden sculpture stands out even more, with the sun’s rays travelling through it. In the installation, two men greet each other: the Congolese man sets down his briefcase, and the Belgian man visiting the embassy carries his briefcase. You can see the work from the highway. Its message is clear, but if you want to look deeper, of course you can find plenty of other underlying messages.’

Mpane often works in public spaces on commission as well as in museums and art and ethnographic collections. One of his recent exhibitions, J’ai oublié de rêver (I Forgot to Dream) took place last spring at the Ianchelevici Museum in La Louvière, where his sculptures and installations were displayed alongside those of the great Moldovan sculptor Idel Ianchelevici. Mpane explained his strategy for exhibitions, saying, ‘My approach is to work within a network separate from that of African art galleries and curators. For example, I work with the Haines Gallery in San Francisco and Nomad Gallery in Brussels. Doing so means that American and European curators take an interest in my work.’

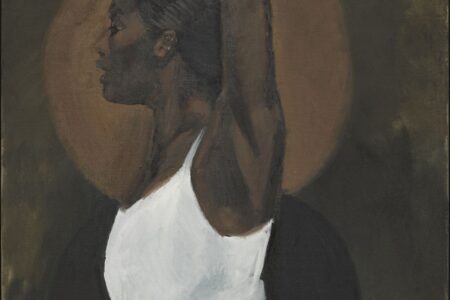

The artist likes to revisit objects, which lie at the source of his work, in a play of cultures, using wood or matches. He created his own dictionary of synonyms for the word ‘peace’ in the form of a playful collection of objects, relating to each other with expressive tension. ‘I’ve already created 20 of them and have 20 more to make’, he said. Similar relationships can be seen in his masks inspired by those of the Pende in the Congo. ‘I wanted to create a series of sculpted portraits representing Pende women subjected to prostitution to mirror some of Picasso’s portraits, including the Demoiselles d’Avignon. The object interacts with the painting, becoming double-sided—hollow inside and in relief on the outside, as though memory were getting lost and reappearing on the surface’, Mpane said. This approach also helps him question the way that African objects are displayed in museums. He took this interrogation to the Brooklyn Museum in one of his installations in dialogue with the ethnographic collection.

Similar to his masks, Mpane has also created painted wooden portraits of Pygmies’ faces. He explained, ‘Triplex wood evokes human skin; I use it in a 31 x 32 cm format. The tool I use to sculpt the wood, similar to a small hatchet, works like a woodpecker that pecks a tree and eats it. The system is symbolic: carving, shaping and working on pieces of a single size. I like acting on a living thing and feeling that it is alive.’

From his sculpted wooden tyres upon which he engraved the word ‘Democracy’ to his European flag with a hole in the centre, adorned with yellow daffodils like the stars of the EU, Mpane sees the world with a critical gaze. Of his large tableau Les portes de la vie (The Doors of Life), which was seven-and-a-half metres long when he left La Cambre, nothing remains but a picture on his mobile phone. Fortunately, TLmag has found the traces of a few of his many canvases among the collector Vincent Coppée’s acquisitions in Tangier. More adventures with Aimé Mpane’s work are still to come.