Generation Next: The New Wave of Czech Art Glass

Contemporary Czech glass art has created a major imprint in the world, and today is pulsating, full of life, and a vibrant component of the global scene. This new generation of glass artists is defined by a sense of artistic restlessness – a generation searching and experimenting.

Context and Genesis

After the Velvet Revolution of 1989, Czechoslovakia began the process of transforming from an authoritarian communist regime into a democratic state. The new-found freedoms that emerged not only brought about a social and economic transformation, but also a kind of mental revolution. Overnight, what had been the cultural mainstream became the “old times”, and alternative approaches became the norm – an inversion that turned black to white and white to black. However, in the world of Czech art glass, the 1990s were in fact characterised by conservative approaches, dominated by cast glass.

There are many reasons why this was the case. Despite the fact that the scale of glassmaking techniques in Czechoslovakia was very broad, only cast glass can undoubtedly be categorised as a major home-grown innovation. This was primarily due to the abstract works of Czech glass artists Stanislav Libenský (1921-2002) and Jaroslava Brychtová (born 1924), which gained the recognition of critics and engendered the interest of collectors around the world. Libenský was also a long-serving university teacher at Prague’s Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague (UMPRUM – from 1963-1987) as well as a highly-sought lecturer abroad. In his wake, he left behind a large number of progenitors who followed in his footsteps. And so it is little wonder that after the fall of the Iron Curtain, demand for cast glass sculptures grew significantly. Alas, this growth in both artists and the numbers of works they produced – naturally not only in the Czech Republic (the independent country that emerged after the break-up of Czechoslovakia in 1993) – also led to an exhaustion of potential artistic approaches. Consequently, what was once a symbol of technological and artistic innovation instead became rather run-of-the-mill; in many cases artistic pioneering was replaced with a bet on certainty, and the production of imitation works and replicas.

With the turn of the century, the so-called “Libenský School”, incorporating artists born from the 1940s-60s, began to gradually lose its dominant position. This was due to the emergence of notable new aesthetic directions, as well as the rise of so-called “artistic” or “studio” design movements that aspired to shake-up the existing barriers between the fine arts and applied arts. Vladimír Kopecký (born 1931) played a formative and educational role in this through the UMPRUM glass studio, which he led from 1990-2008.

Kopecký, an artist and theorist of so-called “ugly glass”, serves as a symbol of an entirely different form of glass art – not formally classical, but rather essentially anarchistic. As a result of the new opportunities for cultivating contacts abroad as well as the free access to information, his students both absorbed and mirrored the global glass art of the times.

Additionally, from 1992-1999, UMPRUM also operated the inspiring Glass in Architecture studio, led by Marian Karel (born 1944). This studio promoted artistic purity, well-planned details, combining materials to make use of their mutual interaction.

More and more glass studios gradually emerged at universities in Ústí nad Labem and Zlín, which led to an increase in teaching staff offering their own visions, as well as an increase in graduates. All of this combined to lay the groundwork for the emergence of the generation born in the 1970s and 80s – Generation Next.

Generation Next

If this generation can be defined by a single characteristic, it is openness. Generation Next is united not by any single aesthetic viewpoint, but rather by its sheer numbers. Members do not seek out artistic meaning in tandem, but rather each member undertakes their own search, strictly adhering to principles of individualism and a distrust of established rules and approaches. Those born in 1970s Czechoslovakia also greatly value their freedom, because their experiences of the former communist regime came at a formative moment in their adolescence. For them, freedom is not to be taken for granted, but is rather a privilege in which they dared not believe. Perhaps for those reasons too, this generation is defined by a sense of artistic restlessness – a generation searching and experimenting.

These artists put to use a very wide range of techniques and decorations in their works. Most commonly, they undertake molten glass approaches, combining techniques, using fusing and other innovations, as well as traditional cast glass sculpting methods. They also enjoy combining glass with other materials – either to emphasise its optical-aesthetic properties, or, conversely, to downplay them. They regularly utilise the entire spectrum of cold decorative techniques – cutting, engraving, painting, etching, sanding or laminating.

The glass artists of Generation Next can be divided – in terms of their creative sensibilities – into sculptors, painters, architects and inventors. The sculptors form the largest group, working with various forms and using various techniques to search out the inherent creative limits and opportunities of their field. This group includes the coarsely cut and laminated works of Anna Polanská (born 1973); the meaningful cast and blown glass makefasts of Martin Hlubuček (born 1974); the geometrical pieces that feature unexpected details of Ondřej Strnadel (born 1979); and the pioneering “inside the bubble” glass sculpting techniques yielding realistic portraits of Martin Janecký (born 1980).

