Germaine Kruip: Disappearing Act

With a distinctive geometric language, Germaine Kruip plays with phenomena such as light, shadow, time and sound to create moments where the act of looking becomes a collective reflection.

Germaine Kruip creates art that is a kind of disappearing act. It does not point towards itself, but to something else: a closer observation of the natural world, a prompt to shift perspective, or an invitation to relate differently to the environment in which we find ourselves. The artist creates deceptively simple sculptures and performance pieces and has recently joined Axel Vervoordt Gallery. With a distinctive geometric language, Kruip plays with phenomena such as light, shadow, time and sound to create moments where the act of looking becomes a collective reflection. TLmag speaks with the artist about the links between theatre and the visual arts, mixing mediums, and the beauty of the collective gaze.

TLmag: What was it that formed your interest or focus on working with phenomena?

Germaine Kruip (GK): My background is in scenography, and my practice began in theatre. When I was working in theatre, I had the realisation that everything we look at is so layered, and that in looking at something we create what we see. Studying theatre helped a lot in realising the role of the public in this process, because the architecture in which you are working is always from the perspective of the audience. I think this helped me to be less focused on being an artist, and more on thinking about what it means to be a viewer. It’s also why I enjoy working in the realm of phenomena – it’s a question of interpretation. For example, I have an enormous fascination for light. By changing light you can add a sense of time to what you see, or you can change your subject so that you’re forced to start reading it differently. It influences how you see something, and how you interpret what you’re seeing. This process of interpretation and the stories created by the viewer is something that interests me a lot; we all have different perspectives. I like that openness.

TLmag: How do you view the relationship between art and theatre? How does this play out in your work?

