Ethiopia’s Omo Valley through the lens of Alex Franco

For thousands of years, the Omo Valley, in Southern Ethiopia, has been a place of cultural and ethnic encounter. The various peoples who’ve lived and migrated across the basin – the ochre-skinned Hamer, the scarified Karo and the lip-plated Suri and Mursi, to name a few – are pastoralists or agro-pastoralists, who have cultivated the land and reared cattle there for millennia. The ancient cultures that arose in the Omo river’s fertile valley date as far back as the Pleistocene era. Today, the men and women of the Omo Valley are known for, and studied for, their cultural diversity, and the area is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Tourism is steadily rising, and the colourful, proud people are photographed profusely by documentary and amateur photographers alike.

One photographer stands out: Alex Franco, a Barcelona-born and London-based autodidact with experience in both fashion and documentary photography.Having moved to London 12 years ago, after feeling that “Barcelona had nothing more to offer me at that point in my life,” Franco immersed himself in the English capital. “London allowed me to discover more about myself, other people and my craft, and taught me to connect to different cultures and subcultures,” he says. “You experience a constant sense of renewal personally and professionally.”

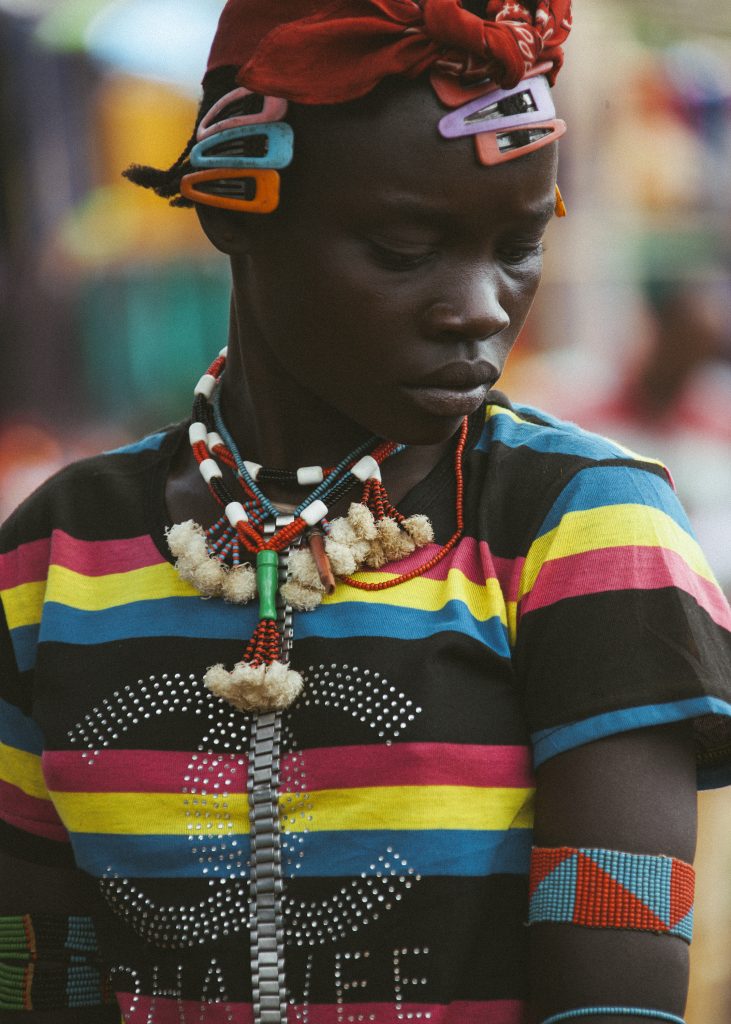

Growing up in Spain means he “adopted a fairly open-minded and liberated mind-set,” Franco adds. “I feel that I have an appreciation for this sensibility to appreciate while exploring the curiosities that make life interesting and meaningful.”Through a good friend of his, who’s from Djibouti but was raised in Ethiopia, Franco ended up visiting the Omo Valley in 2013. “Honestly, I had no expectations,” he admits. “I had a very clear feeling that all I wanted to do was to get to know these communities and learn from them. There is definitely a stereotype of what these communities are about, but I do not believe it is entirely accurate.” It’s true that in many instances, especially with tourists, there is no pretence at social interaction when they visit the villages of the Omo Valley. They come, they click, and they leave with a snapshot that reflects the way they, themselves wanted to view the people whose culture they ostensibly came to appreciate. Franco, on the other hand, was determined to try to live the Omo Valley peoples’ experience from as close as possible. “With the Hamer tribe, I was very lucky to be very close to one family,” he explains. “That gave me a really close insight of their everyday life, how they made their clothes, cooked their food, or interacted with other communities. I spent day and night with them in their huts – it was truly special. I was also fortunate enough to be invited to very personal ceremonies within tribes, that not many ‘outsiders’ would get a chance to experience.” This feeling of closeness comes across strongly in Franco’s imagery. The confident gaze of his subjects, the detailed close-ups of scarified skin or garment details, the almost unsuspecting feel of some of the poses, are elements that imbue the photographs with a feeling of proximity and mutual respect.“I loved it there,” exclaims Franco about his experience of living among the Hamer tribe. “Everyday would be a new adventure, something new to learn, to photograph, to do.”When it comes to how best to read Franco’s images, there’s an interesting tension to take into account. A Western gaze is apt to view these images with an aestheticizing angle – imposing certain standards of style or beauty onto these individuals, who, very often are simply making do with the garments dumped on them, leftovers as these pieces of clothing are from the West.

Franco agrees it’s a conclusion made from a Western perspective. The aesthetic use of these pieces clothing, like jeans, t-shirts and branded garments, is not a part of their traditional culture – yet, Franco feels that it’s really different ‘case by case, for each individual. Some are attracted to practicality, while others are attracted to certain pieces out of a sense of personal style.’ He explains: ‘It could be said that they don’t have a choice in what is given to them, but they can choose inside their options. The point is – we like to define who we are with what we have and the way we carry ourselves will show that.’ What it comes down to is the universality of self-expression, with whatever means people have, with the restrictions that are present.

The beauty of Franco’s photographs, and the reason why one has the feeling one can keep looking at them endlessly, has to do with that tension between the very valuable elements of the diverse cultures of the tribes of the Omo Valley, and the out-of-place looking elements of Western garb, which, they somehow make to look completely natural, and not like an oxymoron at all.Every element fits and inspires a sense of awe, which is testament to the inherent sense of self, eye for composition and personal pride. The members of these various tribes have made such an impact with what’s very simply something we all do in the morning – get dressed. “I don’t think there is a country in Africa that can be compared with Ethiopia,” says Franco. You can make that: “any country in the world.”