Also worth a mention for his equally effective cut vases is Libor Doležal (born 1977); the diverse techniques of Bohumil Eliáš, Jr. (born 1980) that yield distinctively visually attractive works; and the playful cast glass works of Zuzana Kynčlová (born 1985).

An emphasis on decor, external and internal structures, surface contrasting, and spiritual landscapes – these are the attributes of the painters. The glass paintings of Lada Semecká (born 1973) offer a powerful brooding quality; the abstractly dynamic painted works of Josef Divín (born 1982) are also worthy of attention; as well as the lyrical engravings of Pavlína Čambalová (born 1986). The glass compositions of Song Mi Kim (born 1972) offer a strong sense of storytelling; add to that the provocative works of Jaroslav Koléšek (born 1974); the imaginative layered glass landscapes of Kateřina Krausová (born 1978); and the disquietingly raw glass art objects of Irena Czepcová (born 1986).

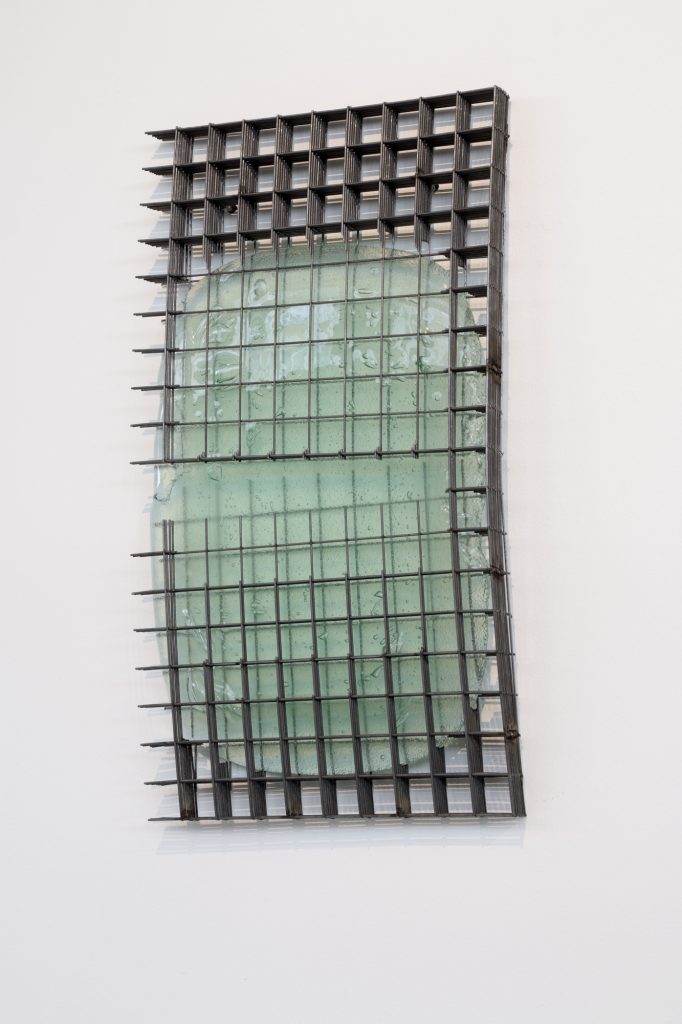

Architects are the next distinctive group, creating their own constructions, changing spaces in their own image, working with materials in a refined manner, creating transparency, translucence, reflections, both obvious and concealed. Petr Stanický (born 1975) is undoubtedly part of this group, with his numerous architectural interventions; also the exquisite sense of form found in the works of Michal Motyčka (born 1975); or the geometric cut and laminated glass art works of Ingrid Račková (born 1975) and David Suchopárek (born 1973).

