Hanneke de Leeuw Tells the Future History of Tableware

The designer behind Fabrique Publique has found new uses for discarded ceramics. The results will be on display in this year’s edition of Ventura Future.

In one of the rooms of Cor Unum factory in ’s-Hertogenbosch, a worker is careful to leave the border imperfections that form outside the mould of one of Sofie Boonman’s porcelain vases. “She likes it that way,” she says, referring to the designer. Behind her, a young woman puts a sponge to a row of plates from Charlotte Landsheer’s Reglaze series, made from reprocessed glaze waste. A few metres away, a storage closet holds the oddly large moulds for Maarten Baas’ oddly large Fat Vase for a Fat Plant.

So it’s no wonder that, in an environment that thrives on finding joy in imperfections, in seeing gold where other see waste and where expected proportions are easily subverted, Hanneke de Leeuw feels right at home. The designer, set on a station in the same room, has been working on turning broken and discarded ceramics from Cor Unum’s production into a new tableware collection.

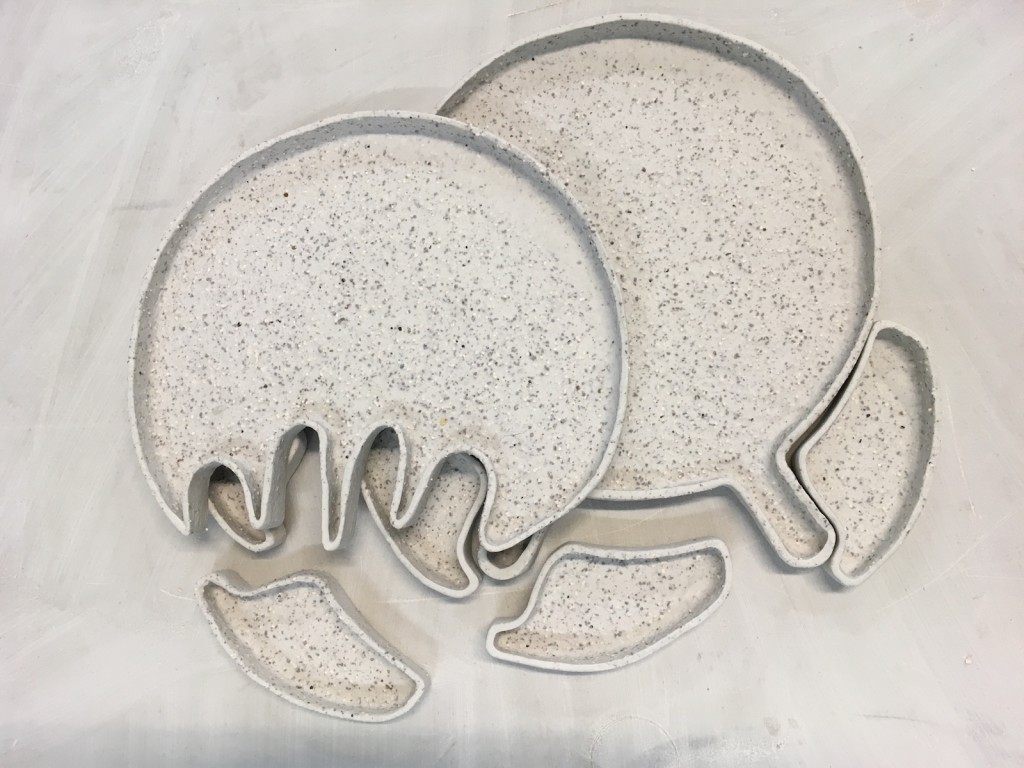

The result of these experiments will be on display this April at Ventura Future, under the name Remake Ceramics: Future History —a nod to both the origin of the materials and the hope currently placed on circular production processes.

This isn’t the first time that de Leeuw, the founder of Fabrique Publique, has used dinnerware to speak of environmental consciousness: a previous project, called Food for Thought, featured a bowl with a Netherlands-shaped protuberance, which nearly disappeared when the container was filled with soup. Potato soup, the North Sea in the near future, same thing.

