Interview with Stefano Boeri and Jean Blanchaert

As their exhibition, Next of Europe, part of the 2022 Venice edition of Homo Faber was getting underway, Stefano Boeri and Jean Blanchaert spoke with TLmag about their vision on craft and the importance of supporting master artisans around the world.

As an architect, Stefano Boeri believes it is his ‘mistakes’ or imperfections which make his work richer and more complex. “Hands and manual work are so important. I am interested in how imperfection can be, could be, should be a value. If we simply trust robots and machines, then we will never have this complex anima… there’s a soul that comes from imperfection.”

Craftmanship, he believes, calls for empathy and the ability to listen. It involves the same attention we devote to a conversation and yet, for many, it has long been lesser valued in comparison to the spheres of art and design. No longer if the juggernaut of the second, three week long Homo Faber exhibition, which landed on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice this April at the Foundation Giorgio Cini, is anything to go by. Celebrating contemporary craft, the 15 exhibition spaces and work of some 400 artisans and designers from more than 40 countries (with a particular focus this year on Japan), tells of people who have been able to make the most of awareness and listening. Within the context of large-scale manufacturing, craftsmanship has become a way to foster lasting ties between distant cultures and countries, it is a link with our roots.

Boeri, who is also president of the Milan Triennale and a professor at the Politecnico University in Milan, co-curated the ‘Next of Europe’ exhibition with the Milanese gallerist, Jean Blanchaert. The pair, who met as children growing up in the same apartment block in Milan, also co-curated the exhibition, ‘The River of Europe’, for the first Homo Faber event four years ago.

How did Blanchaert, who is also an antiquarian, glass sculptor and illustrator, decide on his selection? Eyes alert and slipping into a broad smile he tells me his criteria was for contemporary craft masterpieces. “Contemporary – meaning that if you make a magnificent piece but that reflects the past – then that is not what I am interested in. Similarly, craftsmen who work on their own without any help…. I want to see the collaboration of a school, an atelier, a lab, not the product of a soloist”.

“The aim of the exhibition ‘Next of Europe’ was to reward those master artisans who teach an apprentice or a curious person, the secret of their craft. Whilst the World Wildlife Fund seeks to slow the natural degradation of the planet by saving forests and pandas, the Michelangelo Foundation, which supports Homo Faber, opposes cultural degradation and encourages the revival of a more humane way of life.”

Blanchaert reminds me that master craftsmen do not work looking at the clock: “When we purchase a handmade object, we come into contact not only with the personal history of the masters who made it but their homeland, the collective cultural heritage. It is like expressing the core of where a wine or cheese is made. Or when you speak a language, you have an accent.”

From Paris, William Amor upcycles plastic waste to create delicate floral works, each one imbued with his philosophy that plastic waste is a raw material with creative potential that can be transformed into beautiful objects which carry a strong message.