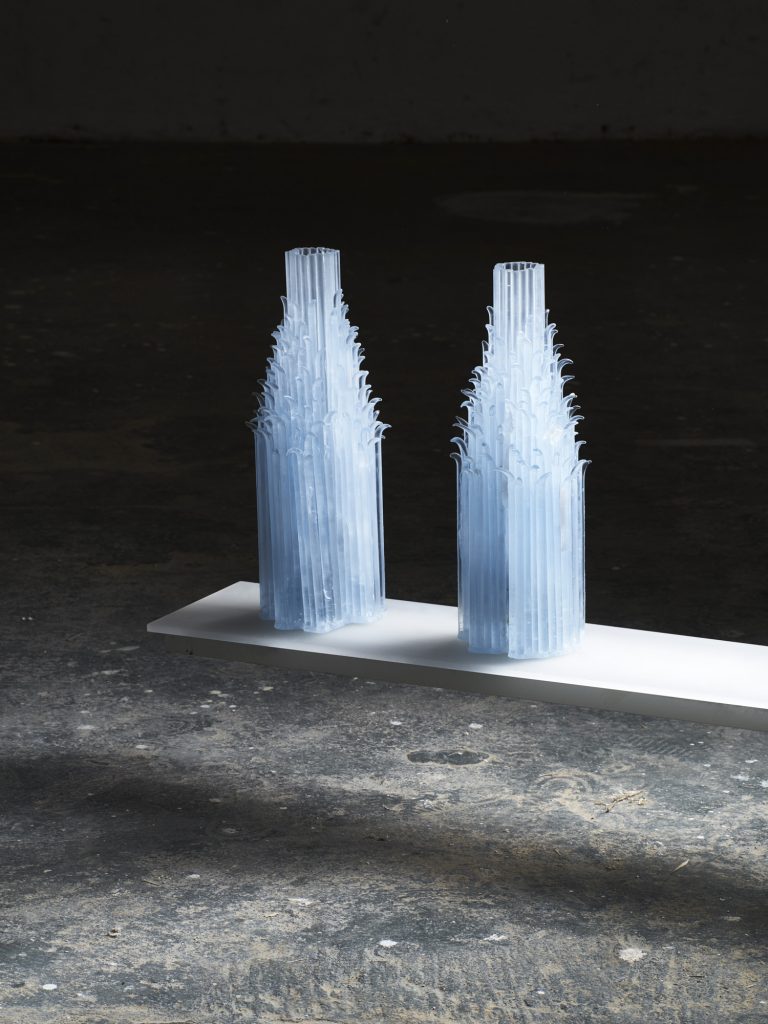

In terms of the 1970s and 80s generation, the inventors represent a very distinctive group, experimenting both with glass as a material, and also with the possibilities of its forming and decoration, as well as with overall artistic meaning. Klára Horáčková’s (born 1980) glass tubes are constructed into distinctive geo-formations; Luba Bakičová (born 1985) presents compact sculptural forms made from fire-resistant materials and glass; Michaela Spružinová (born 1983) transforms recycled glass into provocative artefacts; and Zuzana Kubelková (born 1987) offers organic amorphous compositions made from melted glass textiles. Milan Krajíček (born 1977) and Václav Řezáč (born 1977) have also taken particularly creative approaches to glass art. The former has developed his own technological approach, which yields unique decorative art objects of traditional cut glass. The latter turns the glassmaking lexicon on its head, disturbing cut glass surfaces with molten glass. Finally, Stanislav Müller’s (born 1971) interactive “Mirrorman” also turns on its head existing preconceptions about glassmaking.

Today, Czech glass artists born in the 1970s and 80s – a generation that we can without hyperbole label as the New Wave of Czech Art Glass – regularly display their works in galleries and museums. Their works have become an integral part of public and private collections, and significantly influence the domestic artistic scene through finding success abroad. Lada Semecká, Stanislav Müller and Václav Řezáč have taught at the Toyama City Institute of Glass Art in Japan; Martin Janecký and Pavlína Čambalová have also become highly-sought teachers; and Petr Stanický is realising his interventions in established artistic institutions around the world. Indeed, their functions as teachers are equally important to the output produced by these pioneering glass artists. Stanický heads the glass studio at Zlín University; Spružinová works as an expert assistant at the same institution; Horáčková serves as an expert assistant in glassmaking at UMPRUM; for many years, Bakičová worked as an expert assistant at a glass studio in Ústí nad Labem; while Divín, Krajíček, Kynčlová, Polanská and Strnadel are offering their services at glassmaking high schools.

Prague’s Galerie Kuzebauch has consistently sought to highlight the glass art works and artists of Generation Next. Since its founding in 2013, the gallery has emphasised showcasing the varied approaches to glassmaking that are certainly highly evident among this group of artists. The gallery has also spent years following the artistic development of its members, so as to best present the contemporary face of Czech glassmaking both at home and abroad.

In terms of both technology and aesthetics, contemporary Czech glass art has created a major imprint in the world. It has endured its academic phase, and is today again pulsating, full of life, and a vibrant component of the global scene. The restless Generation Next certainly deserves considerable credit for shifting Czech glass art from its former inward-looking sensibilities, and instead spreading its wings far and wide.

PhDr. Petr Nový is curator of Galerie Kuzebauch, Prague.