With this project, she wants consumers to understand the value of what they discard. “Once we break a plate, a mug or a cup, we throw it in the waste bin,” de Leeuw recalls. “So it is clear that we cannot go on producing the way we are producing today, or we will create mountains of waste, losing tonnes of valuable materials.”

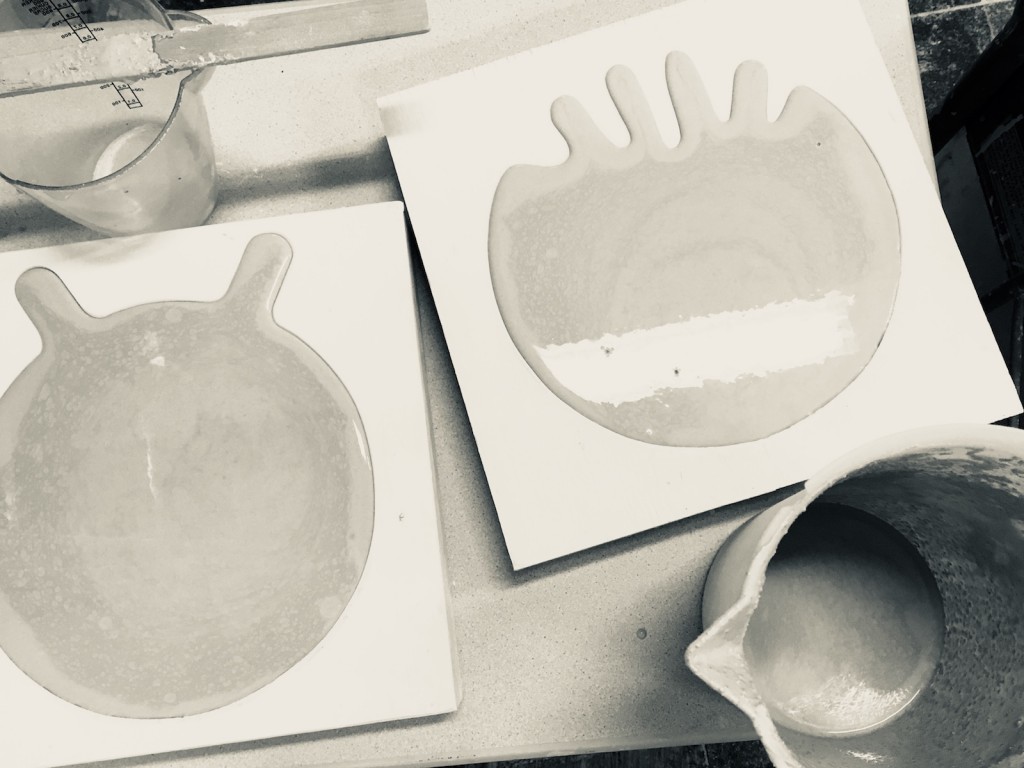

Surely, she thought, someone else must agree with her. After exploring production methods on-site in Arita and Gifu, in Japan, she found an answer: a few key factories had been mixing clay with up to 50 percent recycled waste. And much like China and Delft a few centuries earlier, she’s looking for ways to adapt pottery and create anew —coincidentally, the Resources and Recycling Lab at the Delft Technical University is where she grinds the pieces for her experiments. So far, she’s managed to insert 10 percent of discarded black stoneware, porcelain, terracotta, white earthenware and re-clay into a mix of liquid clay —the preferred state of the material in the Netherlands, versus its solid counterpart in Japan. Another difference? While the Japanese prefer a polished look that conceals the origin of the pieces used, de Leeuw wants the rough bits to act as an explicit, visual and tactile reminder. “I want people to see and touch these plates and be aware of where they came from and why they are like this.”

That first round of production will be available to see and touch this April at the FutureDome, one of the new divisions of the Fuorisalone platform formerly known as Ventura Lambrate. “[But] the aim is to undertake further research to stretch the boundaries of how much recycled material can be added.” Luckily, with Cor Unum’s attitude towards experimentation, those boundaries will certainly be stretched.