Jörg Bräuer: Capri Lithologie MMXXII

Jörg Bräuer’s solo show, “Lithologie”, has opened at Spazio Nobile in Brussels. He spoke recently with Marcia Bjornerud, Professor of Geosciences at Lawrence University in Wisconsin and author of the bestseller book “Timefullness”, about his recent body of photographic work, Capri Lithologie MMXXII.

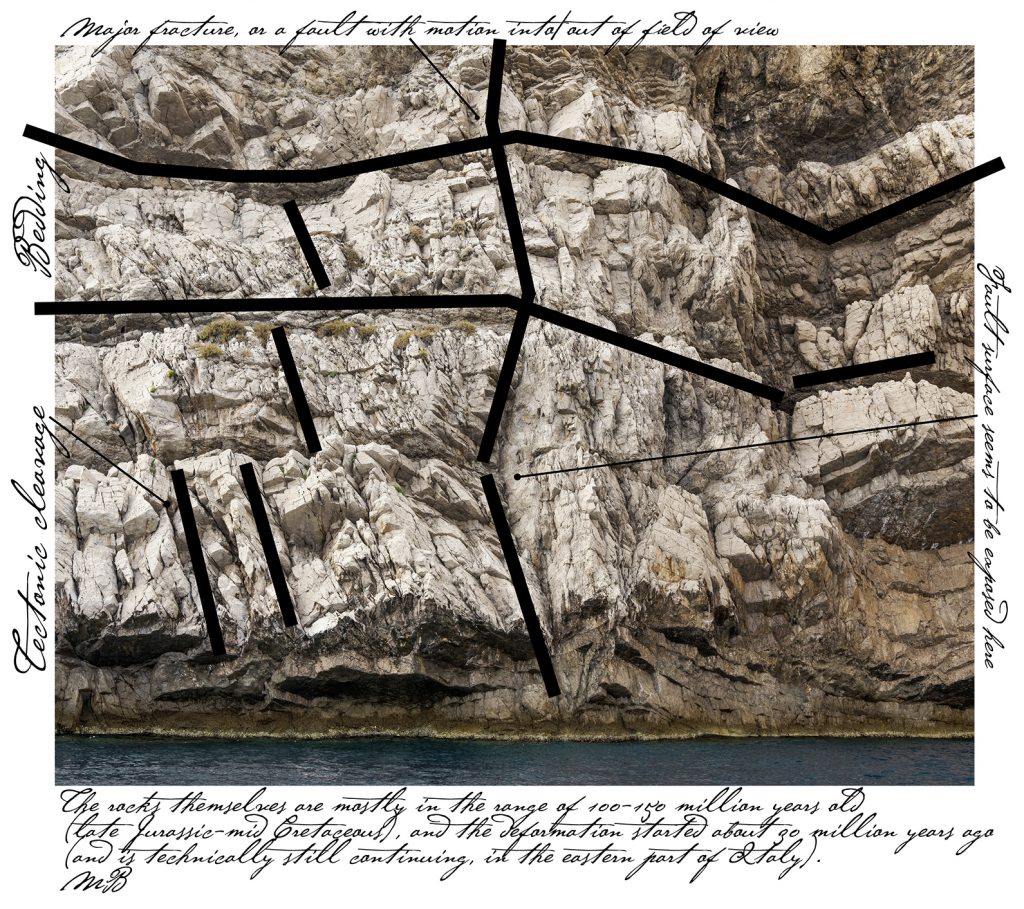

Over one hundred million years have shaped these limestone sediments of Capri; they hold memories of sea life before a great mass extinction at the end of Cretaceous era changed the earth forever; all forming part of the geological cycle that moves with the force of slowness. Earth time is far from my reality; I am made to live with the immediacy of my temporality. There is still time… I stop and observe the breath-taking beauty that these rocks of Capri unfold before me. The emergence of the cliffs is of such diversity, something beyond all human capacity. The aesthetic is orchestrated with the profound experience of a master and signed with a single name: the earth. Like in an open-air art gallery, I admire the abstract performances, there is no beginning or end, forming the inexhaustible source of my inspiration. These rocks invite me to rethink my position and my awareness in the face of time and earth. –Jörg Bräuer