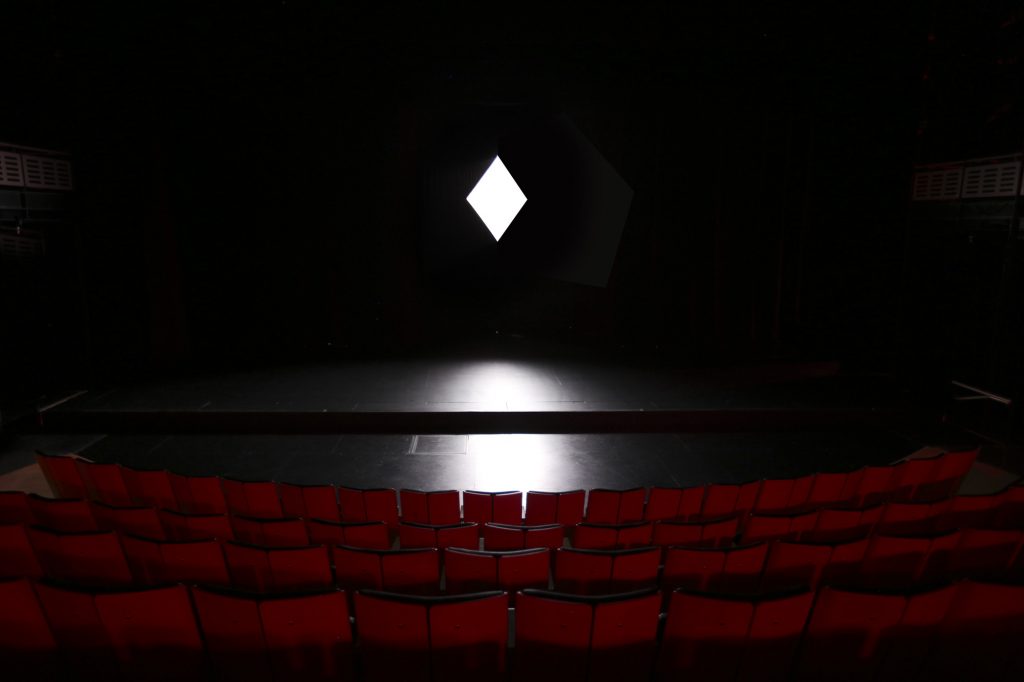

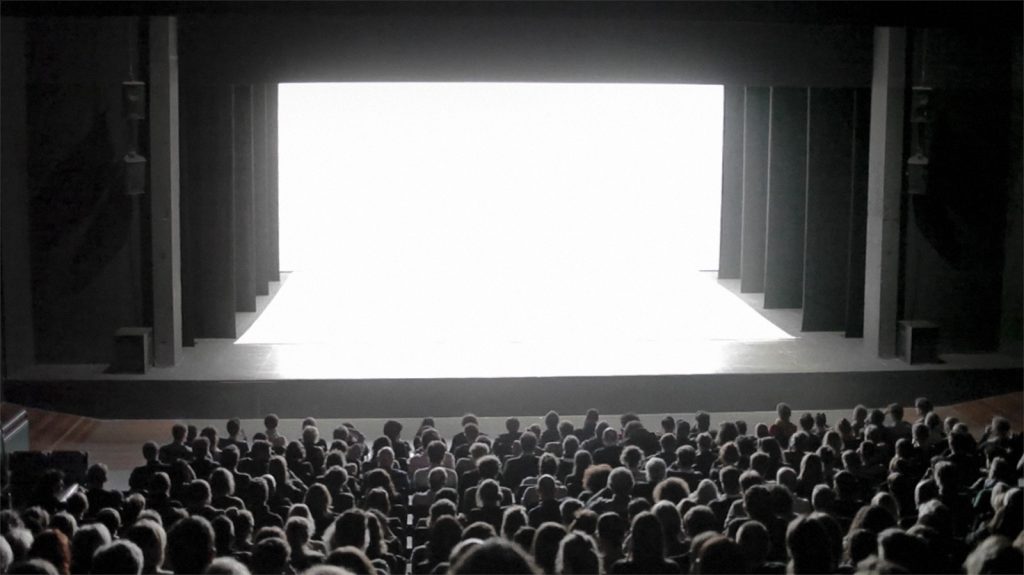

GK: In theatre we often work in a very strict framework or formula, so in 2000 I moved away from this because I felt I could explore and experiment further in the realm of the visual arts. But as an artist, I still worked with ideas such as staging, light, sound, and surroundings. I was always creating and thinking as a scenographer, like a dramaturge, but in the context of a museum. I would ask myself about how the visitors enter a space, how they experience this space they just entered, and what the context is. At the outset of each project I would write a mental script that took all those aspects into account and view them as material. When I did a residency at EMPAC in 2014, and made the work A Possibility of an Abstraction I came full circle and really understood how to use the architecture, stage, and timeframe of a given theatre space. When you come to a museum, you’re usually experiencing and seeing things in your own time. In returning to theatre after 14 years, I really appreciated the time and focus that it gives you, as well as the beauty of a shared experience and a collective gaze. It’s dedicated time and space to fully experience something. That act of slowing down is how I think theatre can enrich our experience of the visual arts.

TLmag: You often work with geometric shapes. Where does this interest come from?

GK: It started with an early fascination with De Stijl. I am Dutch but was raised in Belgium, and I think that looking at De Stijl was also a little bit like looking at part of my identity. They had these very simple aesthetics, but with a whole social idea behind them. I also love how each shape is given its own meaning without actually expressing it in itself. I made a work called ‘A Square Spoken’, in which I researched how we have interpreted the square throughout history. The work is a one on one lecture walk with quotes from different philosophers, scientists and artists that expose how the meaning of a simple shape changes over time. A shape in itself has no “true” meaning—only the meaning we project onto it. If you look at a square, you look into an emptiness which allows you to interpret and reflect the historical point of view that you’ve always been thinking and seeing from. By documenting the square through quotes, I hope to come closer to how our collective memory is projected into what we see. It is like a window to the zeitgeist.

TLmag: Your work often sits within the mediums of sculpture and phenomena. How do you activate these through performance?