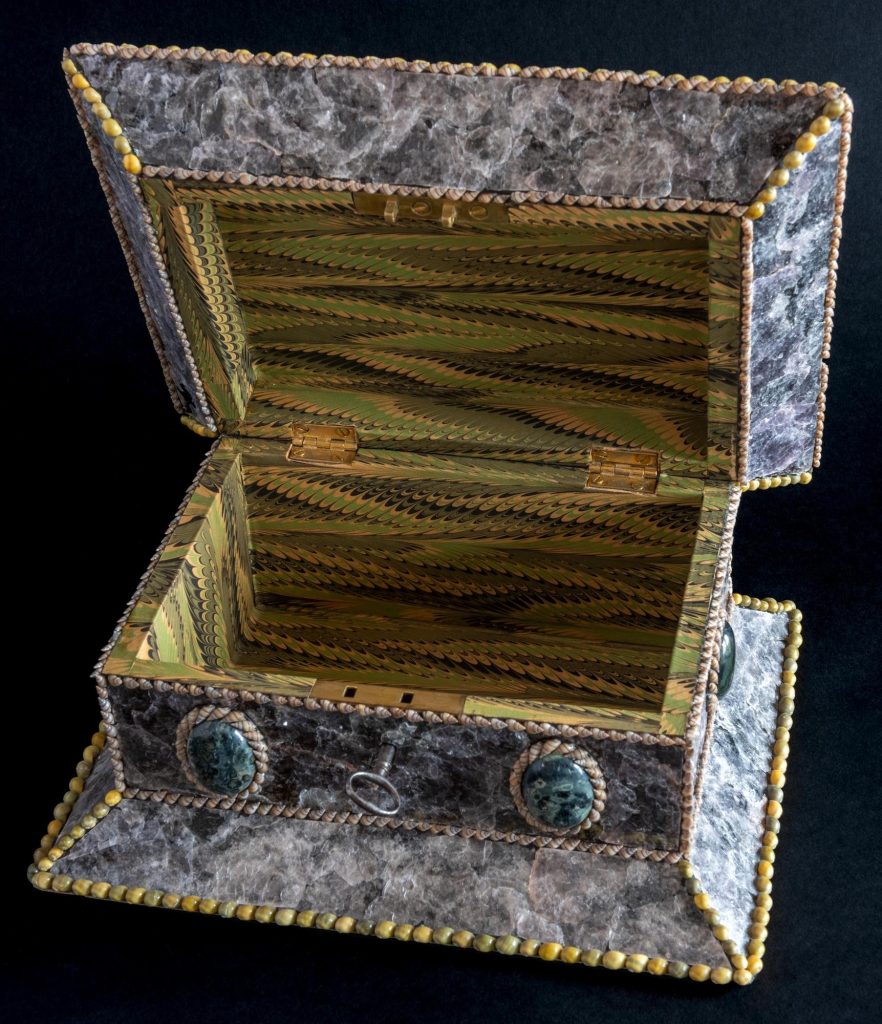

Tess Morley, a British designer, creates grotto style lamps, ornate mirrors and caskets using shells that she has collected from British shores. While Danish artist, Steen Ipsen’s white glazed earthenware balls are fired several times to obtain a perfect, monochrome surface. In contrast, the red strings express the influence of the sculpture’s movements and contribute to a strong graphic expression.

The ceramic piece by Bela Silva is a fusion of fine and applied arts. Passionate about both ceramics and drawing, she was originally told she had to choose one medium but decided to listen to her gut instead, and now works with both.

Kristina Riska is considered to be one of Scandinavia’s foremost contemporary ceramic artists. Her work starts on paper, yet the design takes shape as she works in clay and there is a powerful serenity in her work, energy that emulates from the undulating, fluid curves and organic palette of glazes.

“The aim of our project was to shine a light on the oscillation between the aesthetic dimension and the productive functionality of a project. It’s what makes the Jean Blanchaert and Homo Faber perspectives on design and craft so unique in today’s cultural context” explains Boeri.

Do they think that the artists felt the pull of the recent pandemic and the war in Ukraine? “Well I think the pandemic throws up a sense of uncertainty,” reflects Boeri, “and so we have an awareness of that dimension and can work on it. It’s a positive condition though, whereas the war is exactly the opposite. It’s about rigidity and cruelty. During the pandemic we were suffering yet all together, whereas the war is isolating. What I’ve noticed are themes of flexibility. There is also an uptake in recycling materials and of course the concern about plastic: how can you make it, recycle it, also not use it.”

As to whether A.I is always the huge threat it is portrayed to be, Boeri is emphatic on its benefits and the need to follow it and explore it. “Why not? It can be good or bad but it can be supportive too. To give you a very simple example, imagine this room as a Metaverse experience. Now of course, you will never substitute what you are seeing or feeling right now, this very moment in time, but it could be incredibly intriguing as an additional experience.”

The journey that sticks in Blanchaert’s mind most was ‘truffle-nosing’ in Albania. “When I go somewhere, I don’t contact the local craft council or official guides, I like to,” he says tapping on his nose, a touch theatrically, “dig around. I’d lost my luggage in Tirana airport and while waiting I got talking to someone and I explained why I was there. He immediately told me I had to go and find the sculptor, Andrian Melka. So I went there, and ‘there’, by the way, was a 5 hour journey in a car, and when I arrived, there was someone jumping in the river with an eagle on his shoulder taking enormous stones and breaking them up. Very much in the Michelangelo way, he attacked them with a hammer and his sculptures were very beautiful. It’s something that I will never forget seeing.”

For Boeri, the piece which is the most poignant is something I do not recall seeing. He walks over to the empty shelf and shows me the caption. The following words are printed below: “Here you should have admired the work of Ukranian artisan, Rustem Skybin. The outbreak of war in Ukraine made it impossible to transport his work to Venice. Michelangelo Foundation has decided to leave this space empty so it can be filled with thoughts.”

www.homofaber.com

@homofaber

www.michelangelofoundation.org

www.stefanoboeriarchtetti.net

@stefanoboeriarchetti