Jörg Bräuer spoke with Marcia Bjornerud, Professor of Geosciences at Lawrence University in Wisconsin, about his recent body of work, Capri Lithologie and the knowledge that rocks hold about life on earth – past, present and future. The following is an extract from their conversation. The full story will appear in A/W 2022: TLmag38: Origine/Origin.

Jörg Bräuer: You take a picture — it’s a fragment — and it becomes interesting once you start to see the consequences after some time, and you begin to understand the language of the cliffs and rocks and this is what I am looking for in this new project.

Marcia Bjornerud: That captures one of the great challenges in geology — moving not only in time, but between the micro and the macro constantly — traversing different scales and holding them simultaneously in the mind’s eye and understanding how they relate to each other. As a teacher of geoscience, I realise that this is a very difficult and conceptual practice to be able to move between these different scales, and I think your photographs embody that.

J.B.: I think the photographs make it visually attractive and are like a door to enter into or something that you can hold onto; on the other hand, I am always drawn to the abstract part of the rocks — of what I don’t understand. I am being guided by my intuition and by the light, which communicates or makes the link for me to approach the rocks and their sedimentary elements and layers.

M.B.: You asked about rocks transmit- ting energies and maybe messages to us, and in my view, rocks have all the metaphors, all the templates, all the les- sons we could possibly need to live on earth. This idea that somehow we have outgrown this solid earth or that its inert and uncommunicative is a big part of our problem as modern human beings; every- thing we need is embodied in rocks if we just learn to see them as communicative and animate things. And they have many meanings and just like when things are in different lights and convey different moods, rocks can tell us different things depending on how receptive we are to what they have to say.

So, the limestones that we are looking at in your photographs, they have the story of being formed by tiny, microscopic organisms slowly accumulating, each one of those organisms having its own life, but then in aggregate they form these great carbonate banks that are the world’s carbon dioxide sequestration strategy. That limestones are the way that the earth, over long timescales, has put away car- bon dioxide that volcanoes have exhaled. If we didn’t have limestones we would be a greenhouse planet like Venus. These organisms collectively, in their death, I suppose, are doing an immense ecosystem service for all subsequent creatures on earth. And to me, every person on earth should give a word of gratitude each night for limestones and dolostones, for keeping the earth habitable.

J.B.: Maybe we should carry one around with us. Maybe we are losing the perception of the importance of them. I think people are not aware.

M.B.: I know, it is astonishing. And most limestones are biogenic, so it’s not just a mineral process it’s a biological one. And then, a really strange thing, this is a bit technical, but most of Italy, including Capri, was a continental shelf off the coast of Africa in an area referred to as Adria, like the Adriatic Sea. Adria was a great, shallow continental shelf, and the amazing thing about continental shelves is that they are liminal worlds, neither fully continental nor fully oceanic. Continental shelves are submarine, so they are not subject to erosion like the exposed continents, and over time they accumulate the sediments eroded from the continents. They are this strange hybrid, where the sedimentary archives of time can be preserved — vulnerable neither to erosion nor subduction. Even more remarkably, continental shelf sediments are commonly shoved above sea level after they have formed by tectonic upheavals — as in Capri and the rest of Italy — where we land-dwelling creatures can then read those archives. That is a weird and elaborate system, almost suggesting that the earth wants its story to be read!

Season XXIV – Jörg Bräuer, Solo Show, Lithologie, Spazio Nobile Gallery, Bruxelles, 18.11.2022–29.1.2023

www.jorgbrauer.com

@jorgbrauer

www.spazionobile.com

@spazionobilegallery