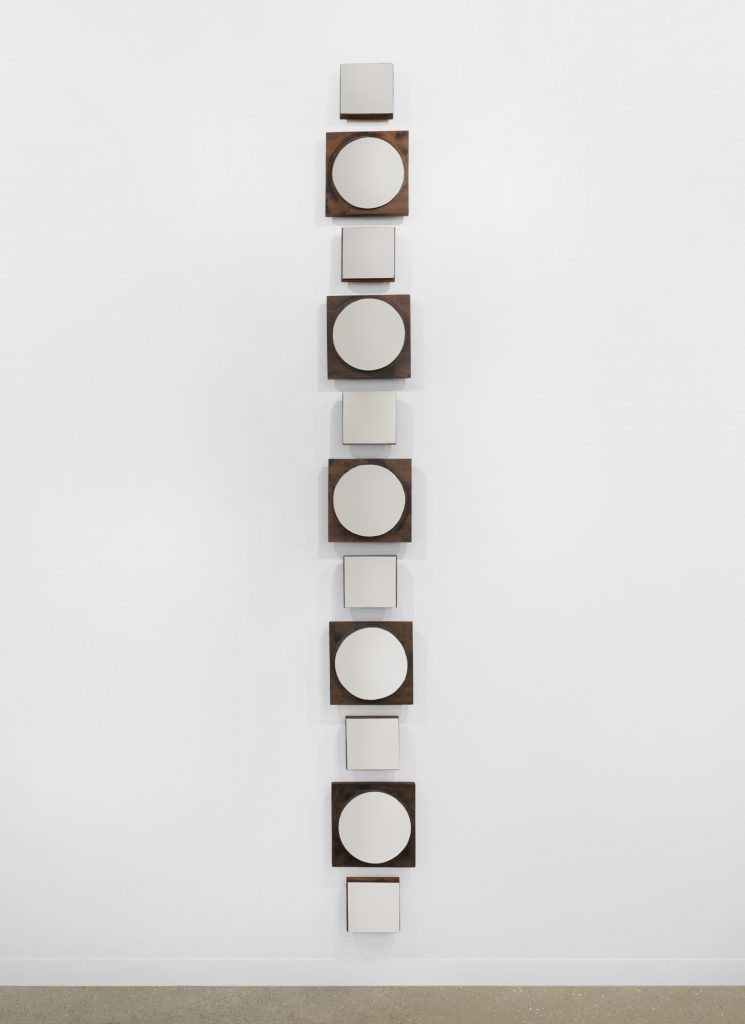

GK: There’s no strategy behind it, it always grows out of intuition. I find it difficult to explain, because I feel, for instance, that works such as my Kannadi pieces are sculptural works, but I also see them as performances. A Kannadi is a handmade metal-alloy mirror made in Kerala, India, by craftsmen with whom I started a dialogue many years ago. The mirror is attached to wood with wax, and in the last phase of the process they hand-polish the mirror. You see all the traces of the process around the wood, and it is important for me to leave them there. The grip where they hold the base to polish it is also what I use to hang it on the wall. It becomes a frame, and there’s a performative element in the sculpture. In contrast to that, ‘A Possibility of Abstraction’ is literally a live performance on stage. I call it a theatre work, but it’s also a sculpture. It’s a 55 minute art piece. So my work always has a sense of having a foot in one medium, and the other foot in another.

On the 20th of October, I will premiere my project Resonance at Antwerp Central Station during the EUROPALIA Festival. For this I have developed five monumental brass beams that act like percussion instruments. These instruments were forged and hand-tuned by renowned instrument-maker Thein Brass in Germany. I like to call them sonic or performative sculptures. The beams will be installed along the balcony of the entrance hall and will be activated by five percussionists during scheduled performances. In this sense, the project lies at the intersection of music and the visual arts. I love it when there is a crossover between mediums. I think a lot about the idea of the frame – where work begins and ends, and where a medium begins and ends too.

TLmag: I’m curious about the title of the A Possibility of Abstraction series, as it presents itself less as an investigation, and more as a hypothesis. As an artist, how do you approach this openness? Does it ever feel like a kind of calculated risk?

GK: A Possibility of Abstraction is very much about how you create what you see. It’s hidden in the title; you’re interpreting, and you will always give meaning to what you see, even if it’s abstract. Even if no explanation or framework is presented to you, you will always apply a logic. The work becomes like a mirror to your own view or thoughts, and brings an awareness that you are an activator: you have a voice and give meaning to the world around you. I also want the audience to feel that this possibility is not an emptiness. It’s not blank. It’s very full, and it works as an invitation to act, or to be. As an artist, you can’t calculate, or measure something like this. There’s always a moment where you just have to let go. I leave a lot open in my work, and there’s a simplicity to it, but to reach that simplicity requires enormous process and much more investment than people ever see. I also don’t want people to see my struggles, because my work is not about me as an artist. Actually, my aim is that when you see my work you forget about me and think about yourself. My handwriting has to disappear somehow. It’s not about entertaining, and it’s not about the audience finding the right answer or a key. I’m not holding a key. I’m just creating a moment.

TLmag: For every artist there’s a moment where the work passes out of their hands and into the world, and past that point you can only control so much of how people interpret or respond to something. I find the fact that you play with this specific moment really interesting.

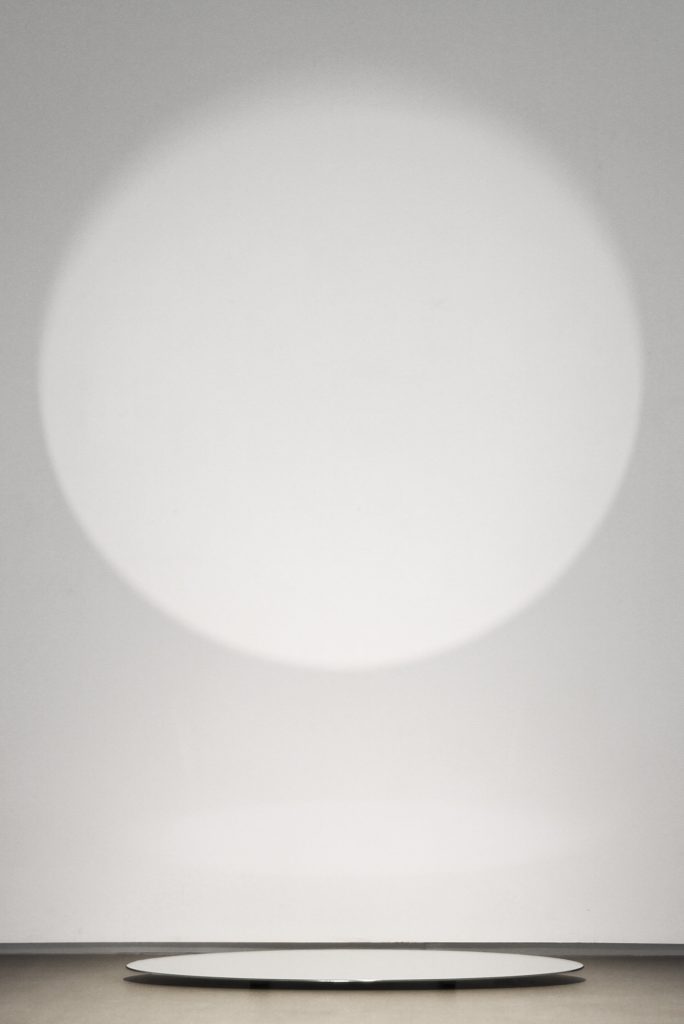

GK: I remember when I was at the Rijksakademie, one of the mentors came into my studio and he told me that anyone could make the work I was creating. In his mind this was a critique, but actually it was exactly what I wanted. Sometimes there’s a simplicity to the work that everyone can identify with. For instance, I have a piece called Untitled Circle, in which I place an elliptical mirror on the ground. When I put a spotlight on it, it reflects a perfect circle. This particular piece happened by coincidence. I was working with a mirror ellipse in my studio and had a light installed there, and as I was carrying the ellipse from one point to another I suddenly saw the reflection of a perfect circle on the wall. Something like this could happen to anybody, but I chose to stay with that moment, and the work was then in recreating it for others to experience. It became a journey of finding the exact angle and distance, which lamp, what kind of light, and so on. There are many, many details to consider in the process of finalising a piece like this, so that in the end it resembles that first simple moment. A phenomenon like this is owned by everybody; it’s not mine, but my role as an artist brings a kind of freshness to this way of working or observing, where I can say “look at this, look what